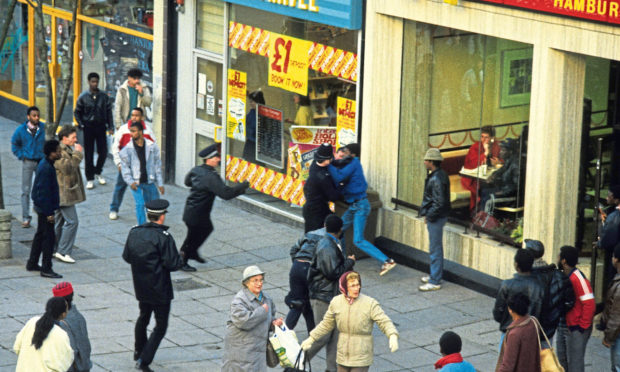

An archive photo of a crowd scene was displayed on my mobile phone and I zoomed in to study one of the faces – yes, it was definitely me. My wife agreed.

I was a lot younger, but the moustache (all the rage in the ’80s) and an oversized grey winter coat clinched it. I remember that neither fitted me very well.

I was one face among hundreds milling around in a street, most looking anxious or angry.

A tragic and brutal incident was about to unleash public anger followed by protest and violent disorder.

Police defended the entrance to a clothing store against a growing group of angry black men who were besieging it.

In this moment, frozen in time, you could see I was transfixed by the unfolding drama. I was a reporter who had just arrived on the scene.

A young black man called Clinton McCurbin was lying dead inside the store after allegedly being put in a stranglehold by police officers.

I was on the edge of an ugly stand-off outside. Word had spread fast. Police relations with black communities in the region had been simmering for months.

The picture does not give any clue as to what I did next, but I remember it vividly. Like any reporter, instinct drove me forward into the thick of it.

Not the wisest move on this occasion as I found myself thrust eyeball to eyeball with a thin blue line holding back the crowd under an entrance canopy.

The atmosphere was explosive.

I glanced up and nodded to a colleague who had secured a good observation point on the upper floor of a shop next door and was staring down at me.

I looked back quickly as a female police officer facing me was responding robustly to one of the crowd raging at her.

Suddenly a fist shot out and smashed her in the face. I was shocked and sickened.

Somehow I dragged myself out of this hell hole in one of Wolverhampton’s busiest shopping streets as fists and batons flew.

Parallels with the George Floyd tragedy in Minnesota have been flooding into my mind. This is why I was looking so closely at archive material on the day of Clinton McCurbin’s death, but did not expect to see myself.

Mr Floyd was asphyxiated by a policeman’s knee, throttling him for almost nine minutes, after being arrested for allegedly using a counterfeit note.

Clinton McCurbin was also asphyxiated in minutes. He was arrested after being accused of using a stolen credit card. The similarities were obvious, but there is a gap of 33 years between the two events.

So has anything truly changed in the intervening three decades despite layers of gloss from politicians about our “tolerant and diverse” country?

I looked at revealing university research into public attitudes in the US after violent anti-racist protests against white supremacists.

It showed anti-racists suffered more in terms of public disapproval after being infiltrated by violent extremists. It was expected of the white supremacists, but not them.

If people wonder about its relevance to Scotland, intolerance and prejudice have no borders – as recent violent and racist scenes in Glasgow showed.

About 18 months before Clinton McCurbin’s death I covered a riot in the black communities of Handsworth in Birmingham.

As we stumbled late at night over piles of rubble, and passed overturned cars and buildings in flames, I remember saying to a colleague, “This is more like Beirut”.

It was a reference, of course, to the shocking state of Lebanon at the time. We passed a burning post office. We didn’t know that two brothers who ran it were dead inside.

We edged into another street and a rampaging mob were all around us. We were scared and trapped. We shielded ourselves near a house. Suddenly, the front door opened and a hand beckoned us in.

An Asian family offered us safe refuge from the riot outside.

There was something almost Biblical about it: Just like the Good Samaritan who helped an injured man from another religion whom he was conditioned to regard with contempt.

We were in their home for some time, hearing shrieks and things smashing outside and doors and windows being battered.

The storm gradually passed into another street and we slipped quietly away in the dark.

I was indebted forever to these warm-hearted strangers who rescued us in desperate moments.

The milk of human kindness, a phrase created by Shakespeare, can be found in the darkest stories.

But their tolerance and exemplary behaviour, and that of many others today, was trampled underfoot by those who hijack legitimate “justice” protests for their own violent ends.

Toppling or even “defending” statues, might seem like exercising democratic freedoms, but taking the law into their own hands actually chips away at them.

The old picture was a warning from the past, but one which is still being ignored.