Everyone loves a story. Here is one about a relationship.

In this story, one partner holds more power than the other. Their superior strength inclines them to arrogance: they control in subtle ways, resent challenge, and assume everything in the relationship is of their making and, therefore, under their ownership.

They take little interest in their partner’s history, because they don’t need to: their story dominates. The less powerful partner becomes angry and increasingly unfulfilled, taking every opportunity to vent their resentment. “See?” They say. “You have no respect!” Both partners lose.

This is not, as you might think, the tale of a marriage, a gender war, or even a personal friendship. It is the tale of the United Kingdom; the tale of England’s relationship with any one of the four home nations.

This week, historian David Olusoga, who has just completed a documentary series on the union, warned that the biggest risk to the UK’s internal relationships was not nationalism but indifference. Urging schools to teach the history of all four nations, he said: “Not knowing each other’s stories is a weakness we are one day going to have to address.”

Or not. But, whatever you think the political situation should be, what Olusoga highlights is that personal narratives matter, whether the relationship is between two individuals or two nations. The same skills that make small, intimate relationships like marriage work – communication, respect, equality of power, trust – are also central to making big public partnerships work. Looking at the headlines this week, it is clear that when one side ignores the narrative of the other, it affects the quality of the relationship.

Met Police perpetuate ‘one law for you, another for me’ story

Take the police and the public. Met firearms officers downed weapons this week because one of their colleagues was charged with the murder of Chris Kaba, an unarmed man shot dead by police in south London last September. The decision to charge the officer was made following investigations by the Independent Office for Police Conduct – the organisation designed to oversee police behaviour and protect the public – and the Crown Prosecution Service. It also follows criticism of armed police in the Casey report into Met Police culture, which also highlighted the “over-policing” of black citizens.

Most of us understand that mistakes happen when tensions are high and people fear for their own lives. We are humans, not robots. But Kaba was unarmed. In any case, do the police make allowances for circumstances behind the public’s behaviour? If someone dies because of dangerous driving, and the driver says: “I’m sorry. I was distracted because I lost my mother two days ago,” do they say: “No worries, mate. Let’s keep this between us”?

Responding to this issue, Met Police chief Sir Mark Rowley said: “Officers need sufficient legal protection to enable them to do their job and keep the public safe, and the confidence that it will be applied consistently and without fear or favour.” Well, exactly: without fear or favour. Instead, the subtext of Rowley’s comments – and his officers’ behaviour – is: we administer the law; we are not personally bound by it. Such power imbalances don’t work in any relationship: one law for you, another for me.

The underlying narrative in the Met’s relationship with the public is multiple scandals and broken trust. The relationship needs repaired by listening to the public’s story, not just the police’s. Arrogantly demanding forgiveness for past mistakes and unquestioning support for future judgments heals nothing.

Take away stories and people lose their identity

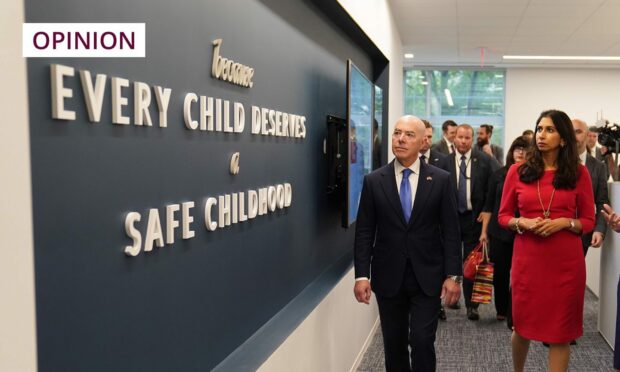

Here’s another one-sided story affecting public relationships: Home Secretary Suella Braverman’s contempt for international human rights law. Being gay or female, she declared, doesn’t make you an asylum seeker. Well, not if you live in Surrey. Try being female in Afghanistan, where you can be murdered for not wearing a veil, or gay in Iran, where the state can execute you for your sexual preferences. Take away stories and people – or countries – lose their identity. They become empty, political fodder. Olusoga hits the nail on the head: indifference kills intimacy.

In both private and public relationships, narratives matter. Who in Scotland didn’t raise their eyebrows this week over the Dennis the Menace advert encouraging business exports? “Created in London, unleashed in more than 100 countries,” the advert read, beside a picture of Dundee’s very own Dennis and Gnasher.

🤷♂️❤️🖤 Dennis the Menace was created here in Dundee, not London. pic.twitter.com/yMSVyaJpM8

— Andrew Batchelor FRSA 🏴 (@andybfaedundee) September 25, 2023

Dennis the Cockney Menace? What drove that? Ignorance? (Oops, I thought everything creative came from London.) Arrogance? (Stop quibbling – what’s yours is mine.) Disrespect? (I’ll exploit you for my own gain because I’m bigger than you.)

Countries need their stories heard, and so do people. The real story of Dennis the Menace? He’s actually of Italian stock: he grew out of a line from the chorus of an old music hall song: “I’m Dennis the Menace from Venice”. As for Gnasher, his heritage is African. He’s an Abyssinian wire-haired tripe hound. But they were born and bred, the two of them, in Dundee, Scotland. Let’s get this story – and this relationship – right.

Catherine Deveney is an award-winning investigative journalist, novelist and television presenter