Earlier this month, I attended the unveiling of a major new artwork in a museum of religion.

I’m not an art buff, so it isn’t something I do on a regular basis. Neither am I a particularly religious person. However, this particular piece of art was a reminder of a major incident in my life.

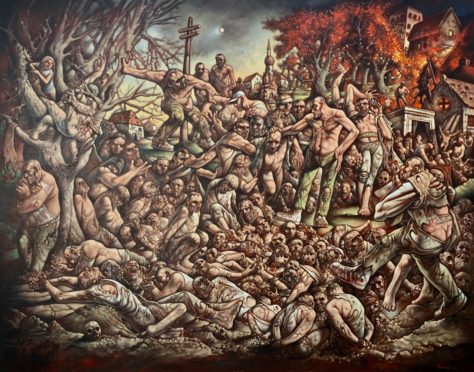

I was at the St Mungo Museum of Religious Life and Art in Glasgow for the unveiling of a painting by Peter Howson entitled “The Massacre of Srebrenica”. The huge painting, commissioned to mark the upcoming 25th anniversary of the massacre, is on loan to Glasgow Museums for an initial three-year period.

Peter’s involvement in the Balkan War began in 1992 when he was commissioned by the Imperial War Museum to record the conflict. The following year, he was appointed official British war artist for Bosnia. The appointment, and in particular the experience of witnessing the aftermath of the Srebrenica massacre, was to have a profound effect on his life.

“It is difficult to put into words the horror of the massacre of over 8,000 men and boys in the town of Srebrenica during the Bosnian civil war,” he said. “I witnessed what I can only describe as hell on earth. The experience caused me many years of illness and the break-up of my family.” He added that he still had memories too painful to talk about. “But I find that painting these terrible events helps me to try and understand why we do such evil things to each other.”

The reason for my interest in the painting was that I too was in Bosnia at the time of the massacre in 1995. As a journalist, I had travelled to the war zone with a convoy of emergency supplies organised by Edinburgh Direct Aid, following an appeal for food, clothing and other necessities by The Sunday Post. Readers rose to the challenge and soon there was enough aid to fill several lorry-loads.

To say the journey from the coast at Split in Croatia through the mountains to Tuzla in Bosnia was interesting would be a serious understatement. Sarajevo was still under siege from Serbian forces, so we had to take the convoy of lorries over unmetalled mountain tracks, with hairpin bends, often teetering over huge drops. The journey took several days, with brave volunteers sleeping in the trucks at night. We were stopped at regular intervals by armed militia, and when we finally arrived at Tuzla, we were wakened early in the morning by a shell, fired from Serb positions outside the town, which whistled over our heads and exploded, thankfully, some distance away.

Stories abounded of the atrocities carried out on all sides of the war. Croats are mainly Catholic while Serbs are Eastern Orthodox. Both cross themselves, but Catholics cross themselves left to right while Orthodox Christians use right to left. We heard that one man hiding in a wood was found by paramilitaries, and told, “You’re going to die, cross yourself.” And it depended on which way he crossed himself whether he lived or died.

The Srebrenica massacre of Muslim Bosnians had occurred just a few days before our arrival in Tuzla, and the news that something serious had happened had already filtered through to the town. Srebrenica, some 100 kilometres south-east of Tuzla, had been designated a “safe zone” by the United Nations, who had stationed a small deployment of Dutch soldiers there to protect it. However, they were unable – or unwilling – to do anything when the area was taken by Bosnian Serb forces under the control of Ratko Mladic, later sentenced to life imprisonment for his war crimes.

An estimated 8,000 men and teenage boys had been taken out and shot and many of the bodies were simply bulldozed into mass graves. Women and children were forced to leave the area, some on foot, others in convoys of buses organised by the United Nations. Many of these refugees came to Tuzla where Edinburgh Direct Aid was distributing supplies. Thousands, perhaps up to 10,000, were forced to live in tented accommodation at the UN air base outside the town. Thousands more came into Tuzla itself, where makeshift accommodation, often just a mattress on the floor, was set up in places like schools.

Unlike Peter Howson, who witnessed the aftermath of the murders in Srebrenica itself, the arrival of the refugees into Tuzla was the extent of my own experience of the massacre. But it was chilling nevertheless. Streams of women and young children – no boys older than around 12 – faces drawn, expressionless. We could only imagine the horrors they had seen and experienced. Food and clothing were distributed, but it felt as if we were barely scratching the surface of the problems the people faced.

In the quarter century since these events, things in Bosnia, Croatia and Serbia have changed beyond recognition. However, it is worth remembering that this wasn’t a civil war in a far-flung third-world country, but in a previously modern nation in the middle of Europe at the end of the 20th century. Srebrenica was the worst atrocity in Europe since the Second World War. As we approach its 25th anniversary we pray that it will be the last.

Campbell Gunn is a retired political editor who served as special adviser to two First Ministers of Scotland