Looking into the future is often a mug’s game.

That thought crossed my mind during my lockdown reading of Nevil Shute’s autobiography “Slide Rule”. Before embarking on the lucrative writing career that yielded books like “A Town Like Alice” and “On the Beach”, Shute was an aeronautical engineer in the 1920s. At the time he was intimately involved with a government drive to develop airships.

As Shute explained, the conventional wisdom was that airships were destined to carry passengers across the Atlantic providing a timetabled service that would offer an alternative to the great ocean liners. The reasoning was that these gigantic hydrogen-filled structures were the only means of delivering air travel on such a scale given the limitations of the aeroplanes of the time.

That vision of the future came to an end in Britain with the catastrophic explosion of the R101, a UK Government sponsored airship which crashed in 1930 over France on its maiden voyage overseas killing 48 of the 54 people on board.

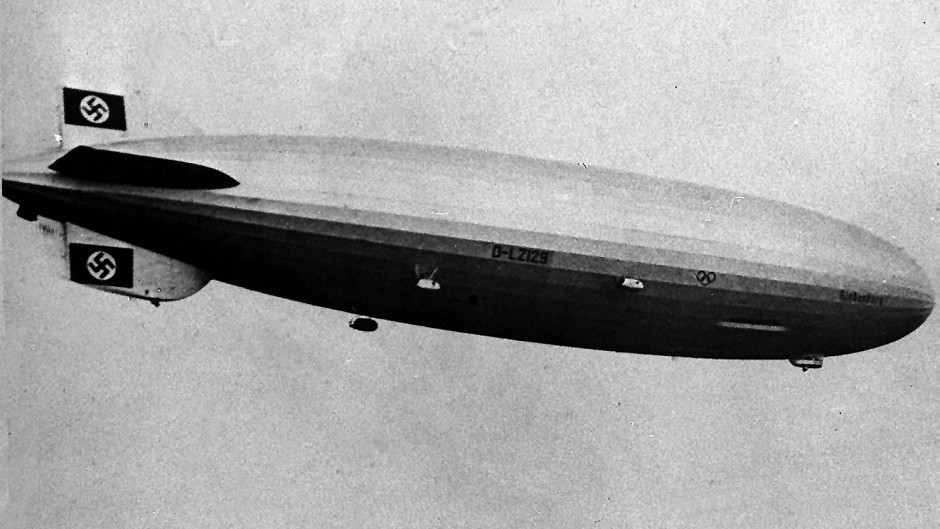

Seven years later the Hindenburg disaster, which resulted in 35 fatalities, sounded the death knell of commercial airship travel and persuaded people that perhaps suspending paying passengers beneath an enormous vessel filled with highly flammable gas was not the way forward.

As history tells us, the 1920s orthodoxy that transatlantic crossings were beyond the capabilities of heavier than air flight proved another botched effort at predicting the future. The rapid advances in aeronautical engineering that were to lead to today’s airliners were just around the corner.

Of course, down the ages there have been numerous examples of bold predictions which the all-seeing eye of hindsight has exposed as utter nonsense.

Ally MacLeod forecast that Scotland had a chance of winning the World Cup before the team went to Argentina in 1978.

Three years later David (now Lord) Steel told Liberal delegates to “go back to their constituencies and prepare for government”, before bombing at the next General Election. Apparently, Albert Einstein said there was “not the slightest indication” that nuclear energy would be a thing. So even the greatest minds can get things wrong.

Thoughts of duff predictions came to mind, because the coronavirus crisis has prompted a lot of crystal ball gazing. These appear to range from the how to deal with future pandemics, how to spark economic recovery and profound questions about the very nature of society itself

Given the shortage of coronavirus tests and Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), inquests into how this crisis was handled are likely to focus on improving supply chains and ensuring the NHS has the capacity to cope with further outbreaks and minimise deaths.

Mitigating the economic damage will also be an enormous part of discussions beyond the essential business of the here and now – preventing deaths.

Moreover, fundamental issues have emerged about the way society is organised. Why should, for example, carers looking after our most vulnerable during the pandemic find themselves on less than £10 per hour?

“The austerity driven response to the 2008 financial crash did not work and worsened the inequality that was part of its cause; we must not repeat those mistakes.”

Scottish Government document on exiting the lockdown

Nicola Sturgeon’s highly praised paper examining strategies for exiting the lockdown gave a strong signal that she believes that this crisis should serve as a catalyst for radical change.

“The pandemic has changed the way societies and economies across the world operate and Scotland is no different,” the document says.

“In some ways this has driven forward changes that we have already been pursuing such as using online tools to reduce the need for travel. In others it has meant radical action to change how we use our NHS or to tackle social problems such as homelessness.”

It also warns that an alternative must be found to the UK Government’s response to the banking crisis more than a decade ago. Then David Cameron’s priority was to tackle public debt by pursuing frugal economic policies – an approach that hurt the most vulnerable.

“The austerity driven response to the 2008 financial crash did not work and worsened the inequality that was part of its cause; we must not repeat those mistakes,” the document warns. “Inequality is also worsening the outcomes for those people impacted by the coronavirus. Our younger people deserve a fairer and more secure economic future.”

This paragraph poses the question of how splashing the cash on a coronavirus recovery can be paid for – a point that was not addressed by the document. With strict limits on Scottish Government borrowing and the Scottish Government’s chief economist Gary Gillespie estimating an “unprecedented” fall in growth of one third, there are no easy answers.

In the past, coming out of crises has proved incredibly challenging. The Homes Fit for Heroes promised after the Great War failed to live up to the rhetoric before the country was plunged into the depression of the 1930s.

The end of the Second World War was to bring about great structural progress including the transformation of the welfare state and the creation of the NHS. But this was accompanied by rationing and post-war austerity.

The aftermath of this virus, whenever it comes, looks set to be dominated by debate on what type of recovery can be built and, crucially, how and if it can be funded. That seems a safer prediction than those made on the future of flight in the 1920s.