Dad is crouching down about a metre from the television, his fists poised to punch the air.

“Go on Mo, go on Mo,” he cries repeatedly, more animated each time. Next to him, my mum can hardly bear to look. I, too, am peeking through my fingers.

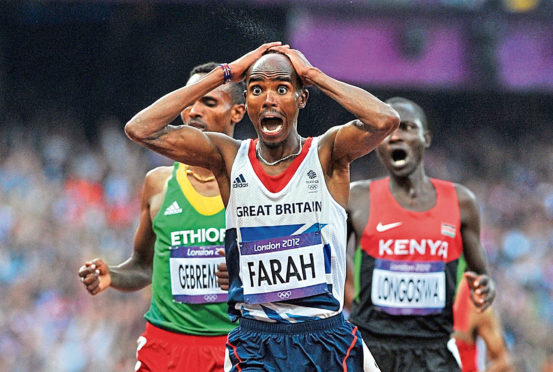

Then it happens. Farah crosses the line to win the 5,000 metres at London 2012, becoming a double Olympic champion.

“Beautiful!” exclaims Steve Cram.

One of my favourite sporting memories, seven years on, I still can’t listen to his final 30 seconds of commentary without tearing up.

I’ve been an athletics nut ever since I watched the legendary Michael Johnson don his golden spikes at the 1996 Atlanta games – when another of my heroes, Usain Bolt, was a mere nine-year-old.

And to this day, every four years, I allow myself to indulge my inner Walter Mitty, and fantasise that there’s still a chance of somehow making it to a games and winning gold for Team GB.

This particular moment transcended fandom, however. It was more than a race. The win – on home soil to boot – united the country in jubilation. We definitely weren’t the only family jumping up and down like wallies in our living room.

Such is the power of sport and that’s why I love it, whether it be the Olympics, the Cricket World Cup or Wimbledon. Especially if there’s a Brit to get behind.

I’ve also always been in complete awe of the dedication and discipline it takes to reach the top of your field and stay there, the ability to push the human body to the limit, to get the absolute best out of it, the strength to find that little bit extra when the highest prize is at stake.

My interest was piqued therefore when I read this week that scientists have calculated the ultimate limit of human endurance.

After analysing extreme sporting events such as the Tour de France and a 3,000-mile ultra-marathon, researchers at Duke University in the US put the cap at two and a half times the body’s resting metabolic rate, namely the rate at which it burns energy when at complete rest.

Or 4,000 calories a day for an average person.

Anything above that, they concluded, is not sustainable in the long term because the body cannot process enough calories to maintain a higher level of energy use.

For instance, marathon runners might go far beyond their resting rate in a race, but this cannot continue over a prolonged period. Eventually, the rate levels off.

Interestingly, the study, published in the journal Science Advances, also determined that during pregnancy, a woman’s energy use peaks at 2.2 times her resting metabolic rate – close to the maximum.

Thus, it seems, expectant mums are living at nearly the limit of what the body can cope with.

I’ll be focusing on this on Sunday when I set out on a charity 10k I signed up for in support of Dementia UK and Friends of the Neuro Ward after watching some world triathlon coverage a few months back.

It’s not quite the Olympics, even if it is taking place in Victoria Park, a stone’s throw from the London Stadium. Nonetheless, it’s a chance to test myself, to be the best I can be.

It won’t be easy and my performance is unlikely to be Mobot-worthy, I’m afraid, with no brilliant time on the cards. I’m not as fit as I was before having Maya – far from it.

Moreover, even finding space for training sessions in a packed schedule has been tricky, never mind the actual exercise. But I’m confident of rising to the task at hand.

Because being pregnant for nine months – my stint as an apparent endurance specialist (that will never get old) – made me tougher mentally. It taught me how to dig deep.

Looking back on how hard it was, although the experience is clearly different for everyone, these new findings don’t surprise me.

Let’s remember for a minute that the process involves growing a small human from scratch, and you carry on with most of your normal activities for the majority of it, which in my case, included covering the 2017 general election.

So, with all that in mind, some might find it patronising to be told that being pregnant pushes the boundaries of human endurance.But I think the comparison to elite athletes is in fact an extremely helpful one, because it conveys explicitly, and in terms everyone can grasp, the extent of the challenge that is carrying a baby for nine months – not to mention the giving birth part at the end of it all.

Yes, women have been doing it forever, but that doesn’t mean it’s necessarily instinctive.

Nor does it mean you are prepared for it or know what to expect because, for you, it’s the first time, and just as no two women are the same, neither are two pregnancies, so the second or third time around might be completely different.

What I’m trying to say is that a woman’s achievement in delivering a child, whatever the circumstances, shouldn’t be taken for granted or underestimated, but celebrated and admired – even if there’s no medal on offer.

To quote a certain prince who recently became a father for the first time: “How any woman does what they do is beyond comprehension.”

Lindsay Razaq is a journalist and former P&J Westminster political correspondent who now combines freelance writing with being a first-time mum