As I write this, winter sunshine is streaming into the attic room where I have temporarily shut myself off from the world to think.

It is cold still, a brittle cold, but the light is beautiful, and it lifts my spirit the way it reflects off the white wood floor. I do not usually work here but I am comfortable sitting on a grey and white tartan rocking chair, laptop on my knee rather than on my desk, and it seems almost like sorcery that the thoughts in my head are becoming electronic symbols on a page.

There is an intimacy about this process: thoughts straight from my head as I write, into yours as you read, via words on a page.

How powerful words are! With them, I tell you my location, mood, thoughts and feelings. I remember interviewing the late Iain Banks and being struck by his notion of the writer as a wielder of power. Banks got a kick, he told me, out of making people angry, scared or turned on, just by “squiggles on a page”. The writer was a mood controller, orchestrating like a conductor of music, or the choreographer of a ballet.

It’s true that, for good or bad, our words can affect the emotions of those who hear them. That is their power and their potency.

But perhaps the most important function is their ability to create connections even between strangers, lessening the sense of isolation that we can all feel, whether we are tucked away in an attic room or at the centre of a crowd.

After my last column, which was about the bitter-sweet nature of Christmas and the sense of loss that sometimes accompanies it, I received some mail. One correspondent wrote to say she had been having a bad day, struggling with the loss of her husband, until she read the words and remembered the power of hope.

Her email was my first Christmas present of the year, a gift delicate as the glass baubles on my tree. Why? Because in saying thank you, she gave me something back. My words and her words forged a connection between two strangers. They gave me a glimpse into her life, her sadness and her strength.

As a writer, words delight but also frustrate me. They rarely capture exactly what I want. We can all get jaded, but her correspondence was a powerful reminder of why I keep trying. When I first wrote novels, the motivation was a kind of emotional empathy. I wanted to make connections with people by capturing something of what it is to be alive; to tell the truth of the world as I saw it, in all its glory and its sorrow and its complexity.

As a little girl, I was a silent child, notorious for hiding behind my mother’s skirts. Nobody could coax me to speak. It’s probably no coincidence that I ended up in a job that gave me a voice, and more importantly gave a voice to those I talked to.

Undoubtedly, I have sometimes written harsh words as a journalist – but always for a purpose. One of the most touching messages I ever received was from an interviewee who contacted me the morning our conversation went to print. “For the first time in my life,” she texted, “I feel like I have been listened to.” It’s an important function of journalism.

Sometimes, it’s hard to listen. It involves patience for other people’s “stuff”. But we all have “stuff” and we all need to listen, to be person-centred in a world that seems increasingly split off from the emotions of others. Perhaps that is why it is so dispiriting to look at the words used on social media: the ugliness, the cowardice, the ruthless cruelty they contain. Things people would never say had they to face the person they insult – or even had they to write using their real name.

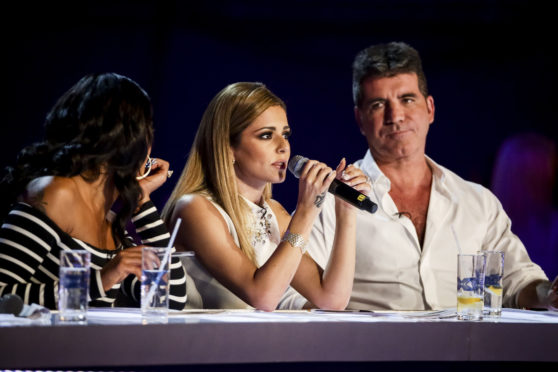

I am no fan of the singer “Cheryl” but reading the vicious comments about her recent come-back television performance took my breath away. It wasn’t opinion; it was assassination. Some people seem to feel that making someone else smaller transfers extra inches to them.

It has been nice spending this short time with you in my white, attic room as the year draws to a close. My words have invited you into my world and that is the point – words are bridges or they are bombs; they unite or divide. Be careful, we think, when we get into a powerful car, or use dangerous machinery, or face an icy hill in winter. Well, I have had the same painful, physical injuries in life that everyone has, but there is no doubt that the deepest cuts, the most lasting damage, have come from words. Our social discourse reflects the values that we hold as a society and in 2019, I hope we use words with increased respect, increased tolerance – and increased kindness.

Catherine Deveney is an award-winning investigative journalist, novelist and television presenter