It’s a phone call which I have never forgotten. An anguished message from my mother telling me that my sister’s fiance had been murdered in London.

Until that tragedy, which occurred at a stag party in 1993, Jean and Cormac had been preparing to celebrate their marriage in Scotland just a week later.

But, in an instant, his life was cut short by a series of fatal stab wounds as he attempted to stop an argument between his family and two youngsters.

They were released in their 30s

It emerged later at the trial that the victim – a kind and decent Irish lad without a bad bone in his body – had been subjected to horrific injuries.

The perpetrators were found guilty and sentenced to “life imprisonment”. Yet, less than 15 years later, they were both released while they were still in their 30s.

That question has troubled me ever since. Should people who kill another human being be allowed to rebuild their own lives when they have denied that chance to others?

I should make it clear that I’m neither a member of the hang-em-and-flog-em brigade, nor a believer in the death penalty. Prison rehabilitation can and does often work.

Yet, when I look back at the all-enveloping grief which followed Cormac’s death more than three decades ago, it’s difficult to absolve those who committed such a heinous act.

All the promise was snuffed out

A year after the wedding which never was, Jean wrote a piece for a Sunday newspaper with the headline ‘Life after Murder’ and reflected on how her existence had ground to a halt “with so many plans we had made together destroyed forever”.

“Those responsible for this will regain their liberty one day and be able to go home to their loved ones. That is why it is so hard to even think about forgiveness at this stage.”

Every case is different. Some people might imagine that it’s easier to sympathise with the person who flings one punch in a pub brawl and ends up in jail than those who carry knives and are prepared to stick them into somebody else 20 or 30 times.

But, ultimately, the end result leaves the victims’ families and friends with the same result; the loss of someone they loved to violence, whether premeditated or not.

Families’ feelings should be foremost

Last week, it emerged that Daniel Stroud, the former Cults Academy pupil who stabbed classmate Bailey Gwynne to death in 2015, has reportedly been released from prison.

The 25-year-old was cleared of murder following a six-day trial at the High Court in Aberdeen where he was found guilty of culpable homicide and carrying weapons.

His sentence was nine years and now, in his mid 20s, he is reportedly free. Is that justice?

And yet, for all the media attention and occasional public anger at what are perceived as lenient punishments for criminals, the statistics show that sentences are actually rising.

That’s a state of affairs which has been highlighted by Neil Lancaster, the former Metropolitan Police officer who has become a best-selling author in the Black Isle.

We are locking people up for longer

He told me: “According to recent data, sentences for murder have been significantly increasing over the past few decades, with the average minimum term rising by over 60% – from around 13 years in 2000 to 21 years in 2021.

“Crime is shocking, and rising fast, and it feels like things are deteriorating with the almost casual attitude to violence. Zombie knives are carried at will, increasing the murder rate owing to the devastating injuries they inflict.

“Policing is, like many public services, struggling to cope, so it’s an easy fix for politicians to shout loudly to increase sentences to appear proactive and tough.

There’s less chance of rehabilitation

“We now regularly see 30-year sentences for crimes that would have historically attracted a 16-year minimum term. The question remains, does it work?

“My view is that it can, but with prisons bursting at the seams, staffing crises and a depleted probation service, it rarely does.

“If we could invest in serious rehabilitative work in prisons, we could maybe have a real impact, but the costs are huge, and it will take many years for the effects to be realised.

“Politicians are not patient. They want to get elected, and that’s a treadmill, and is simply a short-term view that will solve nothing.

It’s a bleak outlook

“Basically, we are locking people up for longer than ever, but violent crime continues to soar, which means it’s not working. So why do we do it?

“To protect the public from violent criminals? Sure. To punish? I guess. To rehabilitate? I hope so. But society needs to decide what it really wants or we won’t get anywhere.

“The prisons will get fuller and crime will continue to soar.”

As the man who helped transform Peterhead Prison Museum into a five-star visitor attraction, Alex Geddes has long pondered the treatment of offenders.

Yet, even as he discussed one grievous miscarriage of justice from history, he admitted that nothing was cut and dried about crime and punishment, past or present.

Wrongly convicted and spent 19 years behind bars

Mr Geddes said: “During my research over the years, this is a subject that has caused me considerable consternation. Every situation should be judged on its own merits.

“Some cases may have extenuating circumstances while others simply have no excuse.

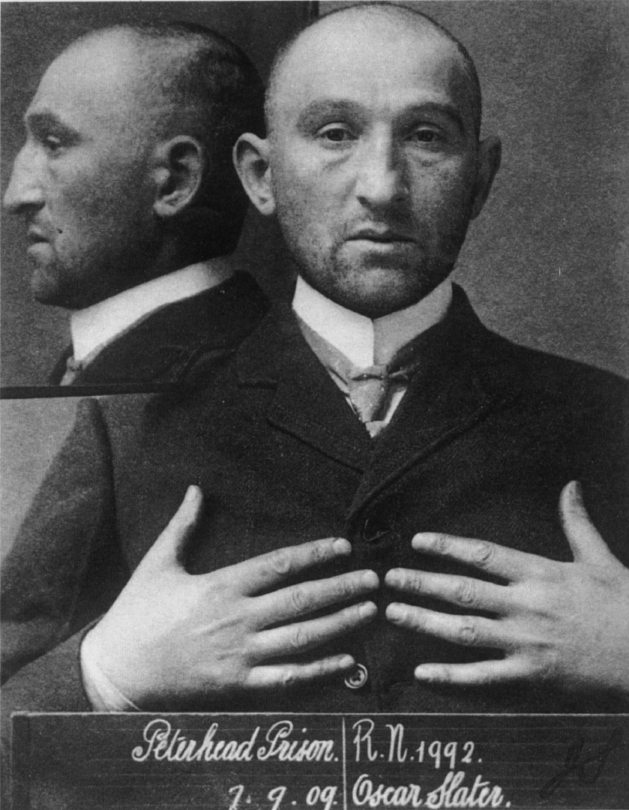

“Looking back in time – and I know forensic science and police detection have moved on significantly – what about Oscar Slater who was sentenced to death for murder [in 1909] which was later commuted to life imprisonment?

“It was identified 19 years later that he was indeed totally innocent. If they had hanged him, it would have been far too late to say sorry, but equally he spent 19 years in hard labour [in Peterhead] for a crime he never committed.

It can be a dreadful dilemma

“And yet, many people are simply guilty and, putting myself in the shoes of a victim’s family or relative, could I honestly say they should be released early?”

That’s the question. My sister never recovered from her loss. Nor the phone call she received from Victim Support in 2007 telling her Cormac’s killers were being freed.