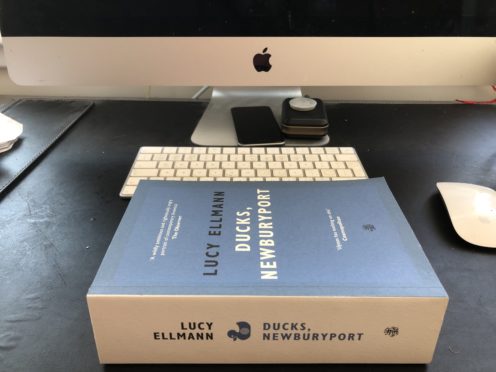

Before me on my desk sits a murderous object. It is a beefy blue brick, a squat sharp-edged slab which, were I to bash one of my many enemies on the head with it, would undoubtedly put him down and leave him there.

This is assuming I could raise it high enough, for long enough, to deliver the blow. Because while I am no weakling, neither am I Geoff Capes or, say, a Hemsworth.

The stout weapon in question is in fact a book – indeed, a publishing sensation. “Ducks, Newburyport”, by the writer Lucy Ellmann, is a monster of a novel, in every sense. Weighing in at 1,000 pages, it is a genuinely heavy piece of kit. It consists almost in its entirety of a single sentence, the rambling internal monologue of an unnamed housewife in Ohio. It has a further 25-page glossary of the many, many acronyms used throughout, from CAPTCHA (Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart), to WWRJD (What Would Republican Jesus Do).

So when I say ‘Ducks…” requires some serious muscle, I mean it – both in the act of holding the thing in your wilting, non-Hemsworth arms, and in the grey matter needed to plough through its dense, relentless, stream-of-consciousness prose.

Flipping at random, here’s an example of that prose: “…blueberry crumb pie, raspberry, huckleberry, boysenberry, strawberry and rhubarb pie, persimmon, sour cherry pie, mock cherry pie, linzertorte, pear pie, apricot pie, Eskimo Pie, the fact that Eskimos never made Eskimo pie, I don’t think, Inuit ivory duck, walrus, narwhal, the fact that Phoebe had an Eskimo doll, what was his name…’ And on and on (and on and on) it goes.

I suspect you’ve quickly fallen into one of two camps: either “I would rather clean the stains from Boris Johnson’s sofa than read this rubbish”, or “this is the kind of wordy Everest I like to scale!” And fair play to you, whichever way you swing.

Me, I’m something of a literary masochist. I like novels that hurt, that confuse, that ask too much – not all the time, of course, but when I know the endurance test is worth it. The critics say “Ducks…” is worth it. The chap in the Sunday Times rates it as “stuck between insanity and genius… I toiled through it, yet missed our heroine afterwards, which might show Ellmann’s brilliance… or just be an example of Stockholm syndrome. To put it another way, you’d have to be mad to read this book, but you might be glad you did.”

Count me in. There’s something heroic about tackling a work of such mammoth proportions, that is so wilfully reader-unfriendly, in which the author has resisted compromising their vision with basic common sense or market reality, has simply refused to stop typing.

I’ve a track record with difficult doorstops. The fierce old Russians demand your time and your concentration; David Foster Wallace’s mad, brilliant Infinite Jest is an infuriating joy; Robert Musil’s great, unfinished The Man Without Qualities captivated me. In fact, the only literary whopper that has beaten me (so far) is Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Unconsoled, which is without plot, or narrative, or logic, and which I’ve set aside twice, having made it about two-thirds of the way through, for fear of my sanity. But then many regard it as his finest achievement, and he was given the Nobel last year, so what do I know?

I have a friend who refuses to read any book more than about 150 pages long, and there is something in that. There’s a special thrill when a great writer condenses their art into a short novel, or a short story. And it saves the hard-pressed punter a fair bit of time.

But there is also much to be said for the challenge of length. As a reader you learn much about yourself as you take the strain, as you plough stubbornly on, not entirely clear if you’re enjoying yourself. The application required, and the rhythms of long works, do interesting things to the brain. The sense of satisfaction upon completion must be a little like breasting the tape in a marathon, but without the blisters.

The other case for length is that it confronts one of the more worrying trends in our culture: the shrinking of the attention span, the need for immediacy, the mental sugar rush of quickfire social media. As Philip Roth put it towards the end of his life: “the concentration, the focus, the solitude, the silence, all the things that are required for serious reading are not within people’s reach anymore.” The ability to sit still and give ourselves over to words on a page for hours at a time has a value beyond the story we’re reading. It has consequences for deeper thought, for inner reflection, for consideration of the broad scope.

Let’s not be too stuffy about it. Sir Walter Scott was an advocate of “the laudable practice of skipping”. There are occasions in many longer works where the longueurs set in and where little is lost by jumping ahead a page or two. Perhaps the effort is the point. As George Mallory responded when asked why he climbed Everest: “because it’s there.”

Chris Deerin is a leading journalist and commentator who heads independent, non-party think tank Reform Scotland