When I visited my granny’s, there was always a pot of tea to welcome me.

The giant teapot would be filled to the brim with scalding hot water, tea leaves carefully spooned from a metal caddy. The pot would then be covered by a knitted tea cosy to keep the brew toasty warm. While we waited for the right time to pour, I would poke my fingers through the holes in the lace tablecloth in anticipation.

The tea would cascade into dainty porcelain cups on saucers, complete with teaspoons. Back then, tea-drinking was an adult pastime. I’d ask politely and get a cup, then enjoy the thrill of pouring way too much sugar in, before only taking a sip or two.

Nowadays, my tea ritual is a bit more perfunctory: a bag dunked unceremoniously into a mug with a dash of milk, twice daily.

In the past, when I worked in an office full of people, a tea break was the highlight of the day. It provided an excuse to leave your desk, decompress, and make sure all was right with the world.

A cup of hot, sweet tea has seen me through life’s best and worst times. Everything somehow feels better afterwards.

National Tea Day is held annually on April 21, and that date coincides with the late Queen’s birthday. It was created to celebrate everything to do with tea-drinking and the quintessential British afternoon tea. I know that in the UK we are fond of a cup of Rosie Lee but, culturally, I’m pretty sure China got there first, and should take some credit.

A storm in a teacup which rankles me slightly is the fact that the UK’s most popular blend, English breakfast, was created by a Scot called Robert Drysdale. He was one of three enterprising Scottish tea merchants who founded Brodie, Melrose, Drysdale & Co in 1867.

Queen Victoria sampled his Scottish breakfast tea blend during a stay at Balmoral, before taking a supply of it back down south, where it was promptly copied and renamed “English breakfast tea”.

Our first cuppa was poured in 1680

In the past, Scottish grocers were purveyors of tea, and they also became experts in blending flavours together to cater for their customers’ tastes. Those skills have since played an influential part in the story of whisky. Both James Chivas from Aberdeen and Johnnie Walker from Kilmarnock learned and mastered the craft of tea blending before moving on to whisky.

We Scots have long been a nation of tea drinkers: our first cuppa was poured in 1680 at Holyrood Palace by Mary of Modena, Duchess of York. She had acquired her fancy tea-drinking habit while living in the Netherlands.

It quickly became a fashionable drink, and was taxed, so enterprising traders – like John Nisbet from Eyemouth – used to run a lucrative sideline in smuggling tea leaves.

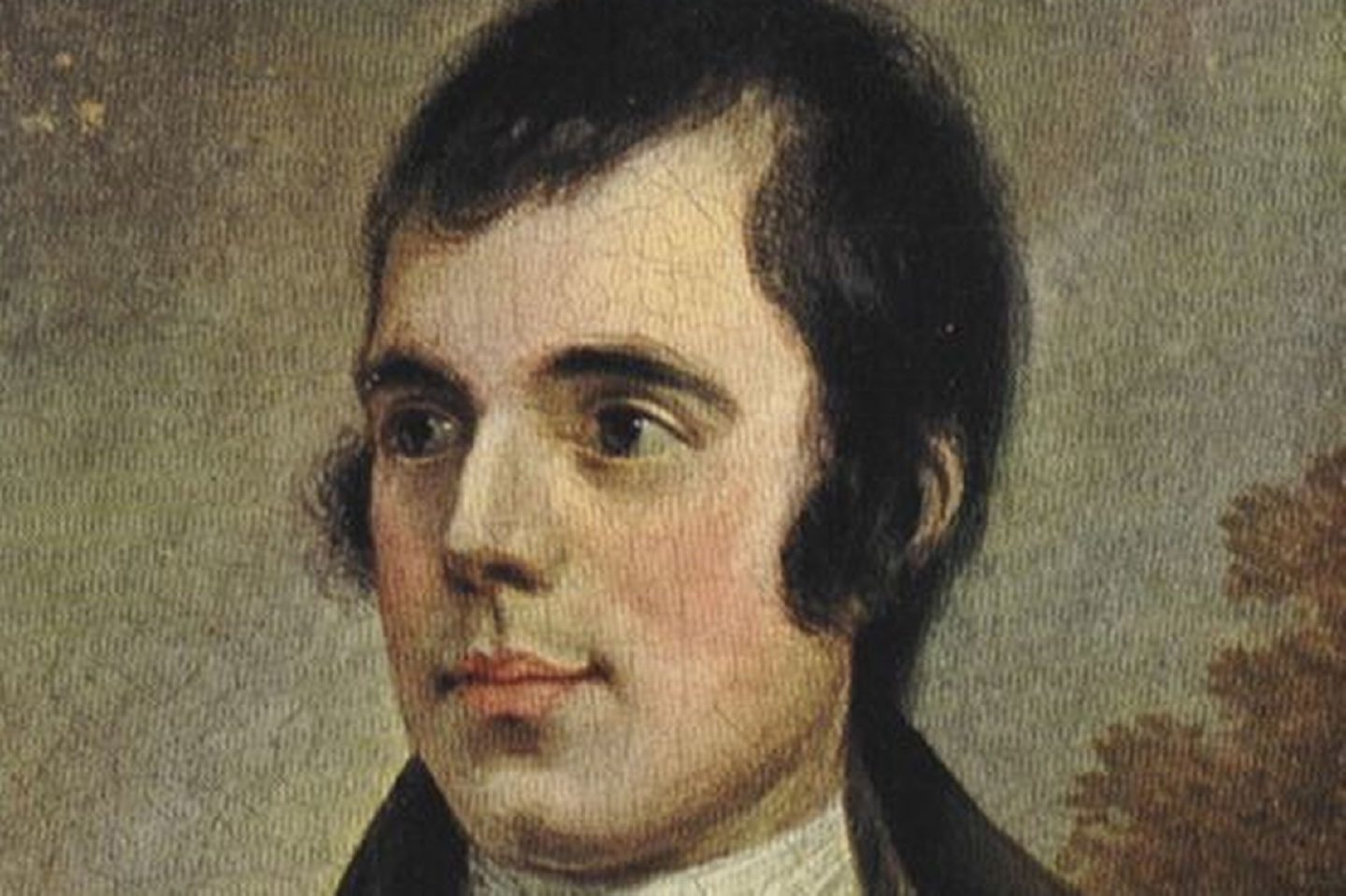

Even our very own bad boy poet, Rabbie Burns, was known to attend tea parties on occasion. At one in 1783, he met and fell in love with Agnes Maclehose, a married woman. Their unrequited relationship inspired the song, Ae Fond Kiss. Just think it, might never have been written if their eyes hadn’t met over that steamy brew.

Scotland’s long and complicated history with the tea trade

Scotland has a long connection with the tea trade, and not all of it is palatable. In the 19th century, merchants traded opium into China. Amongst the largest traders profiting from the misery of others were Scots, William Jardine and James Matheson.

It would appear that Scots have an uncanny knack for being in the thick of it. Robert Fortune was a plant hunter and spy for the East India Company. He collected specimens of Chinese tea plants to break the monopoly China had on tea-growing.

James Taylor established and developed the practice in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) with the help of another Scottish-born entrepreneur and tea merchant, Thomas Lipton.

In 1823, yet another Scot, Robert Bruce, discovered native tea trees had been growing in Assam all along. After his death, his brother, Charles Alexander Bruce, and David Scott are both credited with beginning tea cultivation properly in the Assam region.

The Scots still sticking the kettle on

Even today, the roots of the tea plant are found here. Charles Bruce’s great-great-great-granddaughter, Susie Walker-Munro, grows her own fine-grade Kinnettles Gold tea in Angus.

Susie also founded the Tea Gardens of Scotland, a collective of nine like-minded ladies across the entire country who have each established their tea gardens, growing plants from seeds rather than cuttings. Despite the weather, they have successfully produced a rare blend of Scottish artisan tea which is sold to discerning tea drinkers by Fortnum and Mason in London, under their brand, Nine Ladies Dancing.

In Orkney, Lynne Collinson has conquered the elements to grow the most northern-grown tea in the UK, on the island of Shapinsay. She has spent five years making her Norse Noir tea, which is 100% Orkney-grown. It is described as tasting light and bright, with notes of salted toffee and kelp.

So, come on, tea jennies out there, why don’t you stick the kettle on and join me with a nice cuppa, to celebrate a drink that is loved across the globe?

Catriona Thomson is a freelance food and drink writer

Conversation