A nation is a complex piece of machinery, a clanking wonder of ancient, rusted cogs, shining new pistons and the hum of a vast, disputatious imagination.

It is both geographical fact and philosophical idea, a haphazardly glommed-together accident of history, laws, customs, language, politics, war and people.

It is a bedtime story too, told to its children in judiciously edited form, but also a courtroom drama in which the prosecution must always assert and exaggerate difference, eternally restating the case for what makes us us and them them.

We are tolerant, open and caring, they are greedy, arrogant, warmongers. We drink and laugh and sing and win awards for our friendliness, they invade foreign town squares, throw chairs at terrified bar owners (and, for some reason, each other), and have the word “Chelsea” inked across their enormous bellies and “mum” above their shrunken hearts.

If war is the continuation of politics by other means, football is a modern diversion of both. It is for too many a circumscribed cauldron of male rage, xenophobia and racism, a zero-sum struggle for physical and intellectual supremacy, a battlefield where, if you’re a tubby skinhead with an otherwise disappointing life, you can unleash your hate without getting hurt.

English football is one of the last bastions of overt racism

But I’ve already slipped into lazy caricature, haven’t I? The vast majority of England fans, like the vast majority of the English nation, are decent, warm-hearted people who, as Sting sang of the inscrutable Russians, love their children too. They are in fact inseparable in daily life and habit from the vast majority of Scots with whom they share this small rock, with only our differing deployment of consonants and vowels sometimes giving the game away.

It is hard to avoid the conclusion that England has taken a wrong turn into a dark and dangerous place

And yet I found it a challenge during these Euros to support the England team. This both confuses and saddens me. In my civvies I’m a Manchester United fan, and many of my footballing heroes have worn the red of United and the white of England – Bobby Charlton and Bryan Robson, David Beckham and Paul Scholes and Wayne Rooney, and now Marcus Rashford, Harry Maguire and Luke Shaw. Unless they’re playing Scotland, supporting England has come as naturally as breathing to me.

This England squad, too, is a beautiful thing, in its diversity, in its moral courage facing up to racism and child poverty, in the life stories and social consciences of many of its players, in the obvious empathy and character of the extraordinary Gareth Southgate.

But it has sat uneasily on the scarred hide of Brexit England. English football is one of the last bastions of overt racism in this country, as was seen in the booing of the players as they took the knee before each match; as was seen on Sunday night when the three young, black players who missed their penalties were subjected to the most appalling abuse on social media.

The empty vessel that is Boris Johnson rode this tiger to secure Brexit and his entry to No 10, an amoral Faragiste campaign that legitimised and then cultivated the wilder fringes of boorish nationalism. It has culminated in nul points at Eurovision, and in Tory MP Lee Anderson preposterously refusing to watch the matches because of the knee thing, but also in rhetorical and physical violence, and deep, deep shame. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that England has taken a wrong turn into a dark and dangerous place.

‘English’ isn’t the same as ‘British’

When it came to the final, I found myself supporting these brilliant young men anyway, half hoping that victory might lance the ugly, swelling boil of racism and xenophobia, that it might bring an unavoidable appreciation of talent and effort, of common humanity, even of the visible benefits of immigration. It was not to be, and every unforgivable tweet feels like another nail in the coffin of a viable United Kingdom.

England lacks the space to mature, and has evolved into a sullen teenage cartoon of itself

A lot is changing in our society – progress towards racial and sexual equality, for example – and perhaps this has something to do with the insecurity of white English nationalism. It certainly lacks a depressurised democratic route in which it can be more safely controlled.

Scottish nationalism has plenty of headbangers around its edges, and anti-Englishness is rarely hard to find, but the movement has been harnessed and diverted through a democratic path. It has the opportunity to govern and to act on its beliefs. Its supporters got their referendum, and lost it.

There is an English identity, and it is not the same thing as a British identity. It lacks the space to mature, and has evolved into a sullen teenage cartoon of itself. There must, surely, be a way for wee England to grow up.

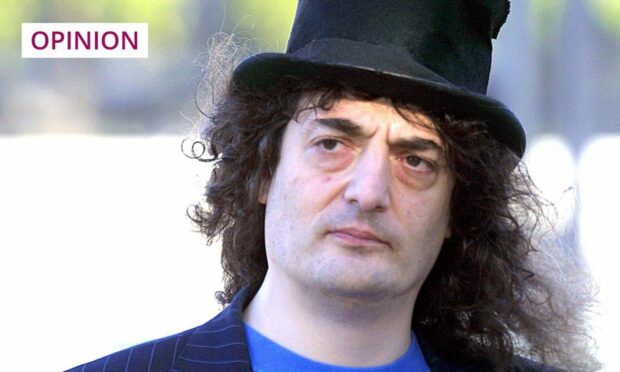

Chris Deerin is a leading journalist and commentator who heads independent, non-party think tank, Reform Scotland