When you are depressed, there can be something alienating about other people’s festivities, especially at Christmas.

The warmth of Silent Night playing softly in the coffee shop; a couple huddled over steaming cups, two forks sharing a rich cake between them; the froth of lights and garlands: all of it becomes an internal ache that serves only to emphasise your exclusion. Perhaps it is the same with love. Perhaps there are people who, when they do not have it in their own life, resent its presence in other people’s.

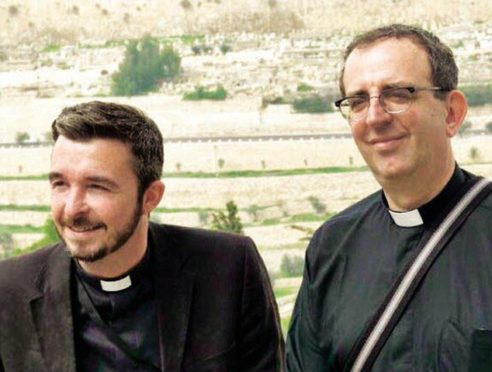

How else can we explain the anonymous letter to Rev Richard Coles, the ex-Communards singer who became a Church of England priest in 2005. Coles has created a whole new category of ‘religious celebrity’, most recently with appearances on Strictly Come Dancing. Sadly, the week before Christmas, he announced that his civil partner, David, also a vicar, had died. A case for empathy you might think, but a stomach churning response from one of his fellow believers began, “’Dear Mr Coles, I can’t begin to tell you how happy I am to hear of the death of your partner…”

David, Rev Coles was told, was in hell – where he would surely follow. Wow. But that’s Christians for you. Is there any judgment quite so self-righteously vicious as religious judgment? Any sanctimony that sings quite as shrilly as that emanating from the hymn sheet of conformity? And no, that’s not the view of an atheist, but a cradle Catholic.

Childhood. Cold stone and cathedral arches. Lilies in the shadows and the scent of incense; red votive lights like eyes in the darkness; candles flickering beneath dimly lit statues. And always the shiver of fear, the shadow of retribution, God waiting for the mistake that would involve casting into the flames. How sad when the catastrophic mistake is called love.

Does it matter who Richard Coles loved? Or just that he loved at all? His loss comes at one of the hardest times of the year, a time when the world expects you to be happy and gets resentful if you are not. Yet ironically, the story of the nativity is not exclusively upbeat. It’s a story of displacement and hardship, of enmity and isolation, of jealousy and misused power. Maybe that’s the story of being human.

In “Church Going”, the poet Philip Larkin mused on who the last believers would be, who would wander curiously, like religious tourists, through the “frowsty old barns” of churches, now empty and smelling of damp. The impulse, he speculated, would be based on emotional impulse rather than rational thought; something that reached a deeper, more primal place than intellect. “ A serious house on serious earth it is,” he wrote, “in whom all our compulsions meet”.

Those compulsions are perhaps the problem. The compulsion to judge. To condemn. To be tribal. To obliterate opposition. Is there a religion on earth which does not have a problem with extremism? In Christianity, there is a tradition of reverence for those who inflict pain on themselves. St Rose of Lima pushed crowns of thorns into her scalp until it bled, wore gloves of nettles, and slept on bricks. Her contemporaries thought she was mad. Maybe they had a point.

The religious instinct for self-punishment creates the conditions – the permission almost – for punishment of everyone else. Reading about Coles while that unlikely combination of Bing Crosby and David Bowie sang, ‘Peace on Earth’ in the background, made the lack of compassion for him particularly poignant. “I have been praying for your pain for some time now,” his correspondent wrote. Sadly, life doles out pain and punishment for us all. We don’t need to create it artificially, to heap it on people because of who they love.

Coles tweeted that poison wouldn’t affect him. “I am, right now, an expert in pain,” he wrote, “the real kind”. Good for him that he can distinguish between what is real in life and what is artificially manufactured; what is God and what is man; what is faith and what is simply venom. At the door of my local supermarket, the mountain of donated food items for the poor is a reminder of the obvious: kindness and tolerance are not confined to churches. The label of ‘Christian’, ‘Muslim’ or ‘Jew’ tells you a lot less than a person’s actions.

Coles, I am sure, must have spent a difficult Christmas, full of bitter-sweet reminders of happier times. Maybe that is the most important part of the human spirit, the ability to seize the sweetness, even when the bitterness is gut-wrenchingly painful. My hope for Coles, and the many bereaved this Christmas, is that they felt not just the sadness of loss, but the comfort of what they had.

To love another person is to see the face of God, wrote Victor Hugo, a message that Coles’ correspondent clearly doesn’t get. Most of us are uncertain about God’s face: if it exists; if we will see it. But if we do, I hope it’s not as ugly as the vengeful face the poison pen writer paints.