Benjamin Franklin is one of the more consequential humans to have graced the planet. Across his 85-year span this revered polymath was inventor, scientist, printer, journalist, politician and diplomat.

He was a Founding Father, helping to draft the Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution. He negotiated the Treaty of Paris that in 1783 ended the American Revolutionary War with Britain. The restless Franklin also found time to invent bifocals, create the first US lending library, open a university, discover the Gulf Stream, help us better understand electricity, invent the life-saving lightning rod and even, during his years in London, design wooden flippers so he could swim long-distance in the Thames.

He was, by all accounts, a good laugh too – to the point he was prevented from physically writing the Independence Declaration for fear he would insert jokes.

On September 17, 1787, the final draft of the Constitution (“We the people…”) was ready to be signed. Franklin was 81, his strength failing, and so asked a younger Founding Father, Fife-born James Wilson, to read his speech. There were several points in the Constitution with which Franklin disagreed, but, he said, ‘having lived long, I have experienced many instances of being obliged by better information, or fuller consideration, to change opinions even on important subjects, which I once thought right, but found to be otherwise. It is therefore that the older I grow, the more apt I am to doubt my own judgment, and to pay more respect to the judgment of others.”

More than most, he had earned the right to trust his own perspicacity. But what made Franklin truly great and fuelled his achievements was self-doubt and an open mind. He understood the fundamental connection between humility and wisdom.

At times over the past four years it has felt like this America was lost forever. Even now, the orange smear left across the floor of the Oval Office as Donald Trump is dragged from the room makes it hard to move on. Is it possible we are turning a corner on this festival of racism and misogyny and greed and ignorance in the most powerful pulpit on earth? As that unimprovably profound Scottish saying has it: mibbes aye, mibbes naw.

Into this turpid scene, like a spring morning, has wafted Barack Obama’s new presidential memoir, A Promised Land. Obama has his flaws, and at times over the years has seemed a bit too delighted with himself (although, why not?). But he closely represents the spirit of Ben Franklin’s America – of humility and wisdom, of self-examination and the search for improvement.

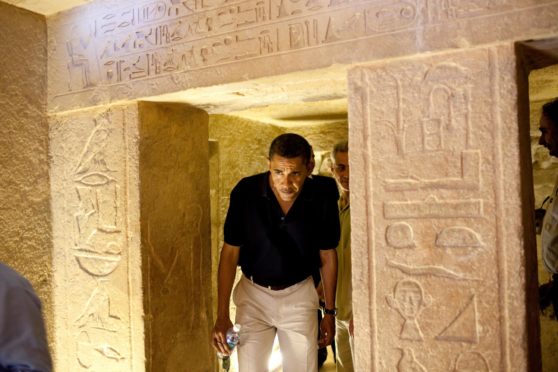

Obama recalls a trip to Egypt where, carved into an ancient wall, he was confronted by a face that resembled his own. He considers the ephemerality of power: “All of it was forgotten now, none of it mattered, the pharaoh, the slave, and the vandal all long turned to dust. Just as every speech I’d delivered, every law I passed and decision I made, would be forgotten.”

In an interview with the Atlantic, he ponders whether one should be a pessimist or an optimist. “What I’ve always believed is that humanity has the capacity to be kinder, more just, more fair, more rational, more reasonable, more tolerant. It is not inevitable. History does not move in a straight line. But if you have enough people of goodwill who are willing to work on behalf of those values, then things can get better.”

Sadly, Downing Street has in recent years preferred to operate on Trumpian principles: state as fact what you wish were true, regardless of evidence; overclaim what you are able to deliver; denigrate and delegitimise opposing views; never apologise, never explain. A kind of person has thrived for whom nothing can shake the belief in their own rightness, not the 2008 banking crisis, not Brexit, not Covid. These events should have revealed to us how little we understood of this world we have created – that not only did we lack the answers, we didn’t fully grasp the questions.

The departure of Dominic Cummings, who treated politics as warfare and other people as chaff, suggests the tone, at least, might be about to change. As Keir Starmer said during a recent appearance on Desert Island Discs: “I started by thinking I had all the answers. And as I’ve grown up, I’ve learned the power of saying, ‘I don’t know, let’s have a look at that’. And that’s been a very important lesson for me.”

We would be a better country if we all learned it.

Chris Deerin is a leading journalist and commentator who heads independent, non-party think tank Reform Scotland