In the 15 days since the brutal killing of George Floyd, protests have spread around the world, political tensions have soared, and the issue of race and racism in the 21st century on both sides of the Atlantic has been thrust under the spotlight.

Floyd’s death at the hands of a Minnesota policeman may have sparked the initial backlash, but demonstrators in the US and UK have been provoked by much more. Thousands of people have taken to the streets day after day because of a deep anger over systemic racism in society.

Some have made the argument that we in Scotland are far removed from events across the Atlantic, that the experience lived by black communities under the heavy hand of US police forces or the discrimination in everyday society does not translate here – those on the streets of Edinburgh and Glasgow over the weekend would tell you different.

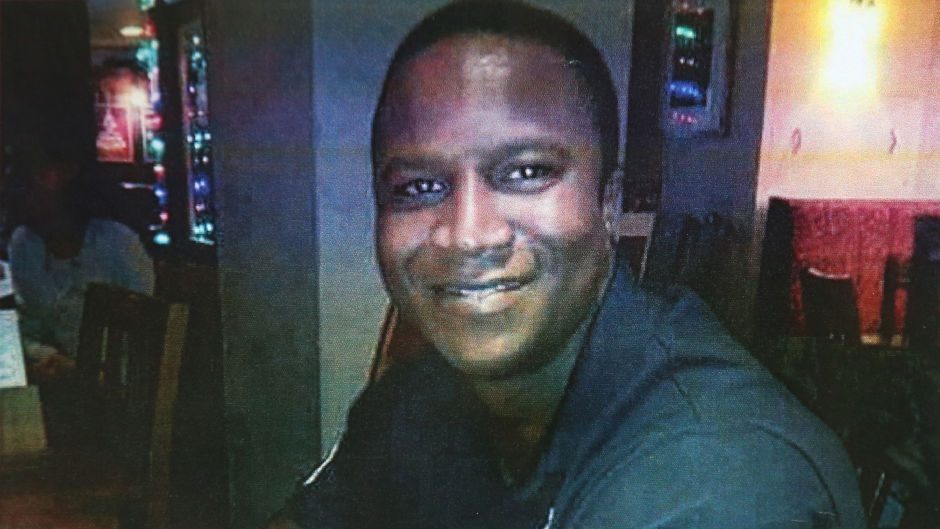

We need to remember that here too, black men lose their lives in custody. In Kirkcaldy in 2015, Sheku Bayoh, 32, died in circumstances with similarities to Floyd. After reports of a man with a knife, police used CS spray, leg restraints and batons to subdue Bayoh, who was unarmed. He suffered 23 injuries and medical evidence supplied by the family’s legal team suggested he died of positional asphyxia, meaning he could not breathe.

Such was the similarity that Bayoh’s sister, Kadi Johnson, felt compelled to speak out over the weekend.

“I could just see my brother, the way he was handled by the police. And it just brought me so much anger and pain, I relived the whole situation again. I was angry and hurt”, she said.

Behind such very personal tragedies, there is also a disturbing set of statistics which shows that black people in the UK are twice as likely to die in police custody, are more likely to be stopped and searched, less likely to be in the boardrooms of top companies and are less likely to be in politics.

This is not just another Westminster problem; in the 21 years since the resumption of the Scottish Parliament, there has not been a single black MSP elected. Exclusions from governance matter, as that is where policy is made and that is how society is shaped.

The current coronavirus crisis has perhaps demonstrated most potently how racism can kill in far less dramatic ways and in far greater numbers.

The death rate among British black Africans and British Pakistanis from coronavirus in UK hospitals is more than 2.5 times that of the white population, according to stark analysis by the Institute of Fiscal Studies.

Why? There is unlikely to be a single explanation, but it has been widely acknowledged that more black Africans are likely to be employed in key worker, public facing roles and are thus more exposed to the virus than those, majority white, people in jobs that can be done from home.

Many will see systemic racism and its consequences in society as perhaps too big or nebulous a problem to tackle, but by breaking it down into smaller issues, progress can be made.

Take education in schools for example. A full understanding of the British Empire and its legacy will give school-leavers and the police, politicians and mangers of tomorrow a better appreciation and awareness of the issues and angers in society today.

It should, for example, be better acknowledged that Scotland was heavily involved in the industries of enslavement that stretched between west Africa, northern America and the trading houses of Glasgow, Liverpool, Bristol, and London. Wealth came into Scotland from these industries — such as sugar, tobacco, and cotton — and Scotland became wealthy because of slavery. When slavery was eventually abolished in the British colonies in 1833, the equivalent of £2.5bn was paid out to slave owners at 430 addresses all over Scotland. Without slavery and stolen wealth, Scottish history would have been very different, and our present would also be very different.

Indeed, the evidence of Scotland’s role is still easily visible today and has been a target for some of the protests over the weekend. In Edinburgh there is a column and statue for Henry Dundas in St Andrews Square. Dundas was a senior British parliamentarian who managed to delay the abolition of the slave trade. There are also streets in Glasgow, such as Buchanan and Glassford, which commemorate the memory of individuals who made fortunes from slave-produced commodities in America. Protesters took the decision to “rename” the streets George Floyd this weekend – but it poses the question, why did it take the death of a man 4,000 miles away for that to happen?

Britain is now a society that 52% of people believe is racist. There are no quick fixes to hundreds of years of oppression, but education and better representation are a start and are urgently needed if this particular virus is to be cured.

Dan O’Donoghue is the Press and Journal’s political correspondent at Westminster