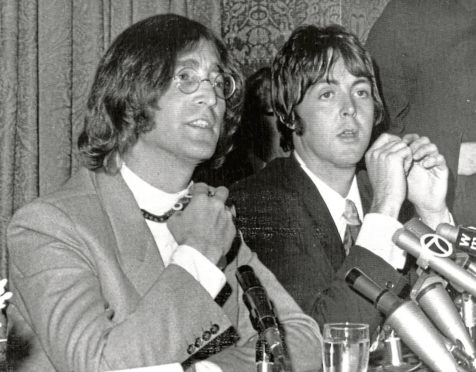

How do you sleep? It’s a question that has long inspired artists. John Lennon unleashed a famous broadside of that name against Paul McCartney following the rancorous dissolution of The Beatles: “The only thing you done was yesterday/And since you’ve gone you’re just another day”.

For the Stone Roses it was a furious howl at music industry manipulators: “I’ve seen your severed head/at a banquet for the dead”.

Sam Smith, who has a song with the title on his forthcoming album, is merely the latest.

Painters and sculptors have been obsessed with the sleeping form through the ages, from Botticelli to Lucian Freud, from Canova to Louise Bourgeois. Dreams and their meanings are a commonplace – if usually tedious – trope in literature, as authors excavate the unconscious mind.

Everyone I know is currently talking about sleep a lot. During this Covid-19 crisis there’s either too much of it or not enough. How are you sleeping, we ask. Friends working from home conk out on the couch most afternoons, groggily waking to the early-evening gloaming.

Others struggle to close their eyes at night, or manage only a few hours of broken rest, and then must drowsily navigate their way through the trials of a new day. Still others see no real reason to get out of bed in the morning. For most, the fabled eight-hour stretch that supposedly leaves us healthier, happier and more productive is an unattainable, retreating continent.

Given sleep’s close relationship with mental health it’s no surprise that these peculiar times are unconducive to rest. “A ruffled mind makes a restless pillow,” said Charlotte Bronte. For me, the assassins of my slumber tend to be lingering problems that lack an obvious resolution or endpoint. Covid is the Villanelle of unresolved crises. Anxieties about money and work, family and friends, and perhaps even the peripheral, grating whine of national and international uncertainties, of Brexit and Trump, affect us too.

Smart people are getting very rich from all this – Big Sleep, as we shall unavoidably call the industry. The global sleep-aid business is worth something like £60 billion a year, taking in bestselling books and TV programmes, specialist mattresses and pillows, psychologists and therapists and hypnotists, corporate experts, pills to knock you out and pills to wake you up,and now apps that monitor your nightly shut-eye like lunar sentinels – delivering a morning report on how much of your sleep was light and heavy, the span of your REM, the moments you woke up, your blood oxygen saturation… they even award you a sleep score: well dozed, my dude!

I’ve always been a lark, while my wife and daughters are owls. As a child, I was an unpopular sleepover guest as I’d wake early and throw things at my snoring pals until they’d participate in whatever 6am enthusiasms had occurred to me.

In recent months, though, I’ve taken things to a ridiculous extent. I’ve begun waking somewhere around 3.30am, clambering out of bed and heading for my study with a large cup of coffee. I log in and plough through emails and documents that require my attention, firing off responses. I catch up with the papers and lose myself in novels. I write articles, sometimes listen to music, even watch the occasional movie. The more eccentric I grow, the more I seem to get done.

It’s not that I’m facing any grave personal traumas that jar me to consciousness. I think it’s that the enforced disciplines of normal life have broken down – the daily commute, the presenteeism of office life, the face-to-face coffees and the working lunches, the evening drinks and events.Pre-lockdown I had a pretty hectic schedule; without all this, without organised chaos, I feel like I’m in the opening credits of Buck Rogers, spinning randomly through the universe.

And anyway, sleep wasn’t always the way it is now. Historically, people would have two phases to their nightly rest. They’d go to bed around 9pm or 10pm, sleep until midnight or 1am and then get up for a couple of hours. They might then go out for a walk, do some needlework, cook or pray or have sex, before going back to bed for their “second sleep”. Researchers say it was only in the early 20th Century that the practice finally became obsolete and the idea of a solid eight hours kicked in. This fascinating culture formed the basis for a splendid recent Robert Harris thriller.

So, as Sam Smith is no doubt crooning on a radio near you, how do you sleep? Are you a small-hours botherer, or a slovenly lay-in? A siesta grabber, or a dawn-greeter, or a red-eyed wreck? Has sleep become more important to you in the past year, as you hide away from grim reality, or less so, amid the formless volatility that comprises so much our current existence? If you’re not quite sure, why don’t you sleep on it?