People are the experts in their own communities – none more so than those who have lived there for a long time. They can contribute valuable experiences and information which can help shape decisions that will impact their lives.

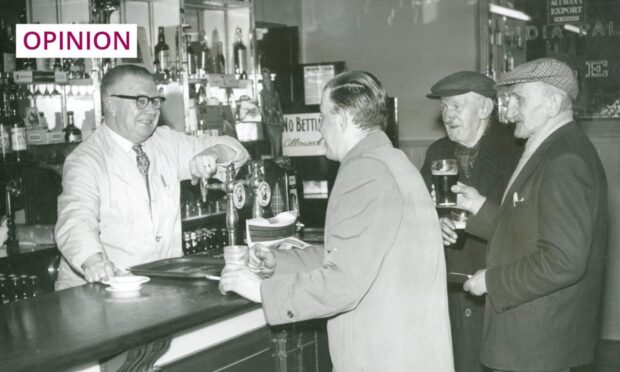

I’m one of the co-founders of a north-east organisation called Open Road, and we recently undertook a series of coffee mornings called Harbour Memories. We had a brilliant time meeting with a whole host of people who shared incredible recollections of the harbour area of Aberdeen.

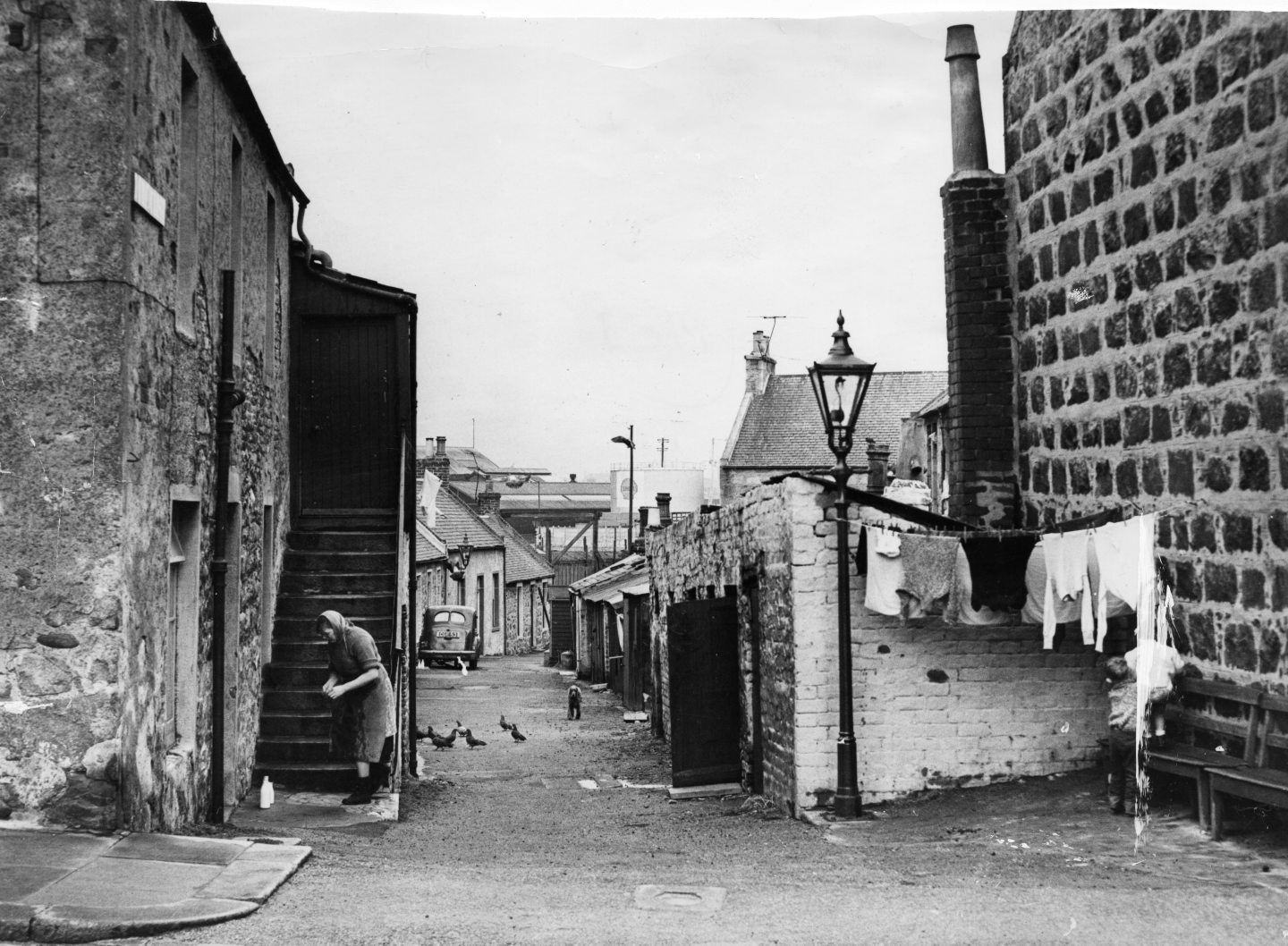

One of them was Chris Gove, who grew up in Old Torry and is an active member of the Torry History and Heritage Society. Chris is a natural storyteller and has many tales to share about the community he grew up in and knows so well.

Chris makes no pretence that the past was idyllic. However, his memories of Old Torry are not all stories of poverty, but also of community spirit and a sense of belonging. One of my favourite tales he told us is an example of how failure to consult a community can backfire, even if the decision made is full of good intentions.

Old Torry used to be home to Aberdeen’s deep-sea fishing community, and many of the men who lived there worked on the trawler boats, including some of Chris’s family.

Men in the same family often worked on the same boat. So, if a boat went down, the whole male side of a family could be wiped out, leaving their surviving relatives facing poverty. These were the days before the welfare state was established and, in times of need, the community would gather round to support the family when men were lost at sea. This is one of the reasons why fishing communities are so close-knit.

To make matters worse, at that time you weren’t employed by a boat, but instead signed a separate contract for each fishing trip it undertook. Contracts were often repeated and were civic agreements. This meant that if you failed to turn up, you were in breach of contract and had also broken the law and could, therefore, go to jail.

This situation would cause a family considerable financial hardship. Not only would there be no wage from the missed trip, but he also couldn’t work for the weeks he was in jail for breach of contract.

Underestimating superstitions

Fishing communities have a strong relationship with the church, which would often assist a family in times of need. In an effort to provide support for people in Torry, the church decided to build a nunnery there.

The nuns it housed were tasked with assisting families who faced destitution if their menfolk drowned or couldn’t work. However, if anyone from the church had consulted the residents of Old Torry, they would have found out that nuns would only make things worse.

Fishing communities might be religious, but they are also superstitious. One of the deepest held superstitions in Old Torry was that if you met a nun on the way to a boat to undertake a fishing trip you were contracted to work, you were guaranteed to drown.

This superstition was believed in so deeply that men would prefer to break their contract and return home, knowing they would be arrested and sent to jail, rather than go on the trip. Two weeks in jail was preferable to the risk of being drowned, even though it left their family with no income.

Record local history as it happened – so we can remember and learn

Chris’s father was one of many men who met a nun from the church’s nunnery in Old Torry on his way to a boat. He simply turned around, went home, packed a bag and waited for the police to come knocking at the door.

You can imagine the reception the nuns received from the womenfolk when they banged on the door saying they were there to help.

After a year or so, realising the nuns were making the problem they had been tasked to help alleviate worse, the church closed the nunnery down. You can still see the red granite building halfway up Victoria Road, which has now been converted into flats.

Though intentions were good, if only the church had asked the community’s opinion on ways it could help in the first place.

Story-sharing sessions are an essential way to save and record local history as it happened from those who were there. They are beneficial to help tackle social isolation and have a positive impact on our mental health and well-being.

They are also an opportunity for local authorities to find out more about the communities they serve and the lived experiences of residents, what they know and what matters to them. This knowledge and expertise can contribute to solutions for making the places we live better, as well as recording a good story that may otherwise be lost.

Lesley Anne Rose is a writer, creative producer and co-founder of Open Road, an Aberdeen-based cultural organisation

Conversation