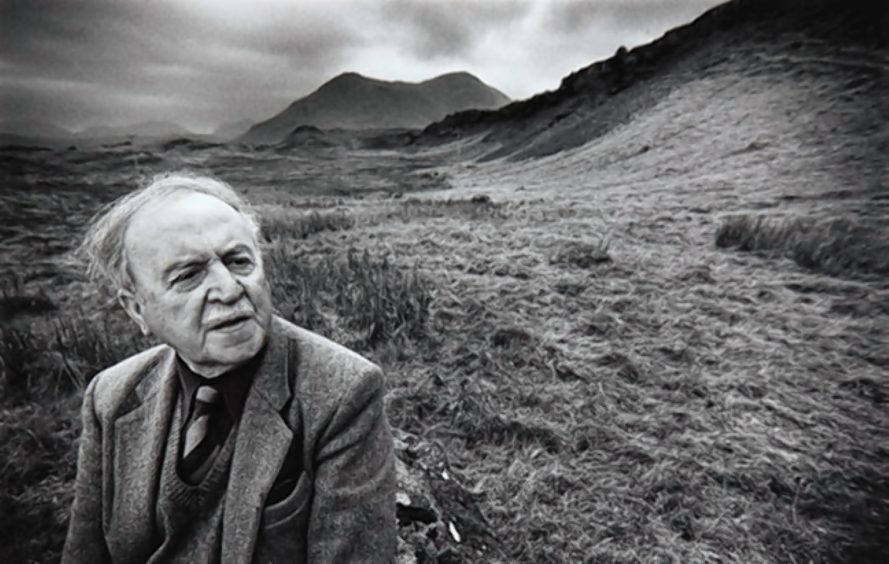

I was in Raasay the other day.

Sorley MacLean’s Raasay, I should say, for every step I walked was filled with the bàrd’s recreation of the island in his poetry. The very place names have less meaning if you don’t know Sorley’s poetry, preferably in the original Gaelic. Baile Chùirn, Screapadail, An Clachan, Suisinis, and of course Hallaig, where the dead have been seen alive.

Literature’s capacity to create a place is remarkable. I was in Paris last year (before the lockdown) and, much as I enjoyed Montmartre and the food and coffee and almond croissants, I spent most time with Balzac and Proust and Zola and Fitzgerald and Hemingway, in the Paris they create every time I read or remember their work.

I didn’t even visit any of the museums dedicated to their lives and works. They are everywhere.

Same with Wordsworth: I’ve been several times to the Lake District in all its loveliness, and yet it’s his lines that carry me through the region. Not so much the daffodils (which you can even find in South Uist) but the wishing gate in the vale of Grasmere and the old Cumberland beggar and the leech gatherer. Oh, especially the leech gatherer, who lives forever up on that lonely moor.

Great literature breathes life into empty spaces

What is it about literature that gives more life to a person or a place or a time than that person or place or time ever had?

I suppose it has to do with that miraculous bit in the book of Genesis where “the Lord God formed man of the dust of the ground, and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life; and man became a living soul”. Seeing that we are all made in the image of God, do we not too reflect that life-giving breath?

What such great literature does is to elevate things to immortality

I think what great literature does is to breathe life into both crushed and empty spaces.

It grants us all honesty, in the long term. Not through platitudes or cliches, but by looking afresh (sometimes with awe, sometimes with anger, sometimes with cynicism, sometimes with despair) at the reality around, and by confronting it. Reimagining it. So that it becomes transformed.

It’s not about the window – but it’s all about the window

Sorley’s finest poem, Hallaig, performs that magic. It begins with the famous, prosaic lines: “The window is nailed and boarded / through which I saw the west”.

I’ve always regretted that I didn’t ask him where the window was. I know fine he’d refuse to answer, for the poem has a much greater purpose, speaking of the window of history and memory and education and faith and hope and desire through which he saw the world, even though there would have a been a specific window that would have birthed the poem. For all our lives are littered with ruins and windows nailed and boarded.

And then, word by word, and phrase by phrase, and image by image, Sorley pinches the nails out and removes the boards so that we can see his love at the Burn of Hallaig, a birch tree, where she has always been, between Inver and Milk Hollow, here and there about Baile-Chùirn: she is a birch, a hazel, a straight slender young rowan.

The whole island becomes transformed and time melts and the dead walk, clear in the mystery of the hills, where there is only the congregation of the girls keeping up the endless walk. So that by the end of the poem the cleared village of Hallaig becomes everything that it ever was or wasn’t, or could be, or will be. It is changed into being.

Can good writing make reality disappointing?

What such great literature does is to elevate things to immortality. It eases you into seeing the possibility of all things, so that Wordsworth’s leech gatherer is forever there, roaming from pond to pond, from moor to moor, housing – with God’s good help – by choice or chance, and in that way gaining an honest maintenance.

There is a danger that where literature has created an image the reality itself will disappoint.

We may go to the Mearns hoping to meet Chris Guthrie, and if we know the work, we will. Because she is there at every peewit’s call, in every breath of wind.

The same as dear Sorley was with me every step of the way last week as I walked through the woods of Raasay to his birthplace at Oscaig, with the girls chumming us in silent bands going to Clachan as in the beginning.

Oh, and Anna Karenina is calling in for a cèilidh tonight. She’s great company.

Angus Peter Campbell is an award-winning writer and actor from South Uist