The things we take for granted? Oh, after my time in the Gaza Strip, it dawned on me, just how much we really do take for granted in our everyday lives.

I woke in my apartment in Bethlehem after having left Gaza the day before. At the flick of a switch I had electricity. I boiled the kettle, turned on my laptop, connected to the internet and listened to the Today programme on Radio 4. All impossible in the Gaza Strip.

After a steaming hot shower, and feeling properly clean for the first time in days, I stepped on to the streets of Bethlehem and walked in no particular direction.

For sure, the air is far from pure here, but it’s perfection compared to the lung-choking air in Gaza City. Everything’s relative isn’t it? I mean, before I’d been to Gaza, I was never impressed by the rubbish lying around Bethlehem. The environment is way down the list of priorities here. But after having been in Gaza, I found Bethlehem rather clean.

I soon ended up near Manager Square, but not in it. I avoid it like the plague. Sorry, but I find it tacky and touristy and lacking in any spirituality whatsoever.

Down a tiny alleyway, I went to see my coffee man. This guy is a gem. He owns a tiny shop, more like a kitchen really, from where he prepares freshly-made sweet mint or sage tea and coffee flavoured with cardamom pods. He works every hour God sends, running around with small trays of tea and coffee, serving not tourists but local shop owners. In Manger Square, if you’re stupid enough, you’ll pay up to an eye-watering 12 shekels for a coffee. I pay my man the same as the locals do, two shekels, which is around 40p.

Suitably refreshed, I headed to the food market and stocked up with veg from the abundant produce on display. I also visited a very good butcher I know. Lamb and cow carcases hung from hooks in the roof, and sawdust littered the floor, just like the old-fashioned butchers we used to have in the UK. I planned to make chilli, so pointed at a carcase of beef, explaining what I wanted and the butcher expertly cut a sizeable chunk with the fat on. He then proceeded to put it through his mincer. Wow, mince doesn’t get any fresher than that, I thought.

With my bag full of tomatoes, peppers, kidney beans and fresh bunches of herbs, I took it all back to my apartment and bunged it in the fridge. I was looking forward immensely to that evening, when I’d cook my first meal in over a week.

Since it was Friday, which meant potential scuffles after prayers, providing photo and interview opportunities, I really should have crossed through the West Bank Barrier and taken the bus to Jerusalem. But you know what? I couldn’t be bothered. Not today. I could go next week if I wanted, but after Gaza, I was tired and just wanted to stay put. That said, I learned from my friend Adel, that there were demonstrations planned for after prayers in Bethlehem. As ever he said to me: “Be careful.”

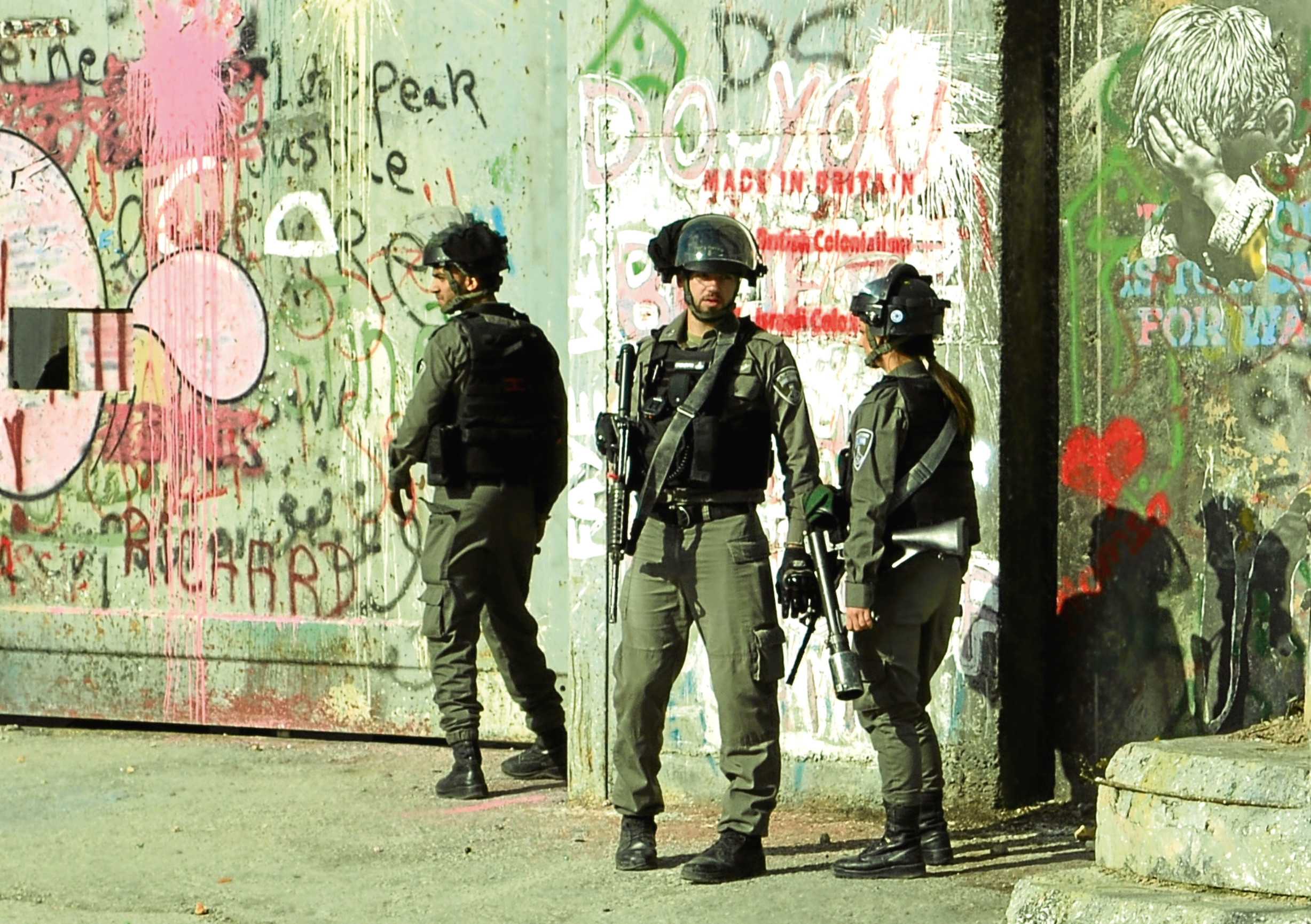

Stab and bullet vest on, I started to walk. Checkpoint 300 is only a couple of hundred metres away from my apartment and the closer I got, I could hear tear gas being fired. I turned the corner and came face to face with the sight you see in my photo, Israeli soldiers were actually standing on the Palestinian side. They’d come through a secure metal gate in the wall. I’d never seen that before. They didn’t venture far, for even though they are armed to the teeth, if they were ever caught by the crowd, I’m sure they would be lynched. They were currently being subjected to a barrage of stones and other such missiles.

I quickly showed my Israeli government press card that was hanging on a lanyard round my neck. A soldier nodded, and told me to stand back, as his comrade fired a new round of tear gas directly at the crowd, standing maybe 100m away down the road.

After taking some photos, I wanted to experience this from the other side, so I quickly ran back the way I’d just come, took a shortcut through tiny streets in a nearby refugee camp and moments later was standing near some protesters, looking back at the wall and the soldiers where I’d just been.

Most protesters had scattered, the tear gas too much for them, but a hardcore remained. As another volley was launched towards us, which makes a deep, scary, deafening sound, I crouched down behind a small barricade that had been placed up against a lamppost. As the volleys ceased, I stepped out and got my photo from behind the tyres that were burning all over the road. Suddenly a young man ran up from behind and stood right beside me. He prepared his slingshot. I didn’t ask him to pose for this photo, I took it just as he fired his sling towards the Israel soldiers.

It seemed utterly ridiculous, a slingshot fired towards a wall, and soldiers armed with guns and tear gas.

“Why are you doing this? These guys could shoot you dead,” I asked him.

“It’s for Palestine,” he replied, before retreating to his hiding place. I shook my head at the ridiculousness of it all.

I picked up a spent tear gas canister that had been fired previously. It was still warm and stank of sulphur. I’m having this one, I said to myself, and stuck it in my bag. A rather unusual souvenir, I thought.

For as dangerous as it all seems, and while not wanting not trivialise it, it’s a game really and happens like clockwork every Friday all over the West Bank at numerous checkpoints. Not all, but some mosques “encourage” this behaviour. I’ve also been told by many friends in Bethlehem that the Palestinian Authorities themselves actually pay these young guys to throw stones at soldiers. They pay them maybe 20 shekels, around £4. This is what I was told, but of course I have no idea if it is true or not.

Israel classes anyone who throws stones at their soldiers as terrorists. The minimum jail sentence if you are caught throwing stones is three years. If the prosecutor can prove that the stone thrower meant to cause actual bodily harm, he can go to jail for 20 years.

About 99% of the people in the West Bank want nothing to do with this kind of behaviour. They know it only antagonises Israel, and at the end of the day does nothing whatsoever to help their cause. But of course on TV news reports we see these scenes and then are led to believe that the people here are all terrorists.

Once the young men had made their point, whatever their point is, it all calmed down, and they disappeared. The IDF retreated behind the safety of their wall, the fires were extinguished and the streets cleared by Palestinian workers, as taxis once again went about their business.

I actually returned to this very spot a few hours later and it looked like nothing had happened.

“Just another normal Friday in the West Bank,” I said sarcastically to myself, as I walked back to my apartment.