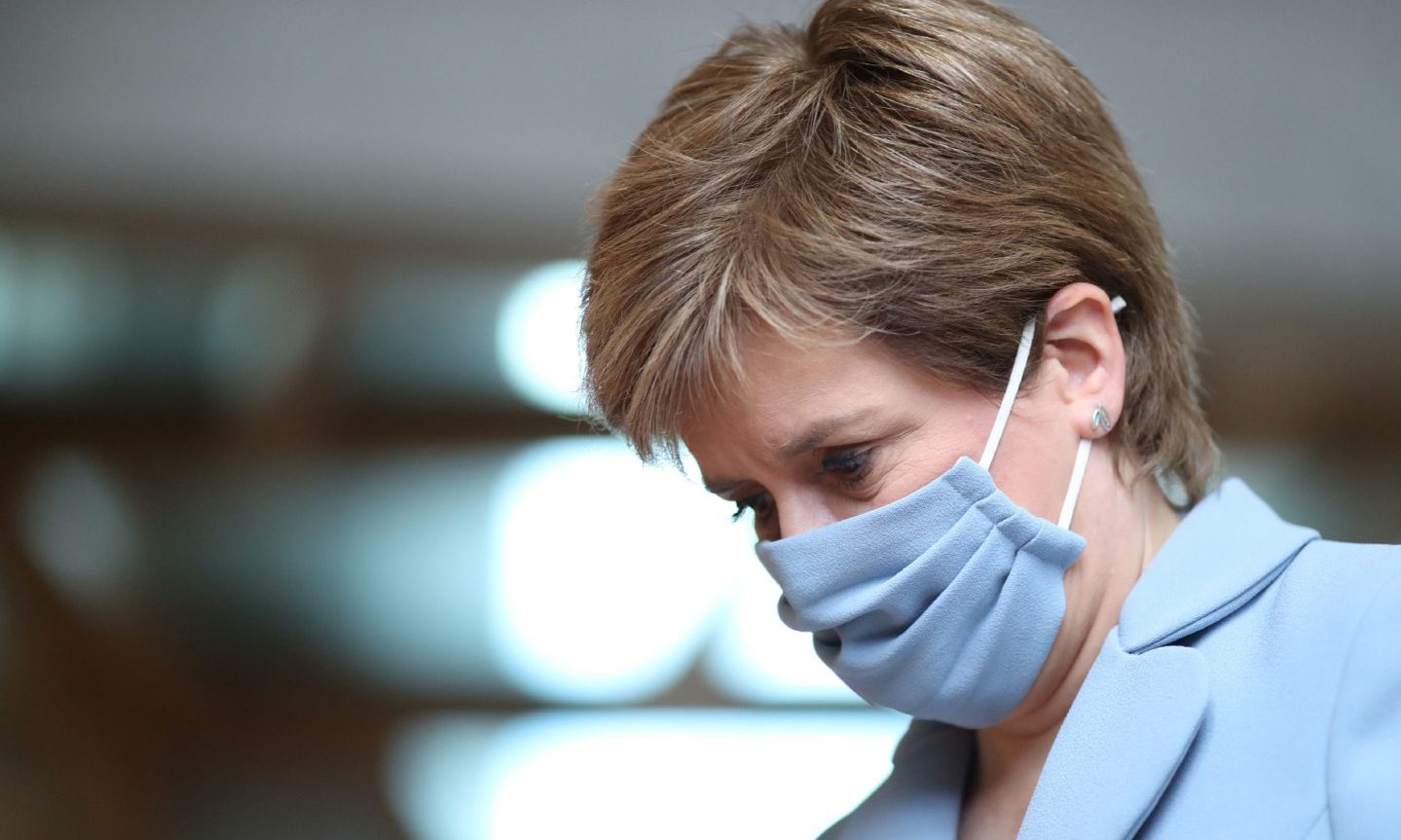

In the past couple of years Nicola Sturgeon has traversed a treacherous political mountain range.

From the Covid crisis to educational near-meltdown to the Alex Salmond saga and beyond, each icy peak has been a formidable challenge to her skills of leadership and endurance.

But the highest summit yet lies ahead and, I’m afraid, it looks increasingly likely that it will be the one to defeat her. Despite having promised her party and the wider Yes movement that there will be a second independence referendum in this parliament, she isn’t going to deliver. There won’t be a vote. There won’t be a famous victory. Scotland will continue as part of the United Kingdom.

Scotland will have a velvet divorce or none

What other outcome is there? Try to plot the path to a referendum on Sturgeon’s timescale. The Westminster government has and will continue to say no, and that no has real legal weight. The Scottish government may take to the courts, but it will almost certainly lose. Anyway, the prospect of confrontational lawfare will hardly woo those who are nervous but perhaps persuadable on the independence question.

The first minister has repeatedly ruled out the prospect of a wildcat referendum, and for good reason – the unionist parties would not take part, many unionist voters would boycott it, and the result wouldn’t be worth the paper it was written on. This would also mark a fundamental change to the campaign for independence, which has always been lawful, democratic and conciliatory. Scotland will have a velvet divorce or none.

The reality is that the SNP’s failure to win an overall majority in May – a difficult ask, but nevertheless a relevant one – has becalmed the movement. As it did in 2011, leading to the 2014 referendum, such an achievement would have conferred moral authority. Without this, there is merely argument and assertion, and this is the territory of political debate rather than indisputable democratic mandate.

Voters are neither daft nor naïve

It is true that the current UK government is of a particularly noxious breed. The arrogance of Matt Hancock – the spraying around of Covid contracts to friends and family, the weird non-apology for his double-family-wrecking affair – is only the most recent example. Throughout lockdown the cabinet behaved like schoolchildren, relentlessly briefing against one another for political advantage, blithely breaking their own rules, under a prime minister who seems to lack anything resembling moral fibre. The prospect of escaping the rule of this grim crew is, of course, enticing.

But the voters are neither daft nor naïve. They know that governments come and go, and that there is a great deal of ruin in a country. They can see that the reign of Donald Trump – a sickening and alarming episode in Western politics – is now vanishing in the rear-view mirror. Things change. Boris Johnson is hardly a stable presence. At some point Labour will return to Number 10.

At the height of her power, on the issue that most matters to her, the first minister finds herself almost entirely powerless

In the meantime, they might look at the SNP’s record in government these past 14 years and wonder what has been achieved. The schools have got worse, and the economy no better. There has been almost no significant reform of public services – the party has at all times bowed before the trade unions and the vested interests. There’s a lot of talk, but ministers have been missing in action. Hardly a promising prospectus.

Could Sturgeon stage a referendum in a year?

There are rumours that Johnson will scrap the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, which ensures general elections are held every five years, and go to the country early – perhaps in spring 2023. This gives Sturgeon just over a year to stage her referendum. Is the SNP ready? Has the case for separation – economic, constitutional, international – been effectively restructured since 2014? Have the hard questions been answered? Is there certainty anywhere to be found?

More importantly, is the electorate ready? The polls suggest not. Most Scots consider a referendum feasible on a longer timescale, but this can often seem like little more than a permanent delaying tactic. It hardly feels like Scotland – emerging from Covid, worried about its job, its family, its future – is gagging for this fight. Professor Sir John Curtice talks of “a cooling of the independence ardour”.

This is where Sturgeon sits. The legalities, the politics and the polls are largely against her. The tough-guy factions of her own movement are starting to spit and fizz at her reticence – they are aware that the door is closing and there’s no obvious way through it. But what option does she have?

At the height of her power, on the issue that most matters to her, the first minister finds herself almost entirely powerless.

Chris Deerin is a leading journalist and commentator who heads independent, non-party think tank Reform Scotland