I was such a silent little girl – I know, what happened? – that contact either with groups of children, or adults engaging in benign child-speak, was agony. Asked years later as a journalist to write about the advice my adult self would give the young me, I understood the pain of self-inflicted silence and boiled it down to three words: “Speak up, girl!”

Voice is important – the ability to express ourselves and be heard. But in recent months, a number of stories have challenged me to think carefully about what “freedom of expression” really means.

We tend to think that to any question, there is a corresponding answer. But sometimes, there is not so much an answer, as an ethical tightrope to walk between two competing alternatives. The tightrope runs through a grey, confusing area and beneath the taut wire, the darkness of an abyss looms. Questions about our right to be heard can fall into that category – freedom one side, censorship the other.

A salutary tale ran recently in the New York Times about a French writer, Gabriel Matzneff, who was hiding out in a luxury hotel on the Italian Riviera when a journalist tracked him down. Matzneff’s history is nauseating – a man who has used his privileged voice as a French literary figure to intellectualise paedophilia, rationalising his sordid abuse of children as if he had been engaged in some kind of consensual sexual encounter.

Matzneff did not hide in his writing the fact that he had lurked outside schools to seduce young girls. Nor did he hide his encounters with prepubescent boys in the Philippines. In his 1985 diaries, “Un Gallop d’Enfer”, or “Racing Forward”, he wrote: “Sometimes, I’ll have as many as four boys, aged 8-14, in my bed at the same time and engage in the most exquisite lovemaking with them.” Weasel words. There is no beauty and no love in the sexual exploitation of a child by an adult.

But however repellent Matzneff’s words are, it is even more disturbing to see his decades-long acceptance by the French elite who did not share his pathology but published it, excused it, even celebrated it.

French president Francois Mitterrand described him as “an impenitent seducer”, and invited him to the Elysee palace. Designer Yves St Laurent paid his hotel bills when he stayed with his underage victims. Literary critics admitted he got a major prize and lucrative stipend because of their “friendship” with him.

How dangerous to confuse talent with a moral compass. Matzneff was handed the freedom card to say what he wanted because he was articulate. He was allowed to legitimise the illegitimate. Had he not wrapped up his pathetic predilections in the insidious words of a literary intellectual, he might have been found in a jail rather than a luxury hotel.

He might yet. Abused children often grow into angry adults and one of his victims, Vanessa Springora, who is now head of France’s Julliard publishing house, wrote her own book, “Le Consentement”, or “Consent”, about Matzneff’s abuse when she was 14. Matzneff was summoned to court for promoting paedophilia. Suddenly, somebody identified the impenitent seducer as a naked abuser.

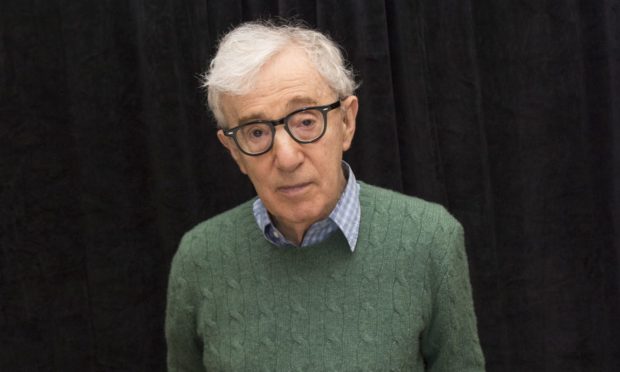

And so to Woody Allen, the one-time darling of American cinema whose daughter Dylan Farrow accused him of sexually abusing her as a child, and whose son Ronan Farrow was a key player in the MeToo movement.

Ronan Farrow published a book with Hachette but was horrified to discover the company also planned on printing Allen’s autobiography. Until, that is, workers walked out and the company backed down, terminating their contract with Allen.

A victory for morality? Or a blow for free speech? In media, we expect different sides of a story to run in the same publication. We don’t need to believe a voice to give it expression, though as a journalist, I want to set that voice in the context of what I believe to be the truth for the reader. It’s my responsibility to give a voice to those who don’t have one. But not any voice, at any cost.

This is not about censoring disagreeable views, but challenging illegal ones. While my first instinct was to cheer Hachette’s workers, I found that I had to think again on Woody Allen. Why? Because I might not like what he has to say but he hasn’t admitted, been convicted of, or promoted, abuse. He has the right to a public defence. His book, “Apropos of Nothing”, has now been published by Arcade and while I might not read it, that’s my choice. But when it comes to Matzneff, I shouldn’t have that choice. No publisher should allow child abuse to have a “normal” voice. Free speech is enshrined in law. But it cannot be confused with the right to say whatever we want, whenever we want. There are no rights without responsibilities – nor, for that matter, responsibilities without rights – and freedom of expression does not entitle us to damage others, whether by sharing bomb recipes, inciting hatred, or promoting abuse.

Silence, I know, can be painful. But expression needs to be responsible, just as much as it needs to be free.