The coming year promises to be a highly significant one at Holyrood, as MSPs grapple with new “assisted dying” legislation.

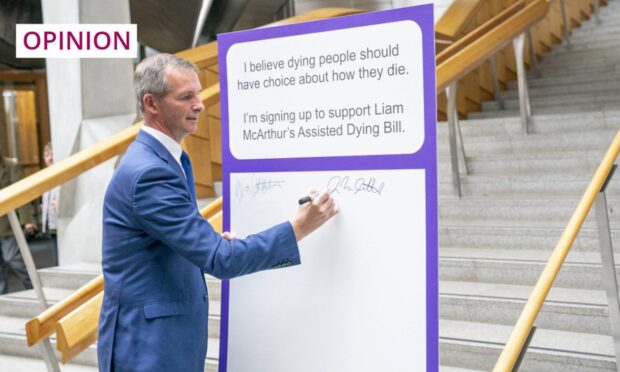

A member’s bill from Lib Dem MSP Liam McArthur, expected any week now, seeks to allow terminally ill Scots who meet certain criteria to access lethal drugs. Proponents say a change in the law is needed to give dying people “choice”, whilst opponents warn it would open up vulnerable groups to acute dangers.

This debate is often framed in the media as a standoff between “secular”, “progressive” supporters and “religious”, “conservative” opponents. It is, in truth, far more complex than this narrative suggests.

Moral claims are made by people on both sides. And many atheists, Humanists, agnostics, and social progressives are opposed to a change in the law, for reasons rooted in their own worldviews. Some see assisted suicide itself as morally impermissible. Others don’t, but oppose it for different reasons.

It’s worth remembering that personal experience – perhaps of a loved one’s death – informs people’s positions on this issue. Political debates must, therefore, be conducted with sensitivity and civility. MSPs need to heed personal testimonies from people on both sides.

At the same time, they need to be prepared to ask tough, searching questions about what is proposed. Because the implications of “assisted dying” would be profound and far-reaching.

The case hasn’t been made for changing the law

As someone who has looked at this issue in some depth, I don’t believe the case has been made for a change in the law. Problems raised in past debates have not been resolved. It is not at all clear how abuses could be ruled out – as a tragic litany of stories from other countries demonstrates.

We are talking here about very unwell, perhaps fearful people being given a cocktail of harmful drugs in a dose that is calculated to kill them. Permitting this would fundamentally change society’s response to suicide, and the doctor-patient relationship. It would also usher in profound new dangers for terminally ill Scots, who’d be susceptible to pressure.

Pressure to die could be overt – a person or persons subtly encouraging an individual to end their life. People would also, inevitably, feel compelled to choose “assisted death” for fear of being a burden on others, or because of difficult personal circumstances.

Disabled academic Dr Miro Griffiths, who previously wrote about this issue for The Press and Journal, argues that “assisted dying” does not involve “free choice”. He says: “We are talking about individuals who are living lives politically, economically, culturally, socially, where they are exposed to injustices, and those injustices will have a consequence on the way they value their life.”

Dr Griffiths is right. Someone’s decision on this matter would not be made in a vacuum. They’d be affected by their experience of healthcare inequality, poverty, loneliness, relational conflict, past trauma, addiction, homelessness, undiagnosed mental illness, and a host of other potential factors.

‘Slippery slope’ argument should not be dismissed

With this legislation, we face the prospect of Scots opting for a state-assisted death because they lack the support necessary to live. I don’t see how any amount of legal drafting could prevent this.

Those tasked with making possibly life-ending decisions would not have perfect insight into an individual’s circumstances or inner feelings. In my view, opening the door to such injustices should be unthinkable.

UK campaigners supporting a change in the law have not provided satisfactory answers to concerns about vulnerable people

Critics also point to the potential for legislation to expand in its scope over time. This concern, sometimes called the “slippery slope” argument, should not be dismissed out of hand. Countries with long-standing assisted suicide laws have become much broader. Canada, which allowed “assisted dying” for terminally ill people in 2016, is now home to the most permissive euthanasia regime in the world.

UK campaigners supporting a change in the law have not provided satisfactory answers to concerns about vulnerable people. And they cannot rule out future expansion of an “assisted dying” law on the basis that limiting access to people with terminal illnesses is discriminatory.

The only sure-fire way to rule out severe injustices and permissive legislation is not to change our law in the first place.

- If you are dealing with suicidal thouhts, it’s important to tell someone. You can call Samaritans at any time on 116 123, or email jo@samaritans.org

Jamie Gillies is a commentator based in the north-east of Scotland

Conversation