In a poem once voted the nation’s favourite, Jenny Joseph contemplated the delights of pensioner freedom. “When I am an old woman, I shall wear purple, with a red hat which doesn’t go and doesn’t suit me,” she wrote in Warning, before listing exploits for the elderly that are more in keeping with Just William than granny gangsters – pressing alarm bells, picking flowers in other people’s gardens, learning to spit.

I don’t recall her genteel ditty including attacking an intruder so hard with a table that it broke, pouring shampoo in his face, and beating him with a broom before calling him an ambulance – but maybe it wouldn’t scan.

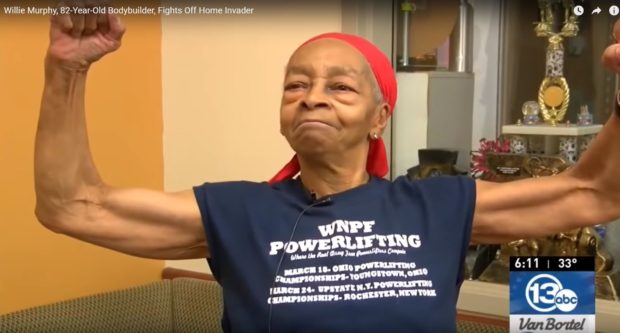

Enter 82-year-old Willie Murphy, a female bodybuilder from New York who set about a 28-year-old male who broke into her home. Reluctant as I am to applaud violence, I couldn’t help silently cheering Willie’s chutzpah, and the way she smashed not just the table, but the stereotypes of old age. It makes me feel quite nauseous when I hear people who have lived full lives having their personalities sucked out of them by those half their age, who adopt the same tone for pensioners that they use for infants in bibs and bunches. Willie was having none of it. “I’m alone and I’m old but guess what?” she said. “I’m tough.”

Our society is messed up. We make a fetish out of youth, and view age so negatively that every positive attribute that passing years can bring a person gets disregarded – experience, wisdom, patience, a sense of proportion. Not only, though, do we ignore the real attributes of older people, we endow them with phoney benign qualities that fit in with a sugar-and-spice-and-all-things-nice caricature.

When my mother was dying, the hospital consultant told me what a privilege it had been to look after such a sweet old lady. He was being nice so I smiled a watery smile, but I did wonder, since she’d essentially been comatose for the time he knew her, what he was basing his character assessment on. Listen, I wanted to say, my mother was lots of fabulous things. Funny, feisty, kind, articulate. “Sweet” seriously wasn’t one of them. If she had been herself, she could have swallowed him up whole and spat his stethoscope out like an orange pip.

The trouble with this granny fantasy is that like all fantasies, it’s kind of lacking in the reality department. The elderly have to be supine and benign and above all silent, because the way our society is going, anyone who wants anything from us is just too much of a damn nuisance. Hence, Age UK this month highlighted the fact that in the last 18 months, there have been 1,725,000 calls to social care by older people for help, care and support that have gone unanswered. 74,000 older people, it says, will have died between the 2017 and 2019 elections waiting for care. That’s 81 a day. Or three an hour.

The irony is that we consider ourselves so sophisticated. We are one of the world’s most prosperous countries – though I suspect the writing is on the Brexit wall with that one – but when it comes to looking after our elderly, we are non-starters compared with countries such as Japan, where the elderly have traditionally been revered, or India where there is a social stigma attached to putting your loved ones in care homes, or China where parents can sue their children for emotional and financial support, and companies are required to give time off to visit parents. France passed a similar Elderly Rights Law in 2004, requiring citizens to keep in touch with geriatric parents, because it had one of the highest pensioner suicide rates in Europe, and because in the 2003 French heatwave, most of the 15,000 victims were elderly and had been dead for weeks before being found.

But how sad that a combination of circumstances – an over-zealous work ethic that refuses to acknowledge a healthy balance in life, and a society that upholds “me” over “we” – results in people having to be instructed by law to do what should come naturally.

It was touching to read recently about an Albanian grandmother who died in an earthquake near Tirana, shielding her grandson with her body. It was the kind of selflessness that seems to come more naturally to the old than the young and which, so often, is not repaid. There are so many signs that we are getting it wrong when it comes to our elderly. The proportion living in poverty has increased fivefold since 1986. Then there’s the fact that half a million people with Alzheimer’s will now have to pay for a television licence, or risk losing one of the lifelines that reduces their isolation and keeps them connected in some small way to what is going on in society.

Alas, the young don’t always get it. And therein lies the poem that Jenny Joseph didn’t write. Warning – to be old and wise, you must first be young and silly.