Martin Sheen’s influence on foreign policy should not be underestimated. Those of us who remember him best from Vietnam epic Apocalypse Now are aware of the limits of US power and the darker impulses of human nature.

Trouble is, most of those working in the UK Government these days know him as President Jed Bartlet from The West Wing.

The snappy US drama series cast a spell on Westminster, leading them to believe it was a template for politics rather than a fairytale about America. Ever since, British politicians and, most pertinently, their young advisers have prioritised drama and unrealistic idealism over policy and pragmatism.

The West Wing is an example of the power that cultural juggernauts can have. It’s called soft power. And it’s a maxim of foreign policy wonks in Whitehall that the UK is a soft power superpower.

What is soft power?

Hard power means pointing a nuke at another nation to make them bend to your will. Invariably effective but obviously not ideal.

The UK has been kidding itself that it could trade in the global reach it achieved a century ago with dreadnoughts for something similar via Harry Potter. That’s magical thinking

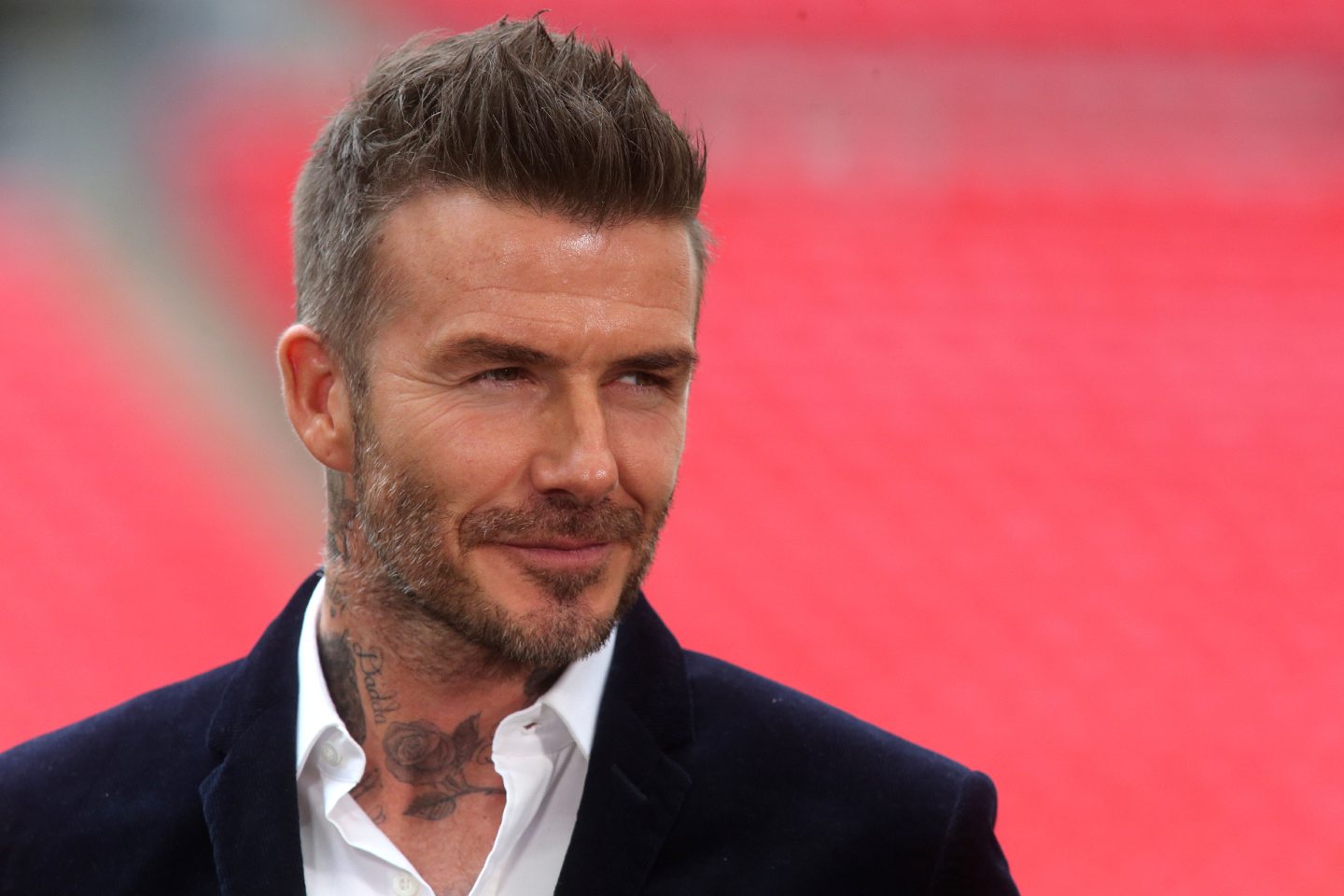

Soft power involves projecting an image that others warm to. It’s why British ambassadors have previously been urged to plaster their embassies with examples of royalty, whether that be the actual Windsors or globally recognised brands like Beckham or Bond.

It means that most folk on the planet can recognise the Union Jack – many because it has flown over their capital in the last century or so – or hum along to Love Me Do and the theme tune to Doctor Who.

But the goings on in Afghanistan over the last few days and weeks have shown up soft power for the mirage it is. The velvet glove of many a period drama has been whipped off to reveal not an iron fist but a withered finger, pointing at Joe Biden in an effort to distract from its own feeble condition.

Knowing the plot to any number of episodes of Midsomer Murders is a fat lot of use in the face of the weapons-grade dafties who have retaken control in Kabul.

The folk flocking to Kabul airport need delivery from evil, not an imported episode of Postman Pat: Special Delivery Service.

Politicians need to get their priorities straight

Defence Secretary Ben Wallace has given the impression that he understands this. His job means he’s always going to make the case for more hard power – boots on the ground, ships at sea, planes in the sky, and so on. But in his many recent media turns, he’s come across as a man capable of empathy and properly controlled emotion.

Perhaps it’s his previous employment in the military, perhaps it’s his experience as a member of the Scottish Parliament before he went to Westminster, but he appears to comprehend conflict, its human consequences and the desire to escape it.

Contrast that with Dominic Raab at the Foreign Office. Widely regarded in Westminster as a weirdo, he finally cracked appearing human by choosing to holiday in Crete rather than return to the office, something everyone can understand.

Personally, I’m broadly in favour of ministers having a summer holiday – we ought to expect public service from politicians, not total sacrifice of family life. However, that principle is overridden by the fact that I’m more in favour of stopping the Taliban, who are hideous and hateful and unequivocally bad news. Raab appears to have got his priorities tragically confused.

It’s worth noting that one of his increasingly feeble excuses was that the prime minister said he could stay on holiday. Whether that’s true or not, it’s fascinating that Raab thinks it’s plausible, such is Boris Johnson’s reputation for sloth.

The UK is kidding itself about its influence

But, despite Raab’s error, he’s unlikely to be reshuffled soon. Partly because Tory party conference is round the corner. Partly because there’s no evidence that Johnson is bothered by how his cabinet actually perform.

And all the while, China continues its “belt and road” initiative: pouring funds into countries from Mongolia to Mozambique that need a helping hand, building ports and roads and bridges, but often retaining ownership, leaving foreign leaders in hock to Beijing.

Soft power has value. But to promote and prioritise it ahead of tangible assets like people, cash and kit is soft thinking

They’re not trying to sell the Chinese equivalent of Peppa Pig into the third world. They are buying influence with hard cash, not soft power.

The UK has been kidding itself that it could trade in the global reach it achieved a century ago with dreadnoughts for something similar via Harry Potter. That’s magical thinking.

Soft power has value. But to promote and prioritise it ahead of tangible assets like people, cash and kit is soft thinking.

James Millar is a political commentator and author and a former Westminster correspondent for The Sunday Post