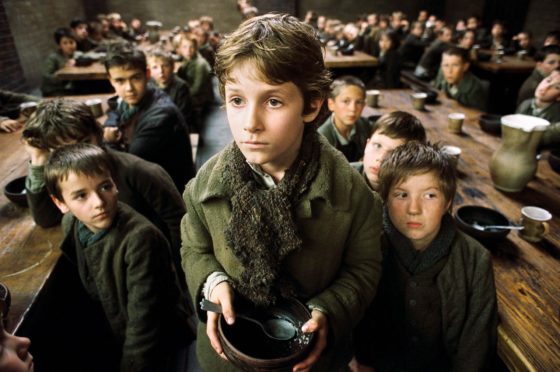

There is something in the tale of Oliver Twist that never fails to satisfy the modern audience, the pathos of the hungry little ragamuffin orphan with his outstretched bowl and pleading eyes, begging for more, Gawd luv ‘im.

Those awful fat cats, bloated with rich food and self indulgence, punishing poor Oliver for daring to be poor and hungry! It elicits a strange, safe nostalgia for Dickensian Britain because fings ain’t like that now. Are they?

Yes, actually. Recent events suggest we still ignore Oliver’s outstretched hand. It’s just that the circumstances of the modern day Oliver are different, his needs no longer limited to a decent sized bowl of gruel. Though that’s not a bad start. In Britain, 2.5 million children are affected by “food insecurity” – hunger to you and me. It’s taken a magnificent campaign by a 22-year-old footballer, Marcus Rashford, to remind us that child poverty is not simply a problem for international aid. Of those children affected in Britain, 10% of cases will be acute – that’s more than double the European average.

Recognising the deteriorating plight of many families during the pandemic, the Scottish government has pledged £30 million for free meals during school holidays. The Welsh and Northern Irish governments have committed too. The UK government, however, has not for England – and we must draw appropriate conclusions about that. But this is about more than food.

Children are like puppies. Cute, and great for advertising. Fairy bubbles, Bisto gravy, Andrex toilet rolls, Dairy Milk chocolate…. There’s nothing like a dimple, a fetchingly skewwhiff nappy or a devoted smile at a pretend parent to shift a few BOGOF deals. It plays into our idealised vision of happy families, charming offspring, and stress-free parenting. It’s not the Fairy, Bisto or Andrex we want; it’s the perfect Sunday roast and the kid who does what they’re told while it’s being served.

And there, as Mr Shakespeare would say, is the rub. For children, like the rest of us, are complex. Sometimes they get a rough deal in life. They get hurt and scared and difficult. Sometimes they get damaged. They don’t smile and say, ‘yes please mummy’ and, ‘I can’t wait to do my homework’. They shout and they sulk and do things they shouldn’t and take things they shouldn’t. But they’re powerless in society and nobody listens to them – and that’s why they need protected.

So it was hard to read two more stories this week of our failures with children. One was a condemnation of the UK government by the UN rapporteur on inhuman and degrading treatment, for allowing children in detention to be isolated for up to 23 hours a day in cells under Covid emergency measures. It would be considered cruel for an Alsatian but maybe as a nation, Brits care more about dogs than kids.

The second was the case of a sixteen-year-old girl who was, according to a high court judge, a danger to herself. She’d been in an adult ward but had threatened to kill herself and staff. No place could be found for her in an NHS child and adolescent mental health psychiatric unit. Mr Justice MacDonald ruled that she urgently needed supervised placement – but he couldn’t give her one. “As of this morning, no such placement is available anywhere in the United Kingdom,” he wrote. The italics were the judge’s, a visible sign of an incredulity the rest of us can only echo.

The transition between adult and children’s mental health services in Britain is quite simply inadequate; a gaping gulf that children are expected to take a flying leap across and try not to fall into the chasm. Plenty of them are having to take that risk. There is a rising tide of mental health problems in young people – an increase of 50% since 2017 – and in any given year 10% of children will be clinically diagnosed. The demands of our complex world mean children need more than a bowl of gruel and a cell to survive.

We cannot always rely on the rarefied atmosphere of the courts to capture the needs of the least powerful, the most needy, the most vulnerable of our society, any more than Oliver could rely on the bloated beadle. But for once, the high court judge put his finger on it, quoting Nelson Mandela. “There can be no keener revelation of a society’s soul,” he wrote, “than the way in which it treats its children.”

Catherine Deveney is an award-winning investigative journalist, novelist and television presenter