It was a voice from housekeeping on the line in my Thai hotel room asking urgently: “Mr Knight? Mr Knight?”

This sounded serious.

“Yes, yes, what is it?” I replied.

“It’s about your underpants,” said the voice, with a rising tone of anxiety.

“Yes, what about them?” I replied with a deepening sense of alarm which matched his anxiety.

Mustering a solemnity worthy of the moment he announced: “I am sorry to inform you, sir, that your underpants are broken.”

You might start to wonder if I have taken to wearing some form of mechanically-powered underpants.

Not at all, but it was my first encounter with the hotel’s laundry service – and the tricky task of ironing out translation issues between us.

Damage to undergarments should never be described in the same way as an ornament falling off a shelf, as well you know, but I quickly got his drift.

I worked out that there had been a malfunction.

I was going to tell him to bin them, but feared we might not see any of our remaining items in the laundry parcel again if anything else was lost in translation.

In the same way as the elasticity had parted company with them, I just let go and allowed fate to take its course.

You’ve got to keep a sense of humour when travelling in far-flung parts of the world. It can be surreal and scary.

Especially in Thailand, where the epicentre of coronavirus was relatively close and felt keenly by a nervous government and populace.

A lunatic Thai soldier had also carried out a massacre up the road in northern Thailand.

There is nothing to laugh about in these shocking situations, but surreal humour can play an important role in our darkest hours or when tackling challenges.

Background events around the massacre were ripe for biting satire – the gunman allegedly snapped over racketeering by his own army bosses and their families, who target vulnerable soldiers. This was reportedly about a dodgy deal with his CO’s mother-in-law, of all people.

A few days earlier the Bangkok Post ridiculed the army over a secret memo ordering soldiers to avoid certain body postures in public. The paper’s editorial said army top brass had bigger things to worry about – how prophetic this became.

On the same trip I watched a news video of a father and daughter in war-ravaged Syria joking and laughing in their living room every time a bomb exploded nearby.

They turned it into their personal game, but it was an escape mechanism.

It reminded me of the film Life Is Beautiful, about a father and son joking their way through a Nazi death camp.

Some critics said the subject was beyond humour, but it won Oscars and many other awards for its message.

Death has always been a popular subject for surreal humour.

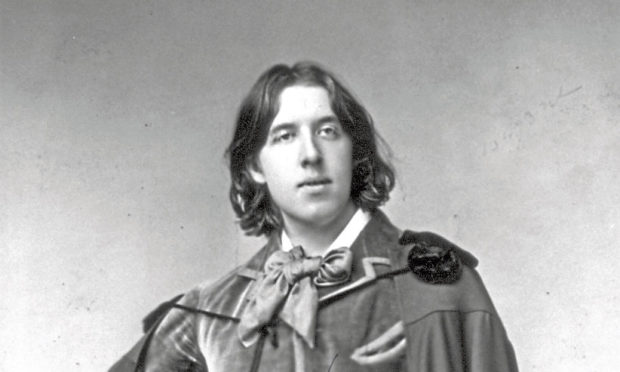

In 1900 Oscar Wilde – on his deathbed in the rundown Hotel d’Alsace in Paris – declared: “My wallpaper and I are fighting a duel to the death. One or the other of us has to go.”

It was 125 years ago this month that Wilde triggered a libel case with Scottish peer the Marquess of Queensberry, which ultimately ruined the playwright.

But Wilde was steadfast in seeing the humour in any situation to make a point – trivialising serious matters while being serious about the trivial things of life.

The saddest thing of all is how some people, who are burdened with a misplaced sense of confidence in their own judgment, take offence over surreal humour.

But how do they miss the signposts writ large? The deliberate ludicrous imagery, illogical juxtapositions and exaggerations which most people understand and accept straightaway as pure amusement and not to be taken seriously.

It is only a mask to help face difficult issues and encourage greater understanding.

There were lots of masked faces as we transited though Singapore.

And coronavirus testing stations, along with official notices that anyone who had been in China in the past 14 days would be thrown out.

We had a pack of masks acquired from Amazon at the last minute, but they were still in the case unopened when we arrived back in the UK.

It was very unnerving. I don’t think I would like to be a customer adviser at Singapore airport either.

We asked directions from one as we searched for our departure gate.

Within seconds an official observer with a clipboard pounced and started asking us if the adviser was any good – so he could fill in an on-the-spot assessment.

The poor chap was only feet away and could probably hear us.

My inquisitor was most insistent about finding out if the adviser was smiling as he gave me advice.

“I don’t know. He was wearing a mask to protect his face,” I answered.

That was not good enough – a box was crying out to be ticked.

“But do you think he was smiling?”

“Come to think of it, I think his eyes were smiling,” I said.

“That’s good enough. I’ll tick the yes box.”

We both laughed as we stood by a testing station manned by grim-faced medics and police. It was a surreal moment.