Visiting Peterhead Prison Museum is an unforgettable and at times tough experience that emphasises the flaws in jail sentences, writes school pupil Lavinia Ismail.

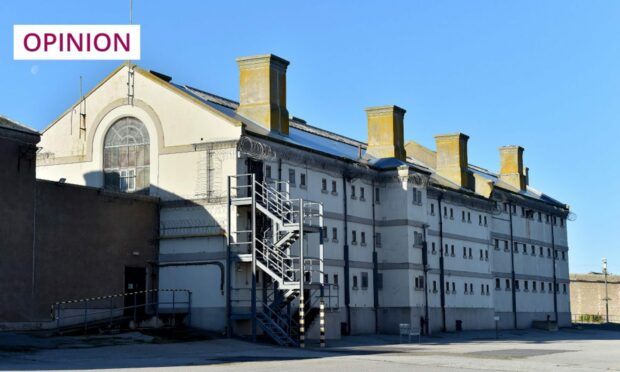

Peterhead Prison, known as “Scotland’s toughest prison”, was built in 1888, closed in 2013, and has been a museum since 2016.

Visiting was an extremely interesting experience, especially getting the chance to observe what a “genuine jail” looks like.

I had never visited a prison before, so I didn’t know what to expect. Well, maybe I expected a room with a bed, small windows, big halls, guards and so on. However, I got there and saw rooms with beds stained with blood, bars for windows, and strict, physically aggressive guards.

The museum kept the realistic stench of the prison – and let’s just say, I have never breathed through my mouth so much until that visit.

The prison’s notorious reputation is due to it once being home to the most violent criminals in the country, such as the serial killer Peter Tobin

Another infamous inmate was Johnny Ramensky. In 1934, he used his skills to trick the prison’s guards and escape, becoming the first man to do so from Peterhead.

However, his escape was short-lived and, once returned, he was placed in solitary confinement and shackled. As time passed, he tried to break out on four more occasions: once in 1952, and three times in 1958.

There were many other points when Peterhead Prison had its security questioned. In 1987, a group of life-sentenced criminals took a prison guard named Jackie Stuart hostage, for five days.

His captors paraded him on one of the rooftop of the prison building, 90 feet above the ground, and beat him mercilessly. He was threatened with being burned alive, but an elite SAS force stormed the prison to take control of the situation.

It was my idea of hell

Riots were common at that time, and the prison was not a safe place. Convicts often overpowered guards. Windows were shattered, fires were set, and homemade weapons were used.

Even on a good day, with little sanitation in the cells, the prison was overcrowded and in poor condition.

Understanding more about the reality of Peterhead Prison has humbled me, and made me feel pity towards victims of miscarriages of justice who didn’t deserve to be there.

I can’t even imagine surviving there for a couple of days; it was my idea of hell.

Near the end of the tour, I visited the punishment room. There was one structure in it – a vertical, metallic frame. Prisoners were strapped to it and whipped by guards. No matter what the prisoner had done, this was one of their punishments.

Being locked up doesn’t address the problem

According to the museum’s audio tour, long prison sentences have little effect on crime. In fact, time spent in that hell-like space can increase a person’s likelihood of committing a crime, by exposing them to more criminals who might influence them.

In my opinion, which might not be popular (or realistic), I don’t think jail is the correct response to crime, or even a proper punishment. Instead, I think a rehabilitation centre would have the most benefit.

Peterhead Prison wasn’t a win for any side

Being locked up doesn’t address the problem; it doesn’t improve anything or anyone.

I do wonder if rehabilitation would still give a victim closure but, regardless, Peterhead Prison wasn’t a win for any side.

Seeing prisoners’ artwork made them more human

As I was almost finishing my prison tour, I suddenly came across a small, oasis-like corner, where the museum has showcased artwork made by prisoners during their confinement.

Seeing a handmade wooden motorcycle and dozens of amazing paintings of nature, as well as sculptures based on living creatures, made me realise that some prisoners could have been talented artists, had they not committed crimes.

Similarly, seeing the rooms, photographs, and diary entries of past prisoners really made me feel as if I knew them. An inmate’s table was covered in movie posters – movies I adore. That shared interest humanised these men for me.

The fact that Peterhead Prison didn’t close much earlier is still astonishing to me. All the riots and violence that happened there emphasise that we should never forget this place. One positive is that it may have changed the future of prisons for the better.

Lavinia Ismail is a form 4 pupil at the High School of Dundee. She regularly contributes to the school’s newsletter, The Columns

Conversation