Somewhere in the attic of my primary school was an instrument of terrible purpose.

It would lie dormant for months at a time but, like a sleeping dragon, when awakened would spit fire.

Such was its awesome power, you could be anywhere in town and still suffer its wrath: a slow, sickly wailing, gradually gaining in amplitude and speed. It was pitched at the level of nightmares, promising death and destruction and an end to things. Though it was the early 1980s, older people must have checked the sky for the Luftwaffe.

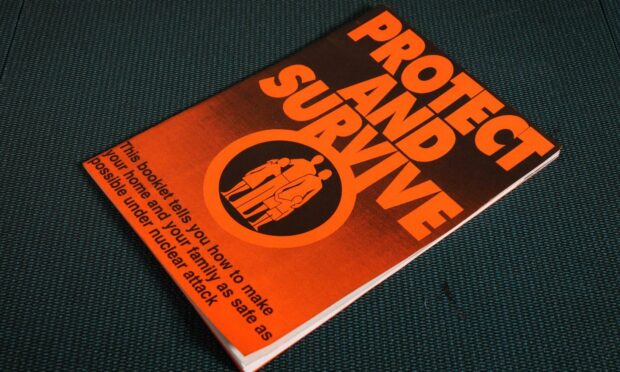

Pah to your Hitler and his massed ranks. Like much else in the eighties, annihilation had become smaller and more efficient. This was the siren that would sound in the event of a nuclear attack, giving us the briefest of warnings that Mr Brezhnev or Mr Andropov had tired of us and was about to deliver our extinction. It was said to be hand-cranked by the school janitor: old, bespectacled Mr Boyle in his crumpled blue overalls and Doc Martens – an unlikely messenger of doom.

Today’s kids have a new version of planetary terror

At this distance, I wonder whether it was true – not the Soviet menace, but the reality of the siren and those occasional tests. I mean, what if Mr Boyle couldn’t find his glasses? Regardless, it speaks of growing up in an era of ever-present existential threat, of tense diplomatic and military stand-offs, of Ronald Reagan’s genial toughness versus sinister, blank-faced Russians, of children being shown films of what to do when the Bomb finally dropped. Maybe worst of all, there was that godawful Sting song.

It all comes back so readily, doesn’t it? Duck and cover. Paint your windows white if there’s time (quick, Mary, where’s the Dulux?). Up-end your desk and hide behind it. Shut your eyes and pray. As a defence against skin-shredding, horizon-immolating, building-obliterating radiation waves, it didn’t seem much, even to a giggly, if confused and frightened, eight-year-old.

The end of the Cold War did away with all that, with the Soviets and the screenings of Threads and the low hum of nuclear anxiety, and for a while our young were allowed to flower in relative calm and siren-free safety. Sadly, the fear is back. Today’s children face their own version of planetary terror, and if anything, it’s even more real.

Eco-anxiety is growing. Around 45% of kids have been found to suffer depression after surviving extreme weather and natural disasters. Even those for whom such events remain largely theoretical or geographically distant are increasingly aware of the looming risk to their future. It’s not just Greta Thunberg who’s angry.

‘We are being sacrificed’

If you have school-age offspring of your own, you’ve probably had and are having the conversations, and struggling to answer the perfectly reasonable questions about why more isn’t being done by today’s grown-ups to head off calamity.

The basic reason for being at COP26, and the urgency with which mass and coordinated action is required, could fall victim to the juvenility of grown-up politics and its pathetic alpha-male egos

The finer points of international deal-making and compromise, of economic complexity and supply chain demands, ring hollow in the innocent face of a worried child. They know what they’re talking about, too – they are bombarded with facts and warnings and videos on social media, and they talk to each other. Very often, they have a moral clarity that we adults, with our weary pragmatism and our cognitive dissonance, simply lack.

A University of Bath study from 2019 makes difficult reading. “It’s normal for us now to grow up in a world where there will be no polar bears, that’s just how it is for us now, it’s different than it was for you,” one British child told researchers. A teenager in the Maldives, which is gradually sinking under rising sea levels, said: “We saw online that people in Iceland held a funeral for a glacier… but who is going to do that for us? Don’t they see that we will be underwater soon and our country will be gone? No one cares. We are being sacrificed.”

It’s not yet clear whether there will be a Glasgow Agreement worth the name after world leaders gather in the city in a few weeks’ time. So many competing agendas, so many ulterior motives and irrelevant beefs will be in play, that the basic reason for being there, and the urgency with which mass and coordinated action is required, could fall victim to the juvenility of grown-up politics and its pathetic alpha-male egos.

In the end, the long post-war era of threatened nuclear annihilation and mutually assured destruction was brought to an end by the hard realities of economics and power. Yet it is those realities that are preventing the necessary action on climate change. What a shameful story our children will have to tell their own.

Chris Deerin is a leading journalist and commentator who heads independent, non-party think tank Reform Scotland