It was one of the rare occasions I walked out of the John Lewis store in Aberdeen with something I actually went in for.

For some reason, I usually came out empty-handed. We weren’t a perfect fit, so to speak.

It’s all water under the bridge now, after they abandoned their showpiece store in the city months ago, amid a public outcry.

But I managed to leave the other day with not one, but two things in my arms: a Moderna Covid booster in one, and a flu jab in the other. At last, I was a satisfied customer, exiting the cavernous old John Lewis building, which is now the city’s central vaccination hub.

It was strange to stand in a once-famous department store – a shadow of its former self. Stripped of dignity, I was reminded of a proud warship reduced to a sad old hulk.

There was a long, snaking queue like those in airport arrivals halls, but this was actually moving. Fairly brisk, as it happened, towards check-in desks for jab processing.

It was like a scene in a war or disaster movie where displaced persons shuffle around a kind of makeshift hospital in a converted building. Crafty profiteers were lurking around outside – I thought of this because I’d just filled up with diesel.

I sympathised with those accusing big fuel retailers of ripping us off at the pumps with exorbitant prices even though inflated wholesale costs had dropped. Why can’t the government penalise them with an equivalent amount to match the unfair profits they were supposedly making, and pass it onto the NHS?

There are always heroes and villains in every crisis.

Professionalism despite immense pressure

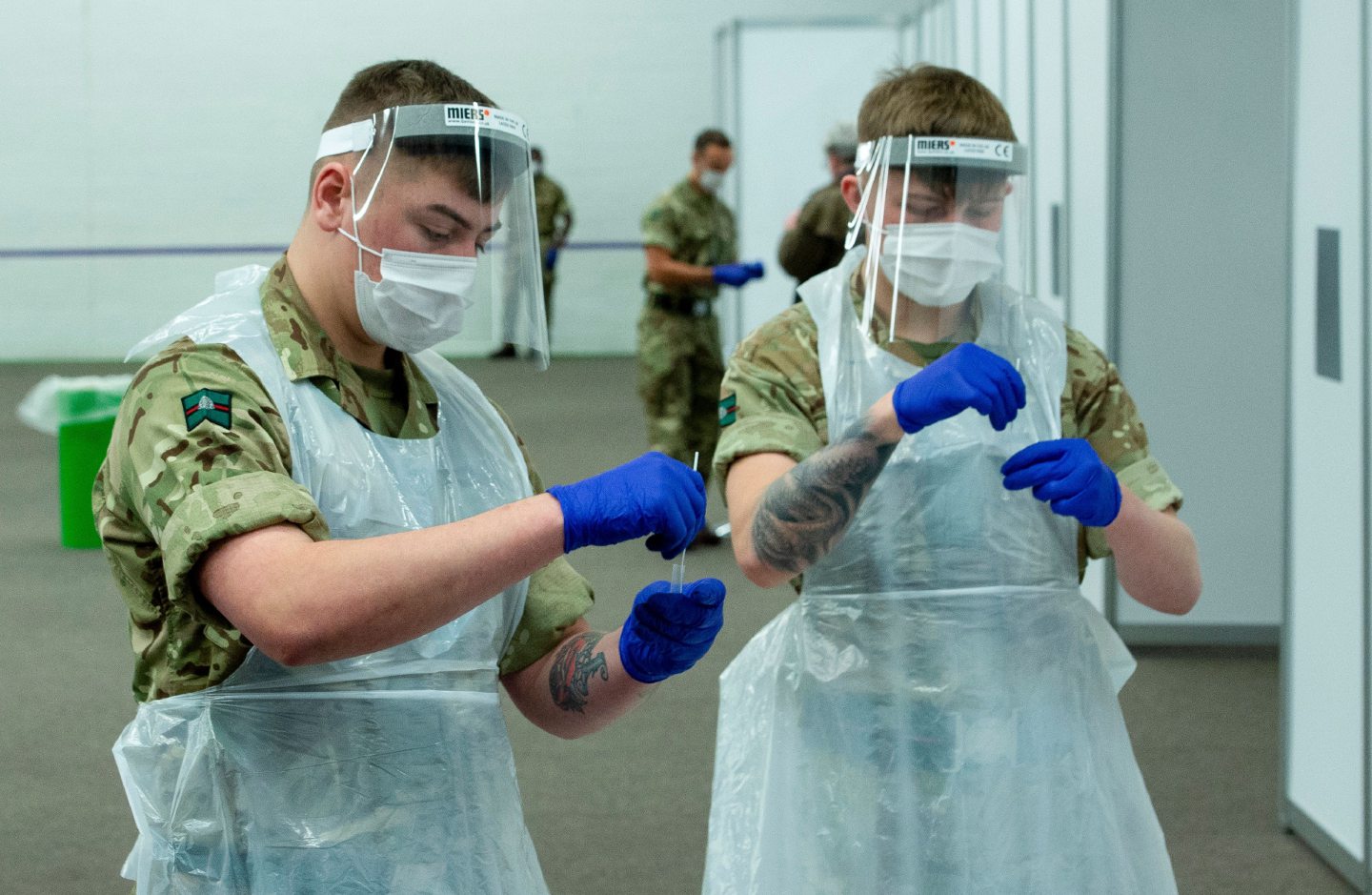

I could see some heroes now, as my wife and I moved onto a second queue heading for a vast jabbing zone, which stretched from one end of the building to the other. They were nurses from hospitals and GP surgeries around the north-east, joined by army personnel from military units all over the UK.

I was greeted at my jab station by a nurse in a corporal’s uniform who told me she was in Queen Alexandra’s Royal Army Nursing Corps. Normally based at a civilian hospital in Surrey to keep her skills sharp, she had been drafted to Aberdeen to help the locals.

She handed me over to another uniformed corporal to administer the jabs, but, to my surprise, he was not even a nurse. He was also from a base in England, sent in to support the crisis in Scotland, but I discovered by trade he was a forward observer in the Royal Horse Artillery.

State resources are creaking under the immense strain of the pandemic, but, despite being a fish out of water, I thought he did a very professional job

I won’t go into too much detail in case Mr Putin takes notes, but his job was hiding under the noses of the enemy and directing incoming shells from up to 20 miles away. Now, he was hunkered down somewhere between Hugo Boss suits and haberdashery in the old store; I know this because some of the former John Lewis signage was still visible.

He told me cheerily he had been given basic training to carry out injections. It just shows how state resources are creaking under the immense strain of the pandemic, but, despite being a fish out of water, I thought he did a very professional job under the circumstances.

Getting on with things seems the most sensible option

While hysteria intensifies over Omicron and the race to get everyone triple vaccinated – by force in some countries or persuasion here – old-fashioned British stoicism was in good supply in the Aberdeen booster queue. People just seemed to be getting on with it, for the simple reason that it was the most common sense thing to do.

It was as though they accepted Covid would fade in its dangerous potency one day and we would ride the storm, but regular boosters are now a way of life for the foreseeable future. So is “miserable dystopia”, as one Tory backbencher described tougher restrictions.

Maybe we were also boosted by news that Moderna as a third vaccine was shaping up as the strongest immunity provider in some research, but that was pre-Omicron.

I wish I paid more attention to those Scottish NHS adverts where people dress sensibly in loose short sleeves for their jabs. Unable to roll up my tight-fitting long sleeves, soldiers camouflaged me behind a screen to spare the public while I stripped off.

I felt impelled to tell them about my conspiracy theory that clothing manufacturers made large-size shirts tighter these days, so they don’t fit me. But I decided it wasn’t the right time or place.

David Knight is the long-serving former deputy editor of The Press and Journal