I stumbled across something which reminded me of where they kept movie props at Warner Bros Studios in Burbank, California.

It was not quite as exotic or mesmerising, but basic elements were there. A veritable Aladdin’s Cave of odds and ends piled on top of each other. There was a big difference: I was in a hospital corridor in Aberdeen and not an iconic Hollywood studio a few miles from Los Angeles.

While exploring at Warner Brothers a few years ago I admired a props treasure trove whose contents framed some great films. As I leaned on a small sideboard, a guide told me Humphrey Bogart had done the same with it while playing Rick in Casablanca. I jumped back startled as though I had spilled coffee on Mona Lisa.

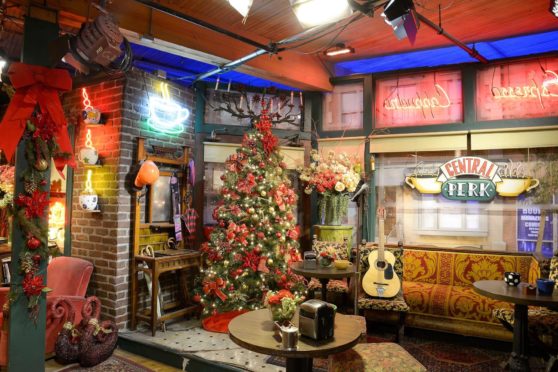

Another guide pushed open a big metal door on rollers like you might find guarding a butcher’s refrigerator. Our jaws dropped: inside was the perfectly preserved set of Central Perk cafe in Friends, complete with famous orange sofa. You could hardly swing a cat in there, but it’s amazing what clever camera work achieved.

Then a studio buggy ride where we came across an action scene being filmed. Overturned cars were engulfed in flames; actors ran around with blackened faces and torn clothing. But they stopped abruptly, turned towards us with smiling faces and waved as we went by.

I was not sure if they really were filming a disaster movie or simply lay in wait for studio-tour buggies, and pretended.

It seemed like a disaster happened here, too, as I snapped out of my day dream in a corridor at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary. I reported to a ward for an investigative procedure I had been awaiting for months. It seemed deserted, as though abandoned in a hurry.

Chairs, tables and other odds and ends were piled on top of each other in what used to be a “patient recovery room”, according to the door sign. Next to it was a lonely waiting room. It was clear nobody waited here anymore. Just beyond was the “Marie Celeste” ward: two rows of beds, but not a patient in sight. Where had everyone gone?

It was as though the place had been under siege from a plague in one of those apocalyptic Hollywood films. That is exactly what happened, but for real as Covid-19 attacked and the NHS defended.

It was a ward for non-urgent day surgery. I know because I found an advert for a nurse’s job from a year ago, which described this as a busy place then. Not anymore, it seemed; maybe the work moved somewhere else. I suspect not as cases were delayed UK-wide to make the NHS fit to fight Covid-19.

Shocking waiting lists for everything from cancer to hip replacements also followed.

I am indebted to a couple of readers who were quick to respond the last time I mentioned this. They begged to differ as their cases were dealt with swiftly, and no delay. I was delighted for them, but this is sadly not the case for many.

The hospital had a weird half-open, half-shut atmosphere, but I was heartened that some non-urgent cases were moving forward at last. It felt like a battleship on standby – ready to clear the decks again at any moment for new waves of Covid-19.

Something stirred at the far end where two nurses were running what looked like a temporary clinic. They were cheerful and reassuring, as I always find with frontline NHS troops. I’ve often heard it said that you leave your dignity and embarrassment at the ward entrance on these occasions. I found an opportune moment to recall this as I stood half-naked with tubes linking me to monitoring equipment.

I was topped up like a human kettle as nurses scrutinised every reaction internally and externally – if you follow my flow. It was like a surreal comedy, but after initial shock it bizarrely seemed as normal as the hairdressers. I almost started talking about my next hols. I departed full of gratitude for their care and professionalism.

On the way out I was delighted to bump into familiar faces: two other nurses who helped me through my prostate cancer surgery in 2018, and this continuing support. Like so many others they were drafted from their own speciality into frontline Covid-19 intensive care. Now they were back. To me they were Hollywood heroines returning from the trenches.

I had an overwhelming desire to hug them. But this was reality, and I couldn’t.

David Knight is the long-serving former deputy editor of the Press and Journal