Being told that you have Type 1 diabetes – in my case, as an Aberdonian teenager – is a life-changing event.

What I didn’t realise as a 15-year-old is that for those just a few generations before me, the same diagnosis was a death sentence.

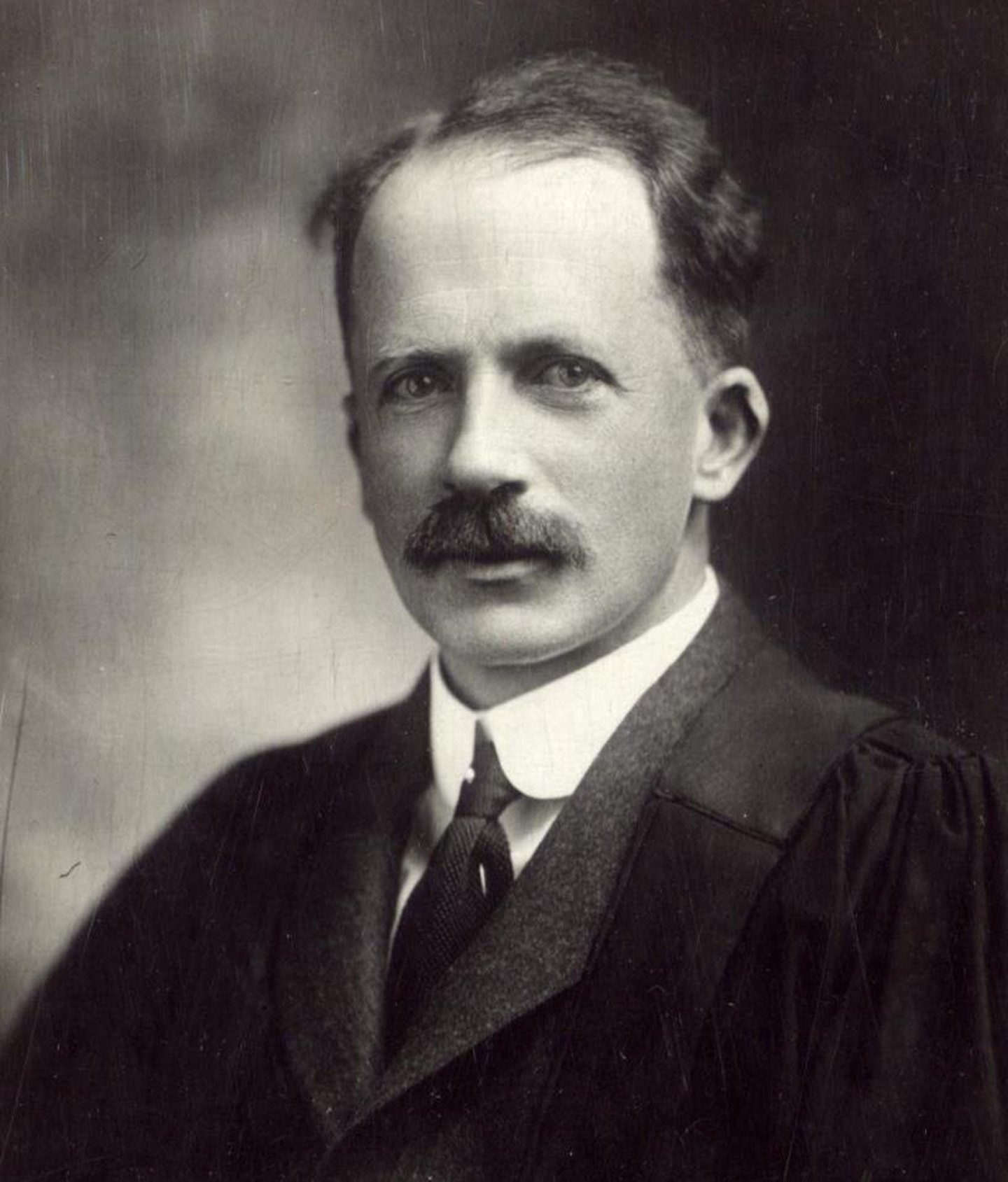

Work led by a University of Aberdeen graduate changed all that with the discovery of insulin in the early 1920s. But, for many years, the name JJR Macleod did not feature highly in the public consciousness, even here in the city where he was educated then taught and researched at the university for decades.

JJR Macleod’s educational journey mirrors my own. Like me, he attended Aberdeen Grammar School before becoming a student at the University of Aberdeen. His legacy is intertwined with my life and, yet, it took many years for me to fully understand the story of his career.

That story is of a man with a Nobel Prize, but whose contribution was questioned among infighting and falling-outs between researchers who worked on one of the greatest discoveries in medical science.

Later this week, the university will join in a wider programme of events designed to set that right, and which will coincide with the unveiling of a memorial in his honour at Duthie Park.

I have more reasons than most to be delighted by this development. Not only was my life saved by his research, I have followed his legacy through the classrooms and corridors of school and university, returning here as a staff member, just as he did.

Macleod’s 1923 Nobel Prize is now in the care of our Special Collections, and is a source of great pride to the university. But, during Macleod’s lifetime, it was tarnished by accusations that he had stolen ideas and claimed credit where it was not deserved. So much so that, at one stage, he was almost airbrushed out of the story of insulin discovery.

JJR Macleod’s reputation has been rightfully restored

Many of the most popular accounts of insulin attribute the feat to two Canadian researchers, Frederick Banting and Charles Best. They would later play down the roles of Macleod and the biochemist James Collip, with whom Macleod split his Nobel Prize money.

But, as with many things, modern scholarship has cast new light. The Canadian historian Michael Bliss returned to the original laboratory notes, contemporaneous papers and previously unknown sources to dispel the myths and restore Macleod’s reputation.

He noted Macleod’s vital contributions throughout the research, including giving crucial advice on how to prepare pancreatic extracts (later insulin), guiding Banting and Best’s work, bringing in biochemist Collip, and orchestrating successful clinical trials and physiological studies.

Bliss concluded that insulin emerged “as the result of a collaborative process, initiated by Banting, directed by Macleod, drawing on the great resources of the University of Toronto”. This account was immediately accepted in the diabetes and scientific world, and has not been challenged in the three decades his book has been in print.

Many challenges remain for those living with diabetes

This more balanced appraisal, recognising the importance of a collaborative approach and the need for world-class facilities, underpins Aberdeen research today, continuing in the footsteps of Macleod. This includes work to examine the causes of insulin resistance, how it can lead to Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, and research investigating different nutritional and pharmacological approaches to reverse or postpone these conditions.

Researchers at the university’s Aberdeen Cardiovascular and Diabetes Centre are also looking into innovative ways to detect, prevent and treat Type 2 diabetes. This includes testing new drugs and novel gene therapies, and using state-of-the-art single-cell genome sequencing and imaging methods. Scientists in the university’s Rowett Institute are studying how eating Scottish soft fruit such as raspberries, cherries and honeyberries could help prevent Type 2 diabetes.

The work of JJR Macleod deserves continued recognition for helping to save millions of lives around the world

Despite the remarkable advances made over the past century, many challenges remain for those of us living with diabetes. Improving this requires a multifaceted approach, bringing together researchers, educators, clinicians, health policy experts and healthcare providers to drive forward new treatments and preventions.

The University of Aberdeen will continue to play its part in the story of the treatment of diabetes and the alleviation of its consequences. The work of JJR Macleod deserves continued recognition for helping to save millions of lives around the world.

- Booking for the free event Celebrating 100 Years of the Discovery of Insulin with world-recognised diabetes expert Professor C Ronald Kahn on October 11 is now open via the University of Aberdeen website

Professor George Boyne is principal and vice-chancellor of the University of Aberdeen