Such commemorations as might be held shortly to mark the 700th anniversary in April of the signing of the Declaration of Arbroath may well appeal mostly to people of a nationalist persuasion.

That’s understandable. Now that Scottish independence is firmly back on the political agenda, it’ll be irresistibly tempting, if you’re in the pro-indy camp, to give another whirl to the Arbroath Declaration’s more stirring passages.

‘We fight not for glory nor riches nor honours,’ declaimed the 1320 document’s signatories, ‘but for freedom alone, which no honest man gives up except with his life.’

‘For as long as a hundred of us remain alive,’ they affirmed, ‘we will never on any conditions be subjected to the lordship of the English.’

As sentiments of that sort indicate, the hard-fought struggle to preserve Scottish statehood hadn’t ended with King Robert Bruce’s 1314 victory at Bannockburn. England’s monarchs had still to be persuaded to give up on their planned annexation of Scotland. And the Arbroath Declaration, actually a letter sent to Pope John XXII, was a bid to get the papacy, then Europe’s most influential institution, to give its blessing to the notion that English claims had no foundation – legally or historically.

But the enduring significance of the Declaration goes way beyond its role as a summation of a long-ago Scotland’s case for the maintenance of its autonomy.

Claims as to the Declaration’s wider impact can sometimes get a little out of hand – as when, in 1998, the US Senate pronounced that April 6 (the date on the Arbroath document) was to be known across the States as Tartan Day in recognition of the way that the Arbroath Declaration’s wording had supposedly been taken on board by America’s founding fathers.

Not least because what went on in Arbroath in 1320 was mostly forgotten for centuries in Scotland itself, it’s a bit of a stretch to contend that the men who signed the Declaration of Independence promulgated in Philadelphia in 1776 had any very direct knowledge of what had gone into the Scottish declaration of more than 450 years before.

But the Senate was arguably on to something all the same. The case for American independence, as set out in Philadelphia, rested on the conviction that it was for the inhabitants of Britain’s American colonies, not for Britain’s king, to decide how those colonies should be governed. This notion – that governments, as the American Declaration of Independence puts it, have to be seen to be ‘deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed’ – is nowadays the basis of what’s come to be called popular sovereignty.

And that’s a concept that first starts to come into view in the Declaration of Arbroath. Not so much in those eminently quotable quotes having to do with fighting ‘for freedom alone’ but in something that precedes them.

Having acknowledged that the cause of Scottish independence owed much to Robert Bruce, the compilers of the Arbroath Declaration added this: ‘Yet if he (meaning Bruce) should give up what he has begun, seeking to make us or our kingdom subject to the king of England or the English, we would strive at once to drive him out … and we would make some other man who was able to defend us our king.’

That, in 1320 and for a long time after, was a truly revolutionary thing to say. It posed a very blunt and direct challenge to the prevalent belief that kingdoms were to be run as kings saw fit – the belief that kings, no matter what they did or how they did it, were ultimately answerable to no-one short of God. This is what links, however indirectly, the men (they were all men) who drew up the Arbroath Declaration with those other men who, when drafting America’s Declaration of Independence, were issuing their own challenge to a king, in faraway London in their case, who felt himself entitled to rule over them.

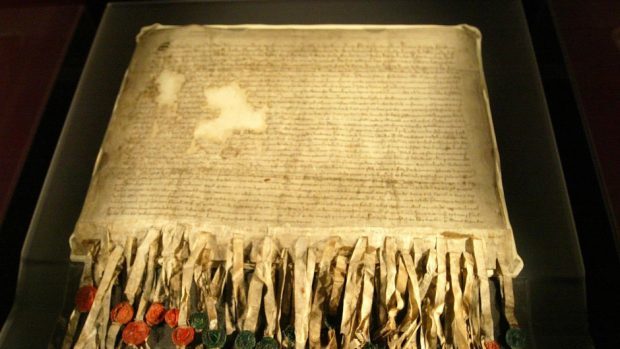

As can be seen from the wax seals still attached to the Declaration of Arbroath, which goes on public display in the National Museum of Scotland next month, it was in no way the work of the Scottish people as a whole. Its signatories – whether feudal nobles or church prelates – would have been horrified by the notion that the generality of Scots should have any input into how, or by whom, their country was to be run.

But by daring to make clear that King Robert, perhaps the most successful monarch Scotland ever produced, was not beyond being reined in or even deposed, these same prelates and nobles took what can be seen as the first steps down the road that led to the beginnings of democracy.

That’s why the Arbroath Declaration is of more than local importance. Yes, it’s a ringing assertion of fourteenth-century Scotland’s right to independence. But it also contains the seeds of the sort of thinking that would one day underpin not just America’s Declaration of Independence but worldwide calls for sovereignty to reside not in kings or queens but in the people.

Jim Hunter is a historian, award-winning author and Emeritus Professor of History at the University of the Highlands and Islands