I was recording a podcast last week about Nicola Sturgeon’s new plan to secure independence.

The conversation took in the usual stuff – the opportunities, the risks, the legalities, the politics, the Unionist response.

I’d noted down in advance the points I wanted to make, but just as things were wrapping up I found myself going off script.

I admitted, rambling a bit, that I found the whole prospect of another referendum – either in traditional form or the “de facto” version suggested by the First Minister – to be a deeply depressing prospect.

Suddenly, 2014 didn’t seem so very long ago. Memories of the online and offline abuse, the division, the damage done to friendships, the general stress and anxiety of the time, flooded into my mind like an ominous, brooding oil slick.

I recalled how, in the week after the vote, I found my shoulders unclenching, not previously having realised they were clenched. But they had been, for months.

Scotland has important challenges

What, reader, was your response to Sturgeon’s announcement? I suspect the Yes voters among you were cock a hoop, instantly ready to march and chant and joyfully wag your saltire from side to side. What took her so long, eh? Fair play to you.

If you’re a No voter, not so much. I heard the word “exhausted” used by more than one Unionist friend. That too, but my overwhelming emotion was sadness – sadness that we will have to go through all that turmoil and confrontational extremism (on both sides) again, and so soon, and when there’s so much else to be getting on with.

From inflation to poverty to our horrendous drug statistics to a declining education system to a struggling economy, there’s no shortage of difficult but important challenges to which ministerial minds and energies might be applied, even within our existing constitutional arrangements.

Instead, we will spend the next few years shouting at each other about the nameplate on the door.

Politics is interested in you

Politics at its best offers the voter two routes through: it can lift the spirits to know that the right people are in charge and are working hard and effectively to make the world a better place; and it can be something that need not impinge too much on your daily life unless you want it to – they do their job and you do yours, and both do it well.

For most of us, though, neither of these options has been possible for some time. Since the financial crash of 2008 one norm after another has been shattered, and disruption has followed disruption.

The economy has never fully recovered from the crash. A rogues’ gallery has paraded through public life, from the wretched Nigel Farage to the unelectable Jeremy Corbyn to our current, historically bad Prime Minister. Referendums on independence and Brexit have divided society down the middle. Covid has infected every aspect of existence. Your heating bill, your weekly shop and your mortgage are now intensely political issues.

In short, you may not be interested in politics, but politics sure is interested in you.

Unhappiness is at an all time high

In last week’s Economist, the head of the polling firm Gallup wrote about the rise of unhappiness. Jon Clifton said his company has been tracking the global mood since 2006, and has watched unhappiness increase over the past 10 years to what is today a record high.

The Ukraine war, inflation and Covid have all played their part, he said, but also poverty, broken communities, hunger, loneliness and the scarcity of good work.

Some 19% of workers are completely miserable in their jobs. While the richest have grown a little happier, there has been a substantial drop in mood among the poorest.

Emotional unhappiness, or wellbeing inequality, matters as much as income inequality, said Clifton. “Life could hardly be better for one-fifth of the world, and for another fifth it could hardly be worse.”

Breaking up the UK would create uncertainty

Clearly some of these problems affect some countries more than others, but all affect Britain and Scotland to a greater or lesser extent.

The pandemic only exacerbated the loneliness epidemic in our fractured communities, good jobs and rewarding work are threatened by robotisation and the gig economy, and poverty is a very real threat for millions.

Neither is the future something we can look to with much optimism, whether that’s because of climate change or hostile geopolitics or the fact that there’s no guarantee our children’s quality of life will be better than – or even as good as – our own. A grim present and an uncertain future doesn’t seem much of a deal.

Sturgeon argues that independence will allow Scotland to tackle these and other challenges in a more focused and coherent way. But breaking up the UK would create new forms of chaos and uncertainty, as well as major economic difficulties.

There is little in the SNP’s performance over 15 years of government to suggest they have the skill or the guts to make much of a difference anyway. In the end, they want independence because they want independence: always have, always will. Still, at least it would make Nicola happy.

Arguably the biggest gamble Sturgeon's taking is to fight the next GE on the single issue of Scotland becoming independent – 'a de facto referendum'.

— Chris Deerin (@chrisdeerin) June 28, 2022

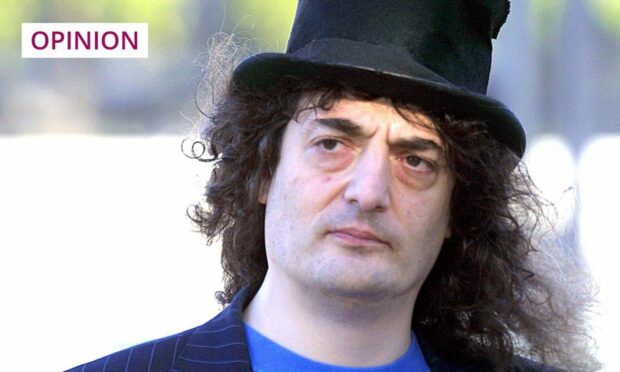

Chris Deerin is a leading journalist and commentator who heads independent, non-party think tank, Reform Scotland

Conversation