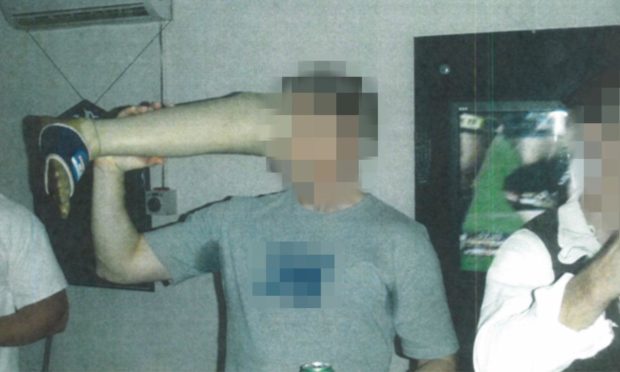

As an abstract image, it is grotesque: a prosthetic leg from a dead man, ripped from his corpse on the battlefield and taken as a macabre souvenir, then used to drink beer from in a makeshift military drinking den.

Were it the stuff of imagination from a writer’s pen, it would be disturbing enough, but the fact that it is the real behaviour of Australian special forces in Afghanistan, revealed last week after a four-year investigation into their treatment of prisoners and civilians, would make any normal person weep for the black soul of mankind.

75 years ago this month, the Nuremberg trials were taking place. Nazi commanders were forced to account for their crimes, but Nuremberg was also the foundation stone of the international court which we adhere to today. It is tempting when we hear about the holocaust to tell ourselves that it was a different age, a period of history that could never happen twice. The rationalisation dampens the communal rush of shame, and the chilling fear of what humanity is capable of, temporarily subsides. We were not part of it.

To commemorate Nuremberg, a short Guardian film has been made that follows a very special journey. Colette is 90 years old, as sharp and feisty as you might expect an ex-member of the French Resistance to be. During the war, tragedy struck her family when her brother, Jean Pierre, was captured and taken to a German concentration camp, Mittelbau-Dora, where he died in 1945, just three weeks before the camp was liberated. Colette had never visited but made a poignant pilgrimage with the aid of Lucie, a 17-year-old would-be historian who worked in a local museum and was fascinated by the documentation of Jean Pierre, and excited by historical detail.

The relationship between the two is touching: tough, yet vulnerable Colette holding the arm of tender-hearted Lucie who, when confronted by the crematorium where Jean- Pierre died is overwhelmed by both the sadness of the dead Jean Pierre, and the sadness of the living Colette, hunched at her side. And looking at Colette, insistently unsentimental about her “brilliant” brother who she was in awe of but claimed she was not particularly close to, it struck me that there are many different kinds of bravery and perhaps the most impressive is emotional bravery.

All her life, Colette refused to cross the border into Germany to face the place where Jean Pierre died, or the nation who took his life. It would, she thought, change her forever. Perhaps at 90 ‘forever’ no longer felt so very long, but it was for the young, the Lucies of the world, that she agreed to go. One minute furious, the next tearful, Colette doggedly persisted with the painful journey and her emotional outpourings, at times almost petulant, were a reminder that anger is not a single emotion but a cocktail, and the biggest component of it is hurt.

In a similar way, perhaps one component of the Australian soldiers’ callousness is fear. Perhaps when soldiers are asked to carry out brutal acts, the only way to do so is to first brutalise their own hearts. But the Rome statute on criminal activities in wartime is clear: war crimes include “outrages against personal dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment”. There is a call for the Australian commanders, who watched the men drink from the prosthetic leg and in some cases joined in, to be called to account.

As Colette and Lucie wept together outside the concentration camp’s crematorium, the young woman and the old came together in their tears for both Jean Pierre and humanity. In the heat of that moment, Colette pulled a ring from her finger and gave it to Lucie. It was Jean Pierre’s and it would be too big for Lucie’s slender youthful fingers, but would look fine around her neck. When Lucie became an old woman of 90, Colette advised, she should look back and remember this moment.

The Nuremberg anniversary invites us to look back too. The advice, often, is to live for the now, but how important it is, sometimes, to look back. The holocaust. The Rwandan genocide. The 1993 Somalia affair, which involved Canadian special forces torturing and killing a 16-year-old boy and led to the regiment being disbanded. Afghanistan atrocities. Memory and anniversary remind us who and what we are. For when you believe the past is no longer part of the present, it so easily becomes part of the future.