The police officer looked straight at me and shouted: “What are you doing, what the **** are you doing?”

I tried to explain I was out for a walk and his response suggested he was about to spontaneously combust, before his attention was diverted by a bottle crashing into the ground and flames suddenly erupting a few yards away from him.

As I turned to move away, a couple of locals approached me and asked why I was in their neighbourhood – in Brixton, in London, in the midst of riots in September 1985.

Suddenly, I realised I could be in trouble and I mumbled something about trying to get to the Tube station. And one of the duo piped up: “Are you Scottish?”

I replied yes, indeed I was, and the tension dropped a few notches. His pal abruptly told me: “Okay, you better get out of here, mate, we don’t have a problem with you.”

Current unrest in England reminds me of Brixton riots

It’s a conversation I’ve never forgotten and, as rioting and looting engulf communities in England from Southport to Hull and Liverpool to Bristol, I’ve been reminded of my own experiences of the febrile atmosphere which surrounded life in the British capital back in 1984 and 85.

I’d travelled down in search of work as unemployment spiralled in Scotland, following the closure of coal mines, car factories and other manufacturing plants.

A job in a freezer department at BHS hadn’t exactly been on my radar a few years earlier at university, but there wasn’t much demand for classicists and archaeologists in Maggie Thatcher’s brave new world – unless perhaps you were Indiana Jones.

One or two things struck me about that London supermarket. In the stock room, on the labouring shifts and within the trash depot, most of us were Scottish, Irish, Asian, African or Caribbean.

Life was growing more difficult…then came the riots

Our bosses were talking about mortgages and buying new cars. The rest of us had to focus on finding rented properties and affording Tube tickets. And, even then, it was growing more difficult.

In terms of racism, those who were not white were forced to suffer regular doses of abuse from customers and most bit their lips. The shoplifters who were caught on a regular basis often resorted to swearing with a bit of prejudice flung into the mix.

But it wasn’t them who made my hackles rise. It was the well-to-do, smartly-dressed poshos who indulged in remarks about coconuts and watermelons and mocked my colleagues’ accents who caused the most offence.

The type of idiot who dropped bananas on the floor and waited for black staff to pick them up. Horrible behaviour – which became a feature of football matches in the following decade.

Fraught stand-offs and elongated skirmishes

For my part, I was “Jock” this, “Jock” that, “Duncan Disorderly”, “Hamish” and “Kiltie boy”, which was water off a duck’s back. But I didn’t have to contend with the naked racism which I witnessed on the trains home, much of it directed at Underground staff.

None of this is an excuse for the violence of the Brixton riot in 1985. It was sparked by the shooting of Dorothy “Cherry” Groce by the Metropolitan Police, while they sought her 21-year-old son, Michael, in relation to a robbery and suspected firearms offence; they wrongly believed that he was hiding in his mother’s home.

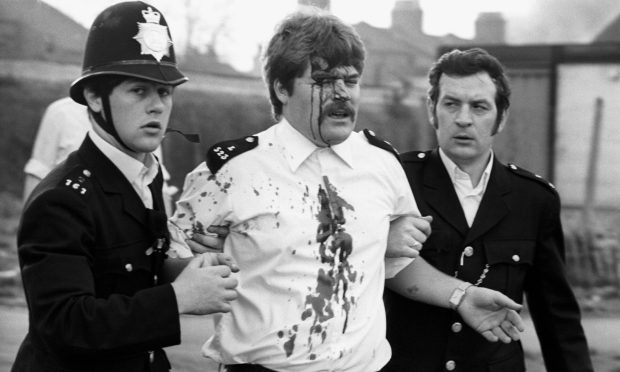

After two days of racial tension and increasingly anarchic riots, photo-journalist David Hodge had died, 43 civilians and 10 police officers were hurt, more than 200 arrests had been made, while 55 cars were burnt out, and at least 58 burglaries were committed, including acts of looting on individual homes and retail properties.

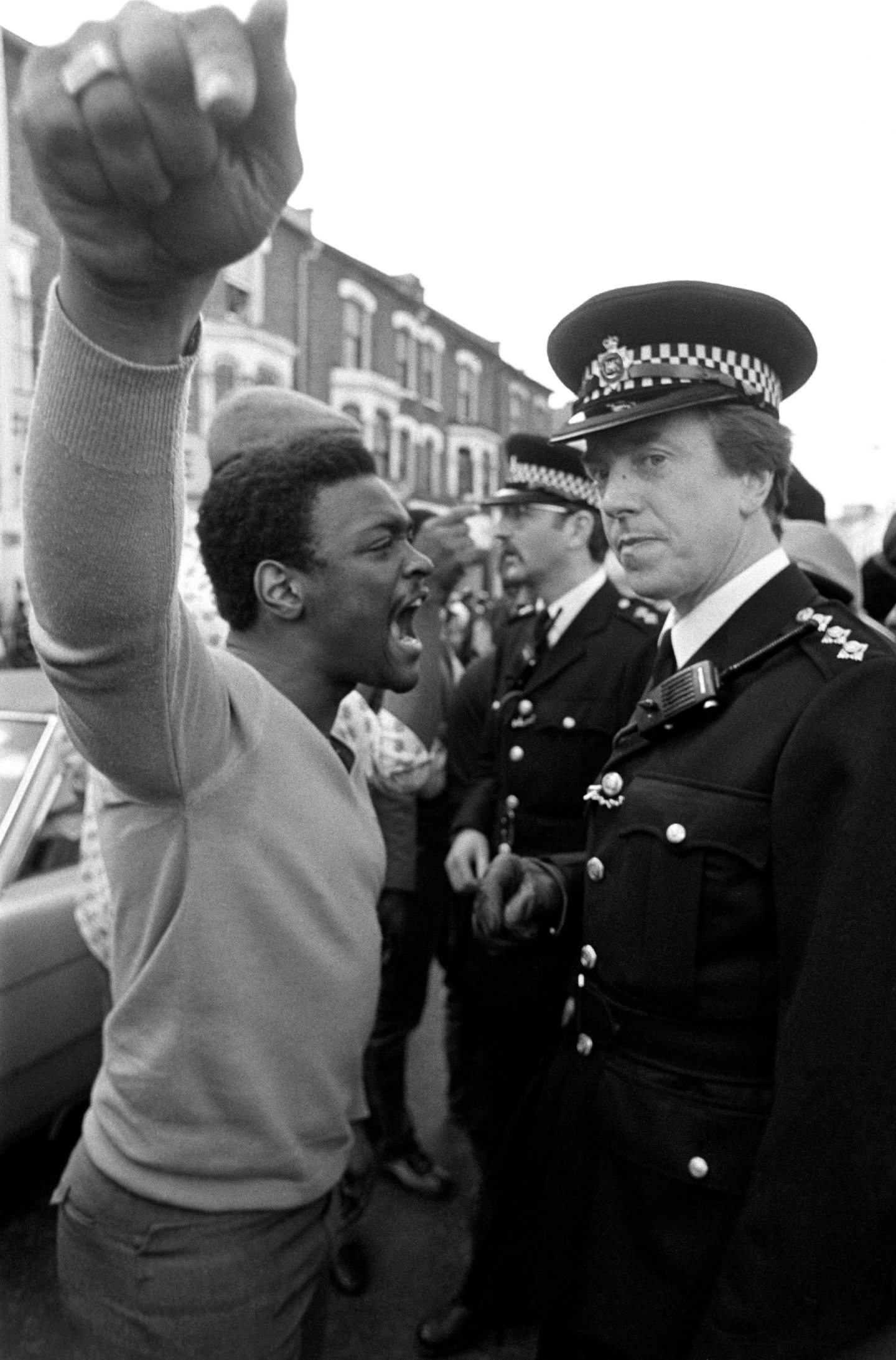

Hostility between the largely black crowd and the mostly white police force quickly escalated into a series of street battles and these developed into fraught stand-offs and elongated skirmishes in the areas of Brixton Road and Acre Lane.

What WAS I doing there? Experiencing the Brixton riots on the ground

I’d been working a check-out shift – on that Saturday, September 28 – and heard that trouble had broken out in the north of the city. The London Standard had only patchy details, but there again, it was a volatile and fast-developing story.

In these days, there were no 24-hour news channels, let alone social media. No Twitter trends or Facebook posts or anything which has inflamed the current civil unrest in parts of England.

So, for whatever reason, I decided I wanted to find out for myself what was happening. I lived not far from Brixton – it was within walking distance.

And so I walked. There was nothing much at first on the journey, then gradually, the screech of police cars and fire engines. A series of small explosions, which turned out to be petrol bombs; screams from different groups of people; cries of “Help” from one or two women who were caught up in the melee; and a rising tide of fury.

At one point, I turned the corner and the devastation was like something from a dystopian film. Not Mad Max, since that hadn’t yet been released, but the same sense of society being ripped to pieces by desperadoes.

Shops had burnt-out facades, glass was everywhere, ambulance staff were dealing with casualties on the ground and police were grappling with a situation they were struggling to control.

I knew that I shouldn’t have been at that ghastly scene, and the police officer who confronted me was correct. What WAS I doing there? In my early 20s, I’d wanted to check out for myself whether the newspaper stories were exaggerated. They weren’t.

‘I fear the violence isn’t going away’: Parallels between Brixton riots and today’s scenes

And yet, looking back, I can see parallels between then and now. Many of the far-right thugs who have terrorised communities in recent days have done so without any appreciation of why they’re behaving in that fashion.

How do you help or protect your own town by stealing from shops and setting fire to hotels? You don’t – it’s madness.

Back in 1985, the punishments for those arrested were predictably harsh.

There were subsequent riots in Peckham and Tottenham in London and in Toxteth in Liverpool.

And many of those who have been captured on CCTV plundering laptops and cameras – and, more bizarrely, steak bakes and bath candles – will probably end up in court and have plenty of time to reflect upon the stupidity of their actions.

Yet, I fear the violence isn’t going away.

Back in the 80s, groups such as the Anti Nazi League and Rock Against Racism were pushing back against those with prejudice in their hearts. Minorities got their act together. Hope not Hate was the message. Football clubs removed terraces and installed family stands. Positive steps forward.

But there’s not much of that confidence and collaborative effort in evidence at the moment. And I very much doubt the police or rioters would treat me the same way as happened during that Saturday night frenzy. I was one of the lucky ones.

Conversation