What did illuminated manuscripts ever do for Dundee? This question arises on looking at a colourful medieval book which will be on show at the city’s new V&A, Scotland’s first design museum.

A flippant ignorance is what museums are there to correct. The 19th Century urge to gather objects and so educate the people was no doubt corrupt but also benign – the acquisition of knowledge was in the pursuit of progress, the belief that humans were inexorably improving.

Museums were encyclopaedias in three dimensional form, precursors of the internet and readily accessible knowledge. They preserved traces of human ingenuity. They were also the idea of the rich – collecting is a wealthy pursuit. Which is fitting as designed objects, things worth saving, are invariably the result of wealth – only the rich can commission an illuminated manuscript, for example.

We no longer think in terms of progress – it’s seen as naive, the idea that things can only get better. Instead we “develop” in the hope that we are doing more good than harm. People who run museums call this age the Anthropocene – the human era. We are the most important factor on the planet, and are engaged in a race to develop before we destroy everything. So much for progress.

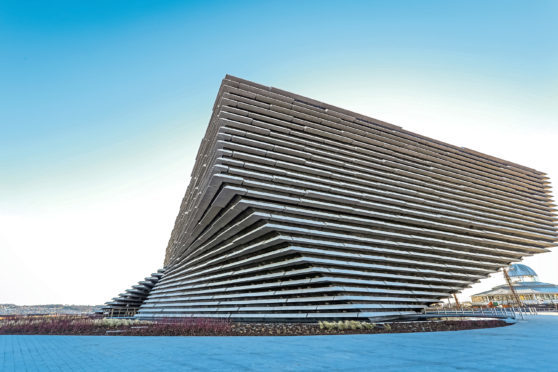

On a local scale, the balance is between development and democracy. V&A Dundee has cost around £80 million, most of which has come from the people of Scotland. Had you stood on Dundee’s Union Street 10 years ago and asked people what £80 million should be spent on, it’s unlikely they’d have said a squat museum that looks like a prop from Star Wars.

More likely they’d point to the exceptional poverty which exists in the city and ask for the wealth to be given to the people. Why build a museum when your people are starving?

Now that the building is there, people have come to love its bold shape and flinty lines. So much so there is anger that no sooner had the museum been built but a new office development is set to obscure the view from Union Street.

Site 6 on the masterplan for the waterfront will become commercial offices. Still under construction, it has none of the architectural ambition of the museum. It’s a box designed by the rules of low cost and easy maintenance.

It appears like the city has poked itself in the eye – build one amazing museum and then ruin the effect with a steel box. It’s like taking your illuminated manuscript and scribbling over half the page.

The idea is that the £80m for the museum will raise a further £1bn in new economic activity. Site 6 office block will be popular because of its location in the redeveloped waterfront, and the occupants will make money which will be spread within the city and hopefully make everyone a bit richer. The hope is design will help Dundee’s poor.

This model of using public money to leverage lots more private investment and spark economic activity has one big downside. It’s not democratic.

Elected politicians initiate the proposals and cough up public money, and there is always a process of “consultation”, but ultimately commerce wins. Once the council or the government have put their signature to such a deal, there is precious little you and I can do about it. These developments start in the democratic world then rapidly enter the private one, from the accountable to the secret. Site 6 is written into the commercial deal. It is part of the quid pro quo between the people and the developers.

City councillors are rightly proud of getting such a big project off the ground, but in so doing they shake hands with the development devil. To make building the V&A worthwhile, a little bit of the city’s soul must be sold.

This is how it is done everywhere – to build Glasgow’s Commonwealth Games facilities, locals were turfed out of their homes. Demolishing Edinburgh’s St James Centre left locals as bystanders as their community was arbitrarily rearranged. The model by which we develop suits the long-term planning of investors, but can insult the communities being developed.

This democratic deficit needs to be corrected. It is though, secondary to the larger issue of holding the investment to account. There can be no democratic shortfall when it comes to who benefits from the economic boost of the V&A and surrounding developments.

There is a large body of socio-economic study which shows that the optimum design for society is not to have extreme wealth and poverty side by side. The eras that produced the beautiful objects in the museum were also times of suffering and inequality.

If Dundee, and Scotland, are to be truly proud of the wonderful V&A they must never lose site of its democratic purpose. To illuminate not just our minds, but the truth of our society. The greatest design humankind can aspire to is a just place, rich in culture and community. May the V&A deliver for all.