Perhaps I was slightly delirious after anaesthetic made my abdomen so numb even Mike Tyson at his peak would have given up thumping it.

I was miffed about missing my hospital lunch.

I’d gone to so much trouble ticking off the form for Friday fish and chips on the ward.

Ravenous after eating practically nothing due to my big cancer operation the day before.

The surgeon who saved my life swept in and announced cheerily that I was good to go.

Home, she said; before lunch could be served, dammit.

I was looking forward to it because it seemed the height of luxury to be served fish and chips in bed.

Yes, those drugs I was on must have been mighty strong.

Perhaps it was a close shave looking back, as concerns over poor-quality hospital food boil over again.

Meals are so important to patients.

For NHS patients food could be the ultimate source of comfort

I suppose it’s the ultimate comfort food in the purest sense.

It has the power to lift or deflate the spirits – a powerful influence on our mental wellbeing and therefore our medical recovery.

Yet it doesn’t appear to be the highest of budget priorities as the NHS seems on the verge of cardiac arrest half the time.

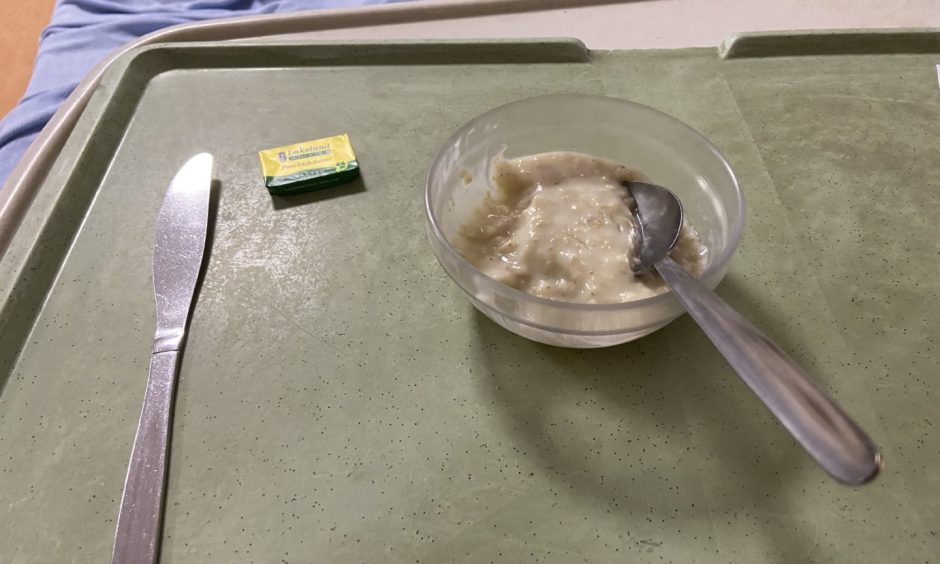

We heard about a shocked Nairn grandmother served a cheese sandwich for dinner after hours of fasting and surgery – followed by “slimy” porridge for breakfast.

We then discovered that 30% more was spent on food for criminals in Inverness prison than Highland NHS patients.

Around a miserly £3 per head for a meal in hospital.

That wouldn’t be enough for two packets of prawn-flavoured Quavers at Asda.

The first minister is now said to be personally driving efforts to improve Scottish NHS targets, but I doubt food makes the top 10.

It’s understandable that hospital bosses are quick to defend their culinary offerings as “nutritious”.

However, “nutritious” covers a multitude of sins; like lumpy sauce smothering a plate.

I suppose a cheese sandwich, soggy toast or a bowl of peanuts are all “nutritious” in their own way, but are they appetising and satisfying?

Something patients might look forward to while killing time in bed?

So meeting nutritional guidelines is currently a basic-level achievement which doesn’t cost much or get any better.

I suspect plenty of uneaten food goes straight into the bin, which means not a lot of nutrition makes it through.

This assumption is based on my own personal experience of hospitals in Aberdeen and Birmingham, where I went to see different relatives in recent times; one period covered multiple visits over 12 weeks.

In fact, I formed a distinct impression that more food was going out in black plastic disposal bags than had come into the wards.

How on earth was this?

I guessed it was partially caused by heavy (and costly) over-ordering on wards – a problem highlighted by Aberdeen hospital managers last year.

Meanwhile, Highland hospital bosses responded to recent criticism by pointing to the magnitude of their task in producing 40,000 meals a month.

Cruise ships do something similar on a much different scale.

NHS food of nutritional level has not been a priority for years

The colossal Oasis of the Seas serves nearly 30,000 gourmet meals every day, in an impeccable manner no doubt.

But for them, “food glorious food” is their number one priority for customers occupying cruise beds – and that’s where the big money goes.

NHS food of a higher quality than basic nutritional level has not been a priority for years by the look of it.

Billions of taxpayers’ cash pours in, but not enough seems to reach the kitchens; the pecking order puts them behind waiting lists, A and E, funding staff, new equipment and fixing crumbling buildings.

When my wife underwent two major orthopaedic operations over the past four years, I took in supermarket food because she couldn’t stomach the grub – triggered by a stale cheese sandwich for her first post-op “dinner” at Woodend Hospital in Aberdeen.

She only managed to take two nibbles; I know someone at another hospital who just ate cheesy Wotsits from outside.

I must say that my wife’s nursing and surgical care at Woodend was second to none, but catering was less so.

Are we prepared to pay for our own hospital food if it meant we were treated quicker?

Probably, but could we trust the monolithic, financially complex NHS to manage this properly?

A lot has been made about “better-off” prisoners, but that’s debatable.

However, various penal studies confirm that food keeps the peace in jail.

Prisoners have rioted over poor food, NHS patients won’t; they are too sick or nice to do that.

Which brings me to the subject of jam.

Maybe more jam would delight patients, but I’m talking about Jam the band.

Paul Weller sang, “What you give is what you get”.

It’s the same with funding hospital food.

David Knight is the long-serving former deputy editor of The Press and Journal

Conversation