“What’s she been in?”

It’s a regular question in the Razaq house if we’re watching a film.

“That actress … you know, she was in that other thing we saw, the one about such and such.”

I’m always doing the asking and – much to Mr R’s annoyance – can’t concentrate on the rest of the movie unless I look it up.

Yes, I’m one of those people.

This week I found myself in a similar boat, only while Maya was enjoying her favourite cartoon, Bing, which for those of you who don’t know – and I’ll forgive you – follows the life of a toddler bunny and his friends.

In fact for months now I’ve been desperate to get to the bottom of a burning question.

Why does Pando (you guessed it, he’s a panda) always take his shorts off at the first opportunity and run around in his pants?

I cringe as I type the question into Google.

My momentary embarrassment quickly ebbs, however, as the search results come up.

And I’m shocked and amused in equal measure to discover that this weighty conundrum has been bewildering parents across Britain and America.

There’s even an official explanation – Pando, like many little ones, prefers the freedom of not wearing many clothes, especially when being active.

Underwear-flashing aside, it’s a fun series and each episode ends with a moral, so I don’t mind my daughter watching it in small doses.

I knew I’d have to be discerning when it came to television programmes.

What I didn’t anticipate was that such diligence would also be required in relation to books.

Mr R recently bought Maya several beautifully illustrated versions of the traditional fairytales.

But when we sat down to read them, we were both surprised and disappointed at how much the stories have been sanitised.

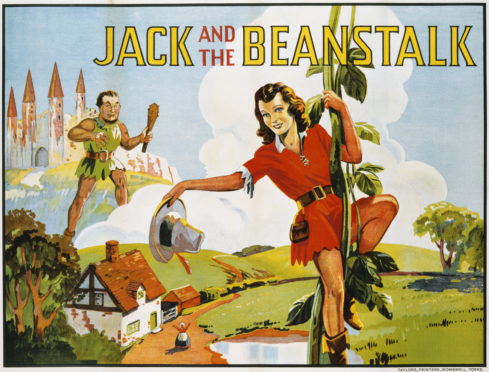

“Fee, fi, fo, fum! Watch out everyone, here I come,” the giant roars in Jack and the Beanstalk.

There’s no “blood of an Englishman” or grinding of any bones to make his bread.

And in Little Red Riding Hood, the wolf doesn’t eat anyone.

Instead, grandmother hides under the bed where her granddaughter joins her when the wolf’s attempt at gobbling her up is foiled by his nightcap disguise flopping over his head and covering his eyes.

It’s a far cry from the Charles Perrault interpretation, believed to be the earliest take of the folktale in print, in which Little Red Riding Hood climbs into bed and is devoured by the wolf.

Not a happy ending, but the lesson is spelt out – don’t listen to strangers – and is stronger for the peril.

I’ve noticed a parallel sterilisation with some of the nursery rhymes.

Certain lyrics have been changed for political correctness’ sake and that seems fair enough.

It’s the people on the bus who chatter, not just the mummies and the little piggy has roast potatoes rather than beef as not all of the children at playgroup eat meat.

But I’m less convinced about the farmer’s wife cutting up “cheese with a carving knife” instead of the mice’s tails.

I suppose the words I sang as a child are violent, but I’m pretty sure I turned out okay.

Moreover in altering them the historical context – apparently Three Blind Mice is about Queen Mary I’s bloody persecution of protestants – is lost.

The tendency to bowdlerise children’s literature and songs is part of a wider growing preoccupation with trying to guarantee our children’s safety.

When our daughter started walking, I child-proofed the flat to within an inch of its life.

But as a family friend told me when Maya was first born, however safe you make your home, children still need to understand the concept of danger so they learn to think for themselves.

They also need the chance to explore, to discover and to develop a sense of adventure – like my grandma, as a young teenager, taking all the kids down to Aberdeen Beach in the summer from 6am until it got dark.

I can hardly imagine letting Maya go off for the day like that with any hypothetical siblings.

Yet, at the same time, I worry we are raising children who are less resilient – and perhaps in turn more prone to mental illness.

Last year, new research found a striking rise in mental health conditions among children and young people in Great Britain.

According to the study by academics at University College London, Imperial College London, the University of Exeter and the Nuffield Trust, in 1995 just 0.8% of 4 to 24-year-olds in England reported a long-standing mental health condition. By 2014, this had increased to 4.8%.

In 2008, 3.7% of 4 to 24-year-olds in Scotland said they had a long-standing mental health condition. By 2014, this figure had grown to 6.5%.

There are undoubtedly many reasons for this, not least, as the researchers suggested, a potentially increased willingness to open up about these issues.

But wrapping our children in cotton wool could also be a contributing factor.

Clearly as parents we have a responsibility to keep them safe – both in the real world and, as I wrote last week, from harmful content online.

What this doesn’t mean is sheltering them to the extent they won’t be able to fend for themselves or cope with what life throws their way.

Surely the best protection is teaching them to protect themselves?

Lindsay Razaq is a journalist and former P&J Westminster political correspondent who now combines freelance writing with being a first-time mum