The Albanian communist regime was one of the cruellest in Europe. It executed around 25,000 of its own people and sent tens of thousands to labour camps.

Run for almost 50 years by paranoid dictator Enver Hoxha, communist Albania was almost unique.

It didn’t cosy up to its big communist brothers and in fact Hoxha’s Albania fell out with not just neighbouring Yugoslavia but also the USSR.

Naturally it had nothing to do with the capitalist west so, for decades, Albania was stuck in splendid self-imposed isolation. Hoxha even had 173,000 concrete bunkers built and scattered all across his country.

Lookout posts for the dreaded invader, whoever they were supposed to be.

With no freedom of speech, or worship, nor right to leave, and dreaded political prison camps, Albania was a real-life European Stalinist system.

And the only way to keep such a repressive system in place was by force and fear. This was done, expertly, by Hoxha’s secret police, the Sigurimi.

Other European countries opened their doors many years ago to the evils of their communist past, but Albania has dragged its feet.

It wasn’t until 2017 that Albania opened a museum dedicated to its dark past. The “House of Leaves” is the HQ for Hoxha’s former secret police.

I’ve heard differing explanations for the name, ranging from it’s called this due to “things hidden in woods”, could that be bodies? I prefer the explanation that it’s to do with the “leaves” of books and files on people.

I went to the building, but was informed I could take no photos of the exhibition.

What? That didn’t make sense. I said it was my work, explained my passion for the subject, mentioned I’d done the Stasi, various former KGB buildings, and recently, Saddam’s torture prison in Iraq.

“Surely the objective of such a place is to educate and, more importantly, to spread the word and inform?” I said to the director. “I’ll write a double page on this, with photos and…”

“Sorry, no photos. You can go in and look, but no photos.”

“My article on this place won’t even get printed without photos. It won’t be accepted for publication. Nobody wants to read two solid pages of text. It needs photos,” I explained.

“Maybe you can get official written permission from the Ministry of Culture for photos.”

Oh dear. I’ve come across this red tape many times before, and if it was anything like it is in Russia, I’d be getting my pension before getting anywhere regarding this.

I walked off, shaking my head, back to my hotel and sent an email to the ministry.

Forty eight hours later, no reply, so I went back to the museum, tried again and asked for help.

Why was I being stopped from promoting this place? It made no sense, yet no one seemed too bothered.

I persisted, and finally, the director helped by emailing the same person at the ministry I’d had no reply from.

The next day, I finally received an email confirming that I would be allowed to take photos.

Later that day, I would spend around two hours in the House of Leaves and the photos you see here I took with written permission from the Ministry of Culture.

The building is set in its own private garden; imagine a huge detached house on three or four floors, with rooms that run off each corridor.

Each room contains a small exhibit, with information on Albania’s long, complicated history, the rise of communism and then what happened for decades, under its name.

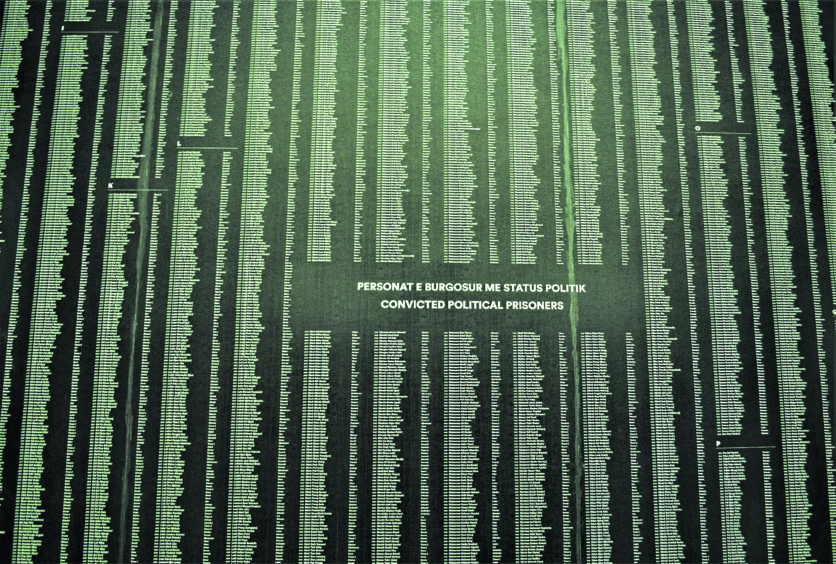

The detail is thorough, and all explanations are in Albanian and English, with lots of photos and even video clips of interviews with former prisoners of Albania’s prison camps.

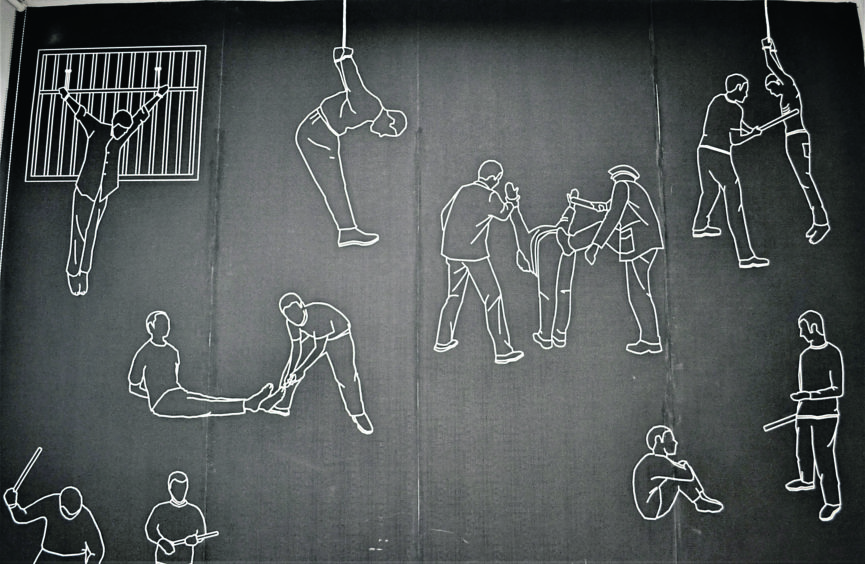

In sometimes graphic detail, the museum makes it clear how Albanian society was totally controlled.

In some communist countries, it was more relaxed, for example Hungary was often referred to as having “goulash communism”, but no such luxuries in Albania.

Hoxha’s Stalinist regime in Albania was total. A complete monopoly on power. It controlled all aspects of its citizens’ lives, economy, education, art, science, media, morals, private life, ideas, feelings.

In the dark room, where photos of citizens being spied on were quietly developed, I have to admit to feeling somewhat unnerved.

In other rooms it was explained how the Sigurimi tapped telephones and intercepted the mail.

Typed documents, original I think, with names blanked out by black pen to spare identities, showed who was being spied on and what was reported back.

There was no right to privacy in Albania, the use of hidden microphones to eavesdrop on private conversations was widespread.

And once an individual was labelled an “enemy of the state”, it wasn’t just him or her, but their entire family that was blacklisted.

This is still the practice in today’s North Korea.

Listening to the interviews with men who had been locked up and near worked to death in labour camps was harrowing.

And what we must remember, in fact, no, not simply remember, but shout from the rooftops, is that this wasn’t under Nazi Germany in the Second World War. This was happening in Europe; political prisoners being locked up in labour camps in the 1980s.

Shocking that this happened all over eastern Europe and eternal shame on those who did it.

But unlike Nazi crimes, no one is being prosecuted for it. Why? Because many involved in human suppression during the communist times are still in positions of power in today’s Europe.

On video, one man went to explain about his time in a labour camp in the 1980s. He said that if you had, for example, a broken rib, this is where they would keep beating you, on that broken rib, over and over.

No wonder people confessed to a number of things they never did.

Tragically, even in our very recent past, the US has used such methods as waterboarding in order to get confessions. Torture in my book.

It is pointless and degrading to humanity. Pointless because the person in pain will admit to anything just to stop said pain. I would.

Degrading? Surely, I don’t even have to explain why all forms of torture, both physical and mental, are degrading and should have no place in our world. Ever.

Like how today’s children in Germany are taught about Nazi crimes, children in former communist countries should be taken to and shown these places. The only way to learn about the past is to be aware of it.

On that point, how many other people did I see in the House of Leaves? No one. Not one other visitor.

I took a look at the visitors’ comments book, a dozen or so over the past days, a few foreigners also, but that’s it. Why is this place not bursting at the seams?

It’s almost like they don’t want to promote it. There is a general sense of discomfort associated with this building.

I have no complaints with the content of the museum at all. The information is superb, detailed and well thought out.

It’s just that strange feeling of, “We really don’t want to make a big thing of this place”. I can’t explain it any more than that. I promised I’d send this article to the ministry and have done so.

I say to the authorities, well done for opening this museum. You now need to promote with the vigour that say, the Stasi prisons in Berlin are promoted.

You need to let people take photos. I don’t use so-called social media but, goodness me, even I know the power of it.

Let people take photos, spread the word and get people talking about this place. Get groups of school kids in here every single day, no exceptions.

As for the press, we should be encouraged when it comes to writing about this place, not hindered by rules regarding photos and needing official permission.

To contact George directly about any of his columns, email nadmgrm@gmail.com