Child victims of human trafficking have been identified in Aberdeen.

Amid news of war, of heatwaves, of petrol price hikes and everything else we are grappling with post-pandemic, the most recent guidance report from Aberdeen city’s child protection committee references cases – plural – of child trafficking.

The document highlights just how complex such cases are to both identify and handle, but the facts are still screaming at me: kids have been moved here for the purposes of exploitation, using threats, force, fraud, or the abuse of a vulnerability. And it breaks my heart.

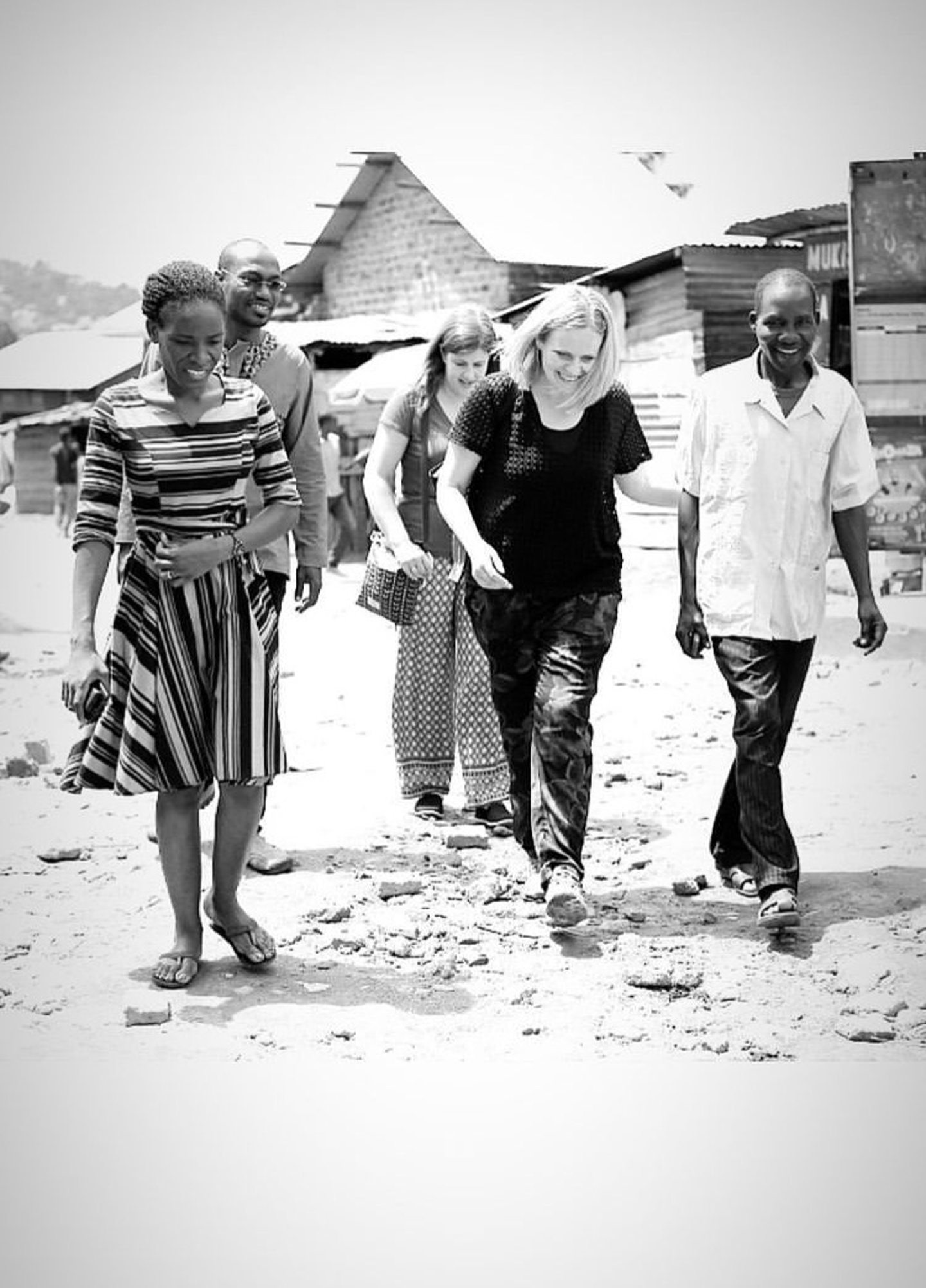

Let me take you back a few years. The place was Kibera, in Nairobi, Kenya. The five-year-old on my knee was a little girl sold by her mother on the lawless streets of one of the world’s largest slums. Poverty was the motivator, but a small child was the victim.

Every number is a person, every person has value. And human trafficking seeks to diminish that value, by reducing humans to a commodity to trade; as disposable means to nefarious ends.

The good news is that I appear to be living somewhere where such things are recognised, taken seriously and reported on. But, Scotland as a whole may not be quite there yet.

In a Scottish Government research report on child trafficking, the accuracy of how Scotland identifies and records these crimes was reviewed:

“It is apparent that referrals from Scotland are proportionately substantially lower than the UK as a whole. This raises questions about the accuracy of identification processes and actual numbers in Scotland…

“It also seems likely that Scotland is under-referring UK children as potential victims of trafficking compared with the rest of the UK.”

Without listening to victims so that the right support structures are put in place, and without people committed to finding and supporting those who’ve been exploited, human trafficking remains in darkness.

Children are not commodities

Due to the understandable need to protect their identities, I couldn’t obtain detailed information about the child victims of trafficking here in Aberdeen. But, when I asked about the numbers of children and the nature of the exploitation involved, the news was good and bad.

A council spokesperson said: “Our data in relation to trafficking locally indicates relatively small numbers arising in unique and various circumstances, involving children and young people of diverse sex and age.

I’m grateful this serious, organised crime has only impacted a few children that we know of

“We know that the reasons why children are trafficked are multi-factorial. This would include instances of children being exploited by others for criminal purposes as well as being sexually exploited.”

I’m grateful this serious, organised crime has only impacted a few children that we know of. But, I’ll say it again, children are not commodities that should be traded for the benefit of others.

The picture of exploitation

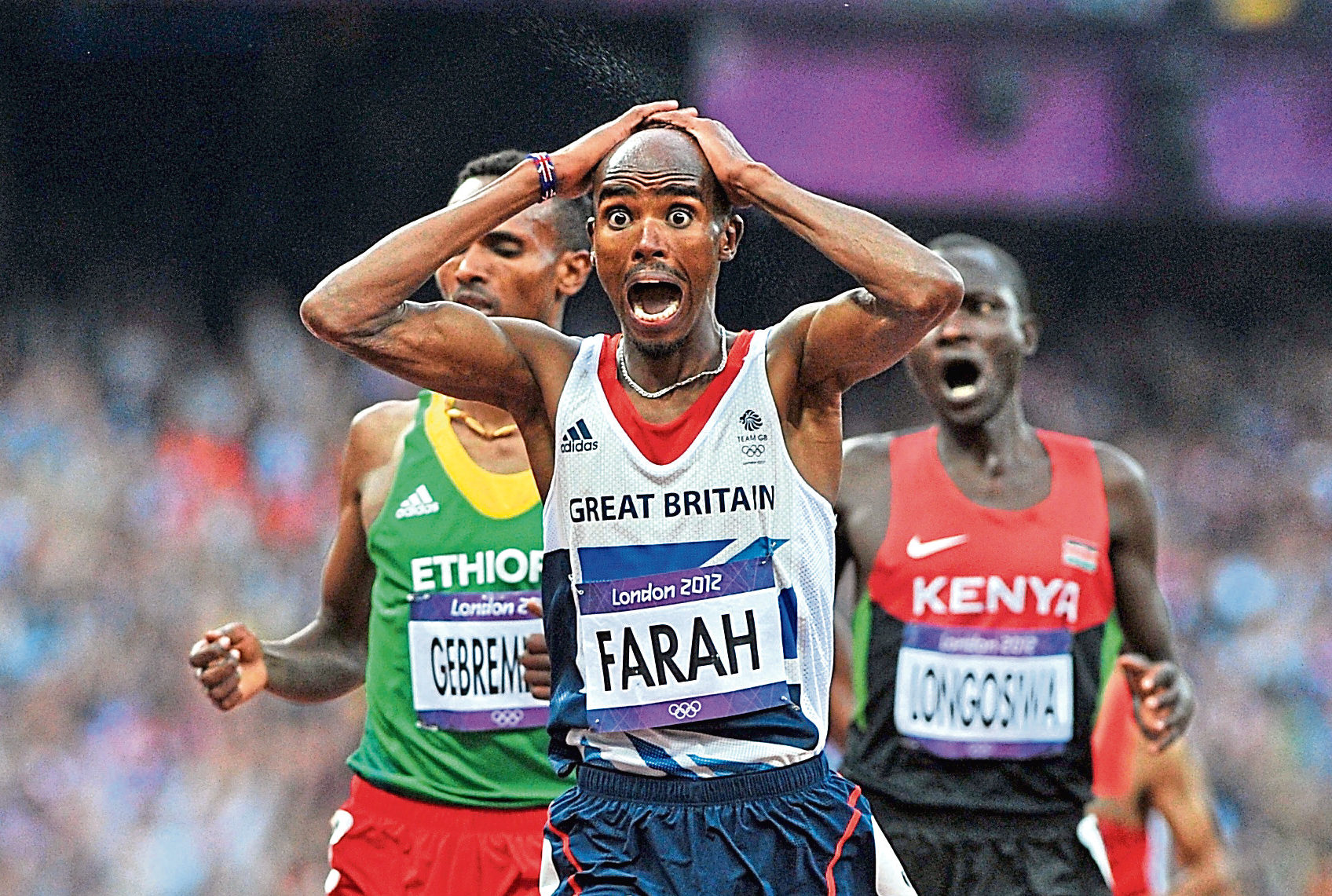

Did you catch the recent Mo Farah documentary? Telling the story of how he got from Africa to the UK, for the first time, Sir Mo – real name Hussein Abdi Kahin – explained that he was taken from his family, flown across international borders, and kept in a life of domestic servitude.

Warned not to tell anyone his real name, his abuse was hidden behind a veneer of “disruptive child” at school. Even a confession of what he had been through was all but ignored by social services.

Discussing his decision to speak now, the words “lying is a sin” were used. I could have wept. Isn’t it just the picture of exploitation – a victim carrying shame and guilt for that which was imposed upon him?

Let’s not forget that Mo’s story began in a country devastated by civil war. That’s a breeding ground for exploitation.

We can make a difference

Just this week, in a statement to the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), UK delegation Justin Addison echoed this warning.

He said: “The armed conflict in Ukraine, caused by the unprovoked invasion by Russia, has created an increased risk of human trafficking across Europe.

“The number of girls and vulnerable women who find themselves unaccompanied or separated creates significant risks of gender-based violence, and child protection and trafficking risks.

“Difficulties in accessing basic goods and services and lack of access to safe shelter have rendered women and girls extremely vulnerable to this form of exploitation.”

That awful statement of reality does bring with it some semblance of hope, however. If poverty remains a trigger, we can help eradicate that poverty.

Whether it’s by supporting things like the Big Food Appeal and local charities, or by helping break the cycle of poverty abroad, traffickers and those who seek to exploit others and prey on the needy can be disarmed.

As the old saying goes: “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good me to do nothing.”

Lindsay Bruce is obituaries writer for The Press and Journal, as well as an author and speaker

Conversation