The north-east of Scotland is home to an unmatched heritage of music, song, and story, history and folklore, and the creativity of the people who live and work here.

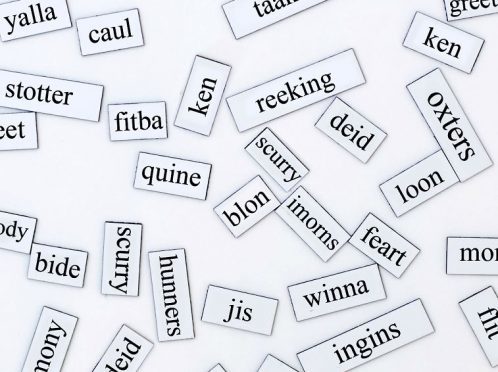

A significant part of this inheritance, and one which runs through all the others, is north-east Scots, often known as ‘Doric’ in the northern and western parts of our region, and by many other names as well – Mearns, Toonser, Aiberdeen, Fisher Doric, Buckie, oor tongue, spikkin, and more.

For well over a century, North-East children arriving in school would be taught, and at times coerced, to ‘talk’ as opposed to ‘spik’.

In Doric:

To ‘spik’ meant to use the language of family, hearth, and home, while English was thought to be the way to get ahead in the world.

This language of home and family is part of people’s character, world view, and wry sense of humour.

But it is less used in the more formal walks of life and we don’t hear enough north-east voices in the media, in civic life, and in our schools.

But the language of home, it turns out, is what’s needed for real progress, and real progress is not just about exams and university.

No, real progress is raising children who have confidence in themselves, their language, and in their communities.

How can that be achieved? Studies in a number of countries have shown that teaching children in the language of their homes increases confidence and, more than that, increases overall attainment in maths, English, and others.

Build a confident child and success will follow.

For a long time, our language has been thought of as only suitable for home and playground, but before that, it was an influential tongue, in court, literature, and international affairs.

Our own Bishop William Elphinstone, founder of the University of Aberdeen, communicated in Scots, Latin, and French during his time in Paris.

The 2011 Census tells us that for than 1.5 million people report themselves as able to speak Scots and the percentage rose to 49% in the north-east, with a majority in some areas speaking Doric/Scots.

Our region is truly a heartland of the tongue.

It’s time to put our language (back) into all areas of life. It’s not about bringing back old words we no longer need, but rather using our own tongue – and the ways of thinking that go with it – in places we’ve been conditioned not to.

Why are there not more north-east voices in the media? Why do we not use it in business meetings and more in civic life?

We all know people who use Doric at work, but as soon as the setting is more formal, years of pressure kick in and English prevails.

At the Elphinstone Institute we’re working with partners to bring the tongue to the fore, aiming to help people embrace their language and use it in any walk of life.

You cannot be what you cannot see (or hear), so we have to give the language more of a presence in the media, use it more in education, and get more recognition and support from government.

In trying to change thinking and policy, there are many lessons to be learned from Gaelic’s successes.

Gaelic activists have made dramatic progress through both grass-roots activism (starting with pre-school and on up through secondary and tertiary education), and campaigning for a broadcast fund.

These must be our ambitions as well. Alongside campaigning, we’re building a ‘Pathway for Scots’ to make it easier for teachers to find stories, songs, and poems closely tied in with the curriculum, and we’re working with a few primaries to pilot the use of Doric as an official language of the school.

At Banff Academy, the Institute’s Claire Needler is working with teacher Jamie Fairbairn to look at how young people are using Doric in social media – and they are – and assessing whether doing the Scots Language Award national qualification has a good effect on overall attainment.

Fairbairn, a man with a great passion for the subject, has seen that for many of the pupils, having the chance to work with and write in their own language can help them excel, giving a real boost to their confidence, which brings rewards in many other areas of their lives, as well.

Other language work includes bringing together teachers with an interest in the tongue, exploring what they need and working with the Doric Board (a constituted development of the North-East Scots Language Board) to raise its profile in the public eye and to support community groups who want to make a difference.

(The Doric Board is offering small grants for Doric-related projects; see the website, www.doricboard.com, closing date December 12)

But Doric is not just for native speakers. In fact, some of the best pupils doing Scots/Doric at Banff Academy are from outwith Scotland and they’ve picked up the language in no time at all.

Language is a great way to build bridges across communities and with people from other parts of the world.

Our evening classes on building language confidence have been a great success, too, with folk from Australia, France, and Luxembourg taking part.

We had to double the number of classes to fit them all in.

The Institute’s LEADER-funded Home-Hame- Дом-Dom project, running in Peterhead, Fraserburgh, Banff, Macduff, and Turriff, is a brand-new project looking at what it means to be home, or far from home.

The aim is to bring communities together, newcomers and longtime residents, to do creative work, from crafts to storytelling and song.

You might ask why this matters, but everyone’s language and cultural roots are central in building pride in who you are and where you’re from.

With globalisation, people all around the world are reconnecting with their roots, building social resilience, freeing creativity, and supporting economic growth, as well.

And with that solid foundation, people take confidence with them wherever they go.

Tom McKean is director of the Elphinstone Institute, University of Aberdeen