The baby is going to bring me a present, Daddy. Is it coming soon? How long until the baby’s here, Mummy?

All of a sudden, my toddler’s interest in her sibling-to-be has soared.

We’ve gone full circle. Her initial enthusiasm about the little brother or sister “inside mummy’s tummy”, which was replaced temporarily by obvious insecurity, has returned, and it’s not hard to grasp why.

To be fair to her, Maya does seem genuinely excited to welcome another member to the Razaq clan. But her recent discovery that she stands to profit materially from Baby R Junior’s arrival certainly hasn’t harmed his or her cause either.

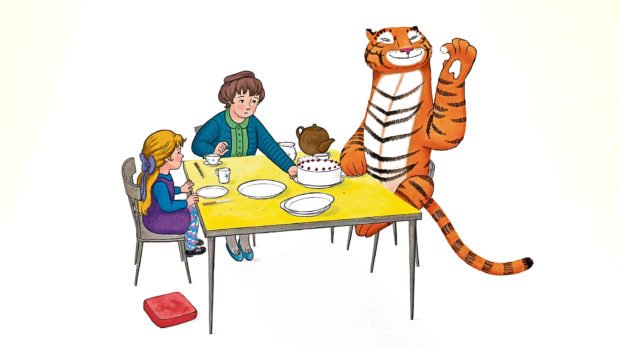

She can’t quite work out the practicalities, though. In fact, I believe she thinks her Tiger Who Came to Tea teddy is tucked up alongside the baby. But for now at least, the details are insignificant. Provided the gift surfaces, preferably sooner than later, she’ll be happy.

She’s not the only one looking forward to the baby’s entrance.

I, too, am finding it difficult to wait – it feels like I have been pregnant for an eternity.

This week brought a helpful warning, however, to be careful what I wish for, that a baby in a rush can make for an experience just as traumatic as one – like Maya – refusing to budge. Maybe more so.

It came in the form of a news story about a baby born on the M5 as his parents travelled to hospital. Not only did Harry take his first breaths on a major arterial route, the lack of a hard shoulder meant delivery occurred in a live traffic lane, the couple’s car shielded by a lorry with its hazard lights flashing. Wow.

Fortunately, he was born safely, but as drama goes, that’s well up there. His father later described delivering his own child as “probably the best thing I’ve done in my life” and I don’t doubt that being so instrumental during those fledgling seconds was amazing. It must have been extremely harrowing too though.

And, because I need something to worry about, the prospect of my little one making an appearance in similarly unorthodox circumstances is playing on my mind.

Of course, my sensible self knows this is more unlikely than likely. Yet social media is overflowing with comparable tales, and within our friendship group alone, there are two couples whose babies arrived at home.

In one case, the process unfolded so fast, the dad didn’t even have time to finish making his cheese toastie. (It never did get eaten…)

Also, I’ve lost track of how often well-meaning relatives have explained that baby number two “always comes much quicker”. Put it this way, enough to prompt me to Google “How to deliver your own baby”. Possibly not the smartest idea at this stage of the game.

And although the scenario might inspire a compelling column, we mustn’t be flippant about the potential dangers in the absence of professional help should things not go to plan – such as when Maya inhaled meconium (the baby’s first stool) while still in the womb.

It doesn’t bear contemplating how different an outcome we could have been facing had expert support not been readily available.

I also want to spare a thought for all the women around the globe who don’t have such easy – or indeed any – access to decent care. Sadly, maternal and infant mortality rates remain high in many countries.

According to the World Health Organisation, every day in 2017 – the year of Maya’s birth – approximately 810 women died from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth. Meanwhile, a report by the Sierra Leone government from the same year, which I came across during my research, gave an estimate of 1,165 deaths per 100,000 live births in the country.

Steps are being taken there to improve the lot of hard-to-reach women. It is hoped, for instance, a new humanitarian drone corridor that opened in November will facilitate the delivery of life-saving blood among other medical supplies.

There’s a long way to go, however, if we are to get anywhere close to rectifying such appalling inequality. Reading of the disparity between my chances and those of my peers elsewhere, the primary feeling is one of guilt. That the place you happen to be born can have such an impact on the safety of childbirth is sickening.

But there’s another emotion – determination not to feel guilty (as I absolutely did last time), about taking early advantage of the benefits that science and modern medicine have afforded us, should the situation demand it.

With Maya, there was pressure – from some of the midwives and societal attitudes more generally – to grin and bear it, tough it out, soldier on without pain relief or intervention. At one point, days in, for example, a concerned Mr R was told off for the mere suggestion I switch to something stronger than gas and air.

“As nature intended” is undoubtedly a noble philosophy that works for many women. But surely the most important thing has to be the health of mum and baby? It doesn’t make you any less of a woman if you have pain relief, an assisted delivery or a C-section – it doesn’t mean you won’t be an excellent mum.

So let’s not demonise advances. Rather celebrate them, count ourselves lucky to live in the age and location we do and put our acquired knowledge to good use.