In the crisp sunshine of an autumn morning, the Perthshire town of Dunkeld seems suspended in time.

The layers of its history are evident in the market place – the ancient cathedral, 17th Century “small houses” restored by the National Trust, the elaborate stonework of the neo-gothic Atholl Memorial Fountain.

Then there’s a more recently redundant artefact of history, a bright red telephone box. Except it is no longer redundant. Inside, shelves are piled with food contributions, tins of soup, packs of pasta, the floor stacked neatly with toys and books. “Community larder”, says the sign.

There is something very moving about seeing, rather than simply reading about, the larder. Perhaps it’s the carefully tended order of it, or the kindness of the notice that says if you are struggling in these difficult times, please help yourself.

Perhaps it’s the notions of decency and communal trust that make it so humbling.

Margaret Thatcher once dismissed the notion of “society”, but it seems the obituary was premature.

Interesting that during this pandemic, when the word “isolation” has never been more used and people are frightened of what they might catch from others, there is a simultaneous acknowledgement of community and the ways in which our lives, our survival and our happiness are interconnected.

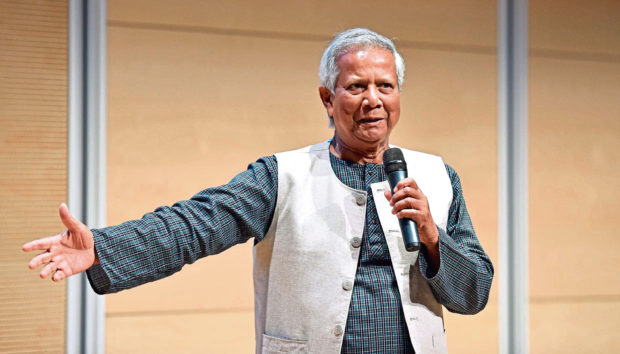

As tighter restrictions loom, most long for “normality”. But a recent interview with Muhammad Yunus, the Bangladeshi-born social entrepreneur, banker and economist who won the Nobel Prize for Peace in 2006, reminded me that while we think this new world is frightening, the old one was also terrifying.

It was a world about to implode because of global warming and wealth inequalities. At least now we can rethink, says Yunus. “We only had a few years left before the whole world collapsed.”

Near the top of the list for redesign must surely be the pharmaceutical industry.

There has been something quite disgusting about the way a coronavirus vaccine has become a capitalist race.

Trump’s attempts to use muscle power to bag it faster for America have merely highlighted the reality that poor countries often cannot afford the pharmaceutical solutions to their population’s health challenges.

If governments funded the industry internationally, using knowledge for the benefit of humanity rather than corporations, the red telephone box metaphor could be extended to include a community first aid box.

Can’t do it? Naïve economics? If there is one thing Covid has proved, it’s that many economic “impossibilities” were possible.

But even before Covid, Yunus turned apparently unassailable institutions – such as banking – into something more malleable. He invented “microcredit”, giving loans to entrepreneurs too poor to qualify for traditional loans from corporate banks.

Bill Clinton once said he wouldn’t stop talking about Yunus until he won the Nobel prize for economics. But the old world revered profit over people.

Yunus argued entrepreneurs need two businesses – one making profit for themselves, one making profit for others. So, maybe it was fitting that he got his prize for peace. It illustrates an important truth in life – there will never be peace without equality.

During this Covid crisis, we need to be at our most daring in looking for solutions. New ways of thinking lead to new ways of being.

Yunus was once voted number two in the world’s top 100 thinkers and interesting thinkers turn things on their head. You look into the kaleidoscope in their minds and suddenly, the pattern you see shifts and reforms, making a different picture in your own.

Yunus’s Grameen (or “village”) Bank worked on the principle that the poor don’t need to remain poor. His approach did not just overturn financial conventions but social ones: 94% of Grameen Bank loans were given to women in poor countries to give them a livelihood and independence.

The old world is the one we hunger for, but for many it was the one that left them hungry.

The Scottish Government has now called for organisations and community groups to share their experiences of tackling inequality during the pandemic to help build greater social justice in future.

What if we did that globally? Last year, two billion people lacked regular access to food.

In 2013, the World Bank set targets to end poverty in a generation, but currently, 10% of people struggle to meet basic nutrition, health and education needs, or access water and sanitation.

By 2030, it is estimated that 160 million children will still be living in extreme poverty.

Right now, we’re frightened life will never be the same again. But maybe it shouldn’t be. We can do one of two things.

We can cling to old ways or we can rethink and reshape.

And perhaps that’s why Dunkeld’s community larder was so moving. A once-vital community resource was remodelled and given new meaning.