It was about this time, 37 years ago, I got into trouble for dragging a bag of sugar out the cupboard and into my school bag.

The cause was noble: some guy called Bob told us on telly to bring food in for the poor, starving children of Ethiopia.

I was in primary one, I lived in a council house and the year was 1985.

Five-year-old me didn’t have a relationship with the P-word, except for spitting out a line from In the Bleak Midwinter. No, poverty – or being poor – was something reserved for others in far, far away places.

Poverty was never far away from home

It’s funny now that I look back, because I grew up in a bit of Scotland which, by all accounts, was in the eye of the perfect poverty storm.

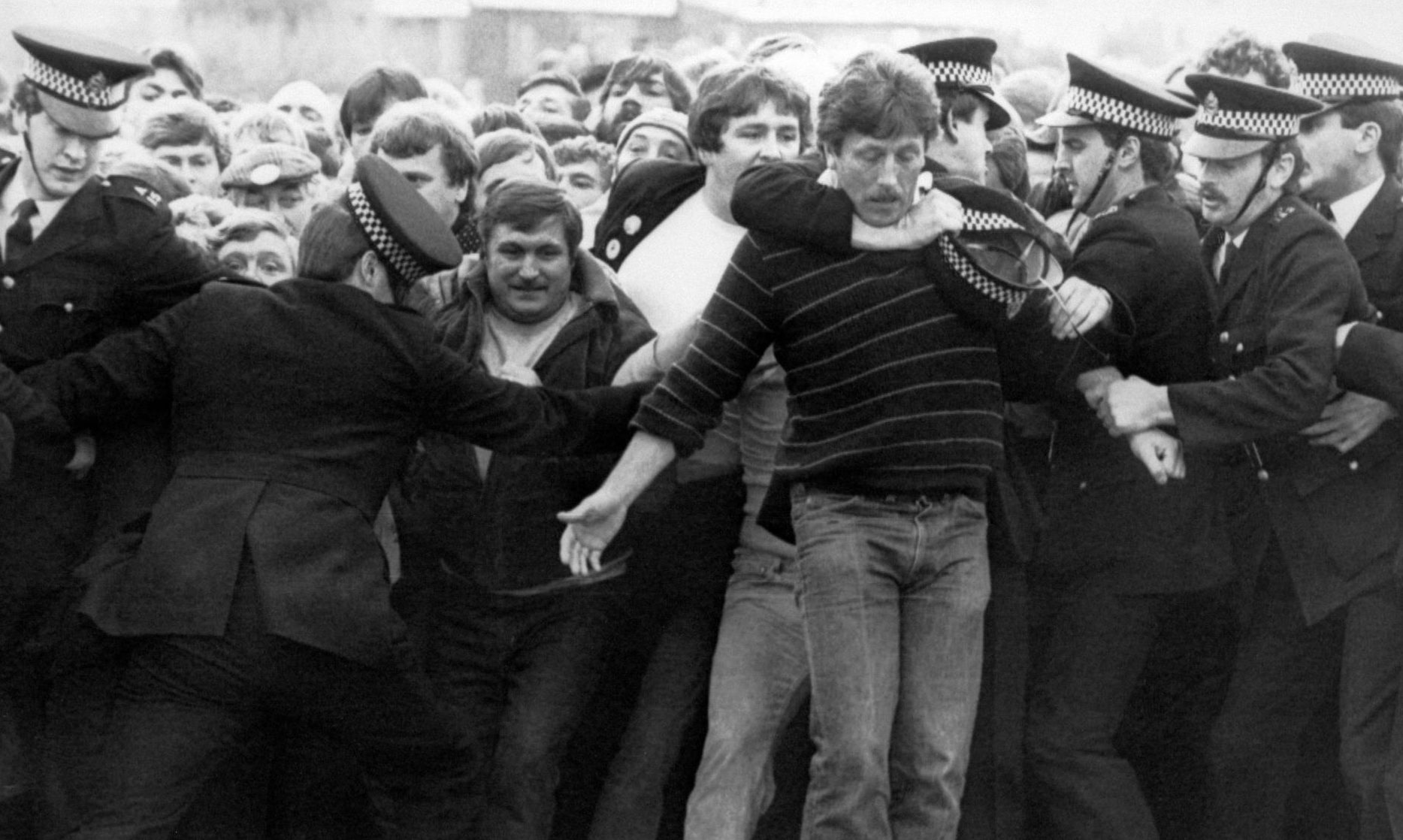

My uncles had been on strike at the pits while the threat of the steel works closing loomed like a dark cloud for everyone else. The wives of the miners in my village worked in factories making jeans.

As people were being arrested for poll tax violations, their jobs would begin to be worn down just like the knees of the expensive denim they were sewing.

I even remember my gran stopping going to bingo. In what we’d later call the “welfare”, women playing “housie” had to move over for a soup kitchen to be opened.

And I didn’t know anybody who wasn’t entitled to free school dinners.

Poverty wasn’t that far from home then. And it isn’t so far away now, either.

Heartbreaking injustice

I left journalism for a while, for a role in the charity sector. I worked for an organisation setting people free from poverty, addiction and sexual exploitation.

I had spent the years previous covering stories of human trafficking and child sex exploitation for a daily regional newspaper. Suddenly, I was able to meet the people I had written about.

It’s tempting to believe such things don’t happen here. Except, they do

For that charity, I travelled to Kenya. I sat with women on death row, with a cooperative of HIV positive women and with women living in slums.

One day, in a school playground, I heard a story of a girl who had been “violated”. She had been sold by her mother to men in the dark nighttime slum streets, in exchange for food.

I assumed it would be one of the older girls; some 16-year-olds were gathered, giggling in front of me.

I was wrong. The child in question was five years old.

My heart couldn’t cope with this level of injustice and pain. She was pointed out to me and, like a reflex, I scooped her up. The picture of us together shows me smiling, but it betrays a cacophony of other emotions.

We played and she laughed. And that wee lassie wet herself on my knee. She had been so brutalised, physically and emotionally, that her muscles didn’t have the strength to hold on – and her heart was too weak to process positive affection.

I had to be careful not to box those experiences off as being representative of a different kind of poverty. The far away kind.

Because it’s tempting to believe such things don’t happen here. Except, they do.

Left with no choice

What I’ve come to learn is that poverty is not simply about a lack of stuff. It’s about a lack of choice.

In Mumbai, I worked with a charity that educated slum children in buses and set up culinary schools. Why? Because when girls in particular get to a certain age, there are so few choices that prostitution can easily seem like the best option.

Education affords choices. And choices equal the possibility of a different path.

In Uganda, poverty of options looked like one mother selling food scraps to pay for her child’s education, leaving her unable to pick up and pay for her antiretroviral medication.

Her choice was this: do I provide a future for my child, or do I save myself?

Here in the UK, however, it’s much more subtle.

There are, of course, those dilemmas we have become much more familiar with – like heating or eating. Heart-wrenching choices that, in truth, we’re all only one step removed from.

It only takes one illness or another lockdown and job losses to mean we no longer have the means to live the life we once took for granted.

But there are other, more exploitative scenarios.

Every statistic tells us that poverty puts children and young people more at risk. More at risk of addiction, of falling into crime, of illiteracy and poor health. But also abuse.

It started with a free pizza

I’ll never forget the day I came face-to-face with a young woman I had written about previously.

Barnardo’s had told me about children being internally trafficked across county lines for the purposes of sexual exploitation.

All the while, I had been investigating gangs of men using takeaways and taxi businesses to groom young people.

A shocking but faceless case study was given. It detailed a court case involving a teenage girl who had been repeatedly taken to a different town and sexually assaulted by one man after other. When it went to court, she defended the man who organised the “party”.

Months later, I was introduced to her. Over a cup of tea, we chatted.

She had no money and when her friends were buying chips and cheese at the end of a night, she was left to one side. Already feeling low because she hadn’t been able to afford the entry to the club, she had waited in the bus stop.

An observant but much older man asked her where her boyfriend was. When she said she didn’t have one, he bombarded her with flattery and promises.

“If you were my girlfriend I would treat you right… I would buy you nice things. I would take you out…”

She left with a free pizza and came back the next night.

Passed around for a fiver

She was 13 when this began, and was red-flagged as being vulnerable for half a dozen reasons. All of which started with the fact that she grew up in a home where the electricity constantly “ran out”, and she avoided school because her clothes were never clean.

At the last party, the man ‘charged’ his ‘guests’ a packet of cigarettes each for time with this child

By 15, she believed that it was love that drove her “boyfriend” to “share her with his friends” so “they could see how lucky he was”.

When the police, social workers, family and teachers tried to remove this girl from the situation, her biggest fear was that she would lose the money and all the nice things.

At the last party, the man “charged” his “guests” a packet of cigarettes each for time with this child. She was given a fiver.

We can make a difference

As nefarious an example as this is, it’s not a one-off. Poverty is the basis from which exploitation thrives.

The unjust reality, though, is that none of it needs to happen at all.

There’s enough resource in the world to eradicate poverty, and there’s more than enough great people in our corner of Scotland to make a difference here. I’m both proud and excited that The Press and Journal and Evening Express have been able to partner with Cfine for our Big Christmas Food Appeal, to do just that.

It’s within our grasp to ease the pressure for families on our doorstep.

You can donate here.

Please, don’t discount the impact you can have; it can start with something as small as a bag of sugar.

Lindsay Bruce is a journalist, author and speaker