It was one of the rare moments in Scottish sport which brought a whole country together.

Think of Jim Baxter and Denis Law at Wembley in 1967, or Allan Wells surging out of the blocks at the Moscow Olympics in 1980.

Or Archie Gemmill waltzing his way past the Dutch defence at the World Cup in 1978.

Such instances are rare for a small nation and they have to be treasured.

But occasionally, the stars align and the fates conspire to create a situation where oval-ball aficionados among God’s frozen people are rewarded for their fortitude and faith.

That was certainly the case in 1990 when the former Five Nations Championship produced the sort of heart-rending conclusion which has become the stuff of legend.

In one corner, England, captained by Will Carling, a man who seemed hyper-confident in his own abilities, produced scintillating rugby throughout the first three tussles of the tournament and their supporters honestly believed they were invincible.

They trounced Ireland 29-0 at Twickenham, thrashed the French 26-7 in Paris and swatted aside Wales 34-6 at the Arms Park with a swagger and a ruthlessness which persuaded one journalist to write: “You could put black jerseys on them and New Zealand would bow in acclaim”.

They had scored 80 points – including 11 tries – in three matches and the bookies stopped taking odds on them winning the Grand Slam. All they had to do was beat the Scots in Edinburgh on March 17 and their magical mystery tour would be rewarded.

Scotland, in contrast, were still undefeated, but had displayed little of the same flair. On their travels, they edged past Ireland 13-10 with two tries from Derek White and narrowly saw off the Welsh 13-9 in a visceral war of attrition in Cardiff.

Indeed, although their 21-0 victory over France sounded convincing, Ian McGeechan and Jim Telfer’s personnel were struggling until Alain Carminati got himself sent off with an act of Gallic bampottery, which saw the flanker banned for 30 weeks.

On paper, at least, it seemed close to mission impossible for David Sole and his colleagues. But, for those of who were living and working in Edinburgh during that period, the excitement and anticipation grew as the showdown loomed.

In bars and hostelries around Rose Street and on the Royal Mile, tickets were changing hands for up to £500. This was in the Dark Ages before email or Twitter, when supporters advertised for these items in newspapers, but demand was overwhelming.

The week before the contest, I interviewed Sole at his work – rugby was still an amateur pursuit, at least in the Northern Hemisphere – and he was averse to predictions. He recognised the challenge would be massive, but his eyes gleamed as he envisaged it.

Then, as that mad March morning arrived, there was a sense of something special in the air on the walk to the stadium.

Gary Armstrong, a giant in miniature, was among those who supped in the incredible atmosphere and the emotional renditions of “Flower of Scotland”.

Some of the T-shirt vendors were flogging items with “England Grand Slam Winners 1990” before a ball had even been kicked. But the home stars – the Hastings brothers, Gavin and Scott, John Jeffrey, Finlay Calder and Sole – used this to their advantage.

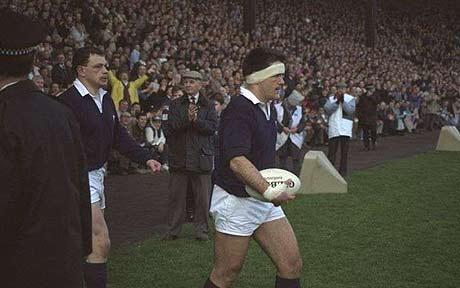

Minutes before the kick-off, they marched out on to the pitch like gladiators, slow, brooding and menacing, even as the crowd unleashed a cauldron of noise.

I turned round and gazed at the late, great Bill McLaren: he looked as if he was teaching a class of kids in Hawick.

And then the first wave of Scottish attacks saw the SRU’s finest establish a 6-0 advantage with two penalties from Craig Chalmers.

Nobody was taking anything for granted against the sweet charioteers, but perhaps the visitors had believed their own hype. True, they cut the deficit with a fine try from Jeremy Guscott, but seemed surprised by the sheer ferocity of the resistance.

At the interval, it was 6-4 and many fans sought out beer, whisky, cigarettes… anything else which might soothe the nerves.

But, almost immediately upon the resumption, they were hollering their backing as Gavin Hastings broke free, kicked the ball ahead while being tackled and Tony Stanger scored the try which gave the Scots some daylight.

I have been in plenty of daunting auditoriums since then – including the 1995 Rugby World Cup final in South Africa and the 2000 Olympics in Sydney – but I have never heard anything more raucous or evangelical than in that corner of Edinburgh.

Some people subsequently claimed that such factors as politics and the poll tax had been instrumental in rousing the Scots to controlled mayhem.

The more likely explanation was that Telfer, McGeechan and many of the Scottish stars had been on the previous summer’s Lions tour to Australia and knew their opponents and how best to probe their weaknesses.

In which light, although the English kept charging, they had no answers. At the finish, they weren’t New Zealand, but they were definitely all black – and blue.

Nothing has equalled that afternoon from 30 years ago. Carling & Co might have gained ample revenge by winning the next 10 matches between the countries.

But this was still the sweetest afternoon in Scottish rugby history.