I remember hearing the Reverend Doctor George Whyte, now Church of Scotland principal clerk, preach at a Christmas watchnight service at our local church.

He spoke of “the Marks and Spencer’s Christmas” where everything in the overflowing, warm and hospitable household is perfect, blissful and charming. Of course, Christmas is not always like that in many households.

Many households experience something more like an Eastenders or Royle Family Christmas. Grief, trauma, tensions, worries and concerns can cloud out modern facades, as well as the true meaning, of Christmas. John Lewis TV ads have shone an important light in recent years on issues of loneliness and loss.

Christmas is always tinged with an element of sadness for me. Many years ago, I lost a close relative in a tragic and avoidable school accident, not long before December 25.

That year, it passed by as another long day with unforgiving minutes, as opposed to fun festivities. Christmases ever since still bring thoughts of those events.

People say grief is like a large rock inside you. Initially, that rock is heavy, with sharp, jagged edges. With time, the sharpness can reduce. However, the pain and memories are ever present.

The kind spirit of humanity can turn sadness to joy

I remember the first year I felt a return to festive normality. I had started teaching in one of the poorest areas of the county and was helping with their Christmas fair. It was essentially a jumble sale with other activities bolted on to make an inclusive community event in the school hall.

I recall my sadness at seeing the length of the queue to come into the sale that morning. Poverty is a dreadful thing. However, any initial sadness turned to joy as a true community festival ensued.

If it were not for the community-orientated staff arranging the fair, some children may have got few Christmas presents that year. Furthermore, a circular economy approach saw many good toys, games, CDs and books well reused again.

The spirit of Christmas, a spirit of humanity and a spirit of kindness to the environment all need rekindled. That year, previous difficult Christmas thoughts were overtaken by seeing the festive period’s true spirit captured by a community pulling together.

This year, I felt grief progress for me again. Whether it was down to a significant anniversary of my relative’s death, Covid sparking deeper reflections on life, or the opportunity to speak more about my family member’s death during 2021 and better consider tragedy, I am not quite sure.

Tragedy and trauma are terrible things. They affect every aspect of our life – work, household living, day-to-day life and major events

The 25th anniversary of my tragic loss allowed me to assemble my thoughts on the importance of loco parentis (taking legal responsibility for someone) as an educator, and how contributing members of civilised society can stand up for those more vulnerable and, thus, create community cohesion for all.

Leaders play a vital role in ensuring a caring culture permeates and lessons are learned in a mature, solution-orientated, improvement-focused way when things can, and do, go tragically wrong. Righting wrongs is a key Christmas message. Hogmanay also gives opportunities for vows and life changes.

Reconciliation is needed after traumatic events

Tragedy and trauma are terrible things. They affect every aspect of our life – work, household living, day-to-day life and major events.

As the world eventually moves forward from Covid, we must remember the trauma we have all suffered – be that direct loss, lack of human contact and interaction, or the mental impact of turbulence, worry and angst that the pandemic has caused.

Like the grief rock, hopefully the spikes of coronavirus and the sharp edge of its physical and mental impacts will wear off. It will take time and togetherness to overcome trauma. That will be different for every person. Some will bounce back, using adversity to propel great achievements. Others are stuck in a long, Covid-like rut.

Amidst it, we need to remember others around us are often fighting battles we cannot see. Those battles are bad enough when rational and “seen”.

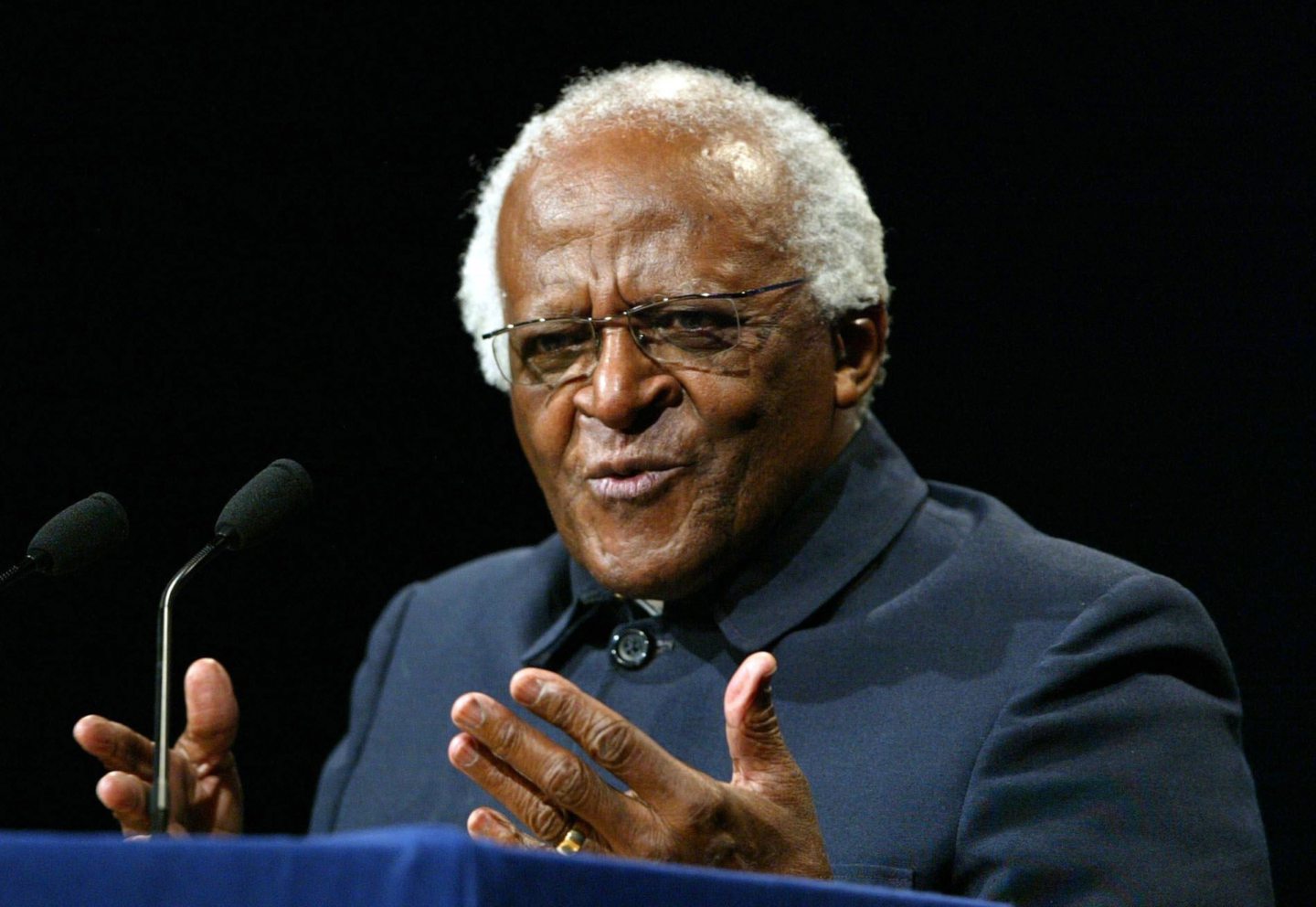

Trauma deliberately caused by perpetrators of wrongdoing requires a clear focus for justice and, indeed, reconciliation. Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s death has many thinking just now about reconciliation after traumatic events.

However, when the trauma’s cause cannot be seen or controlled, like Covid, overcoming it can be more challenging. The only thing we can control is our response, and trying not to react. Empathy, time and listening to others and ourselves can be important.

Like the school Christmas fair, how do we return to the true spirit of humanity and basis of civilisations – cooperation, kindness and togetherness – especially during a tragedy or trauma for those most vulnerable around us?

Neil McLennan writes in a personal capacity. He is a Burgess of Aberdeen and has supported every aspect of education in the north-east. His fee for this column will be donated to The Compassionate Friends, who support bereaved parents and their families