There was a time when we collected famous Scots like a child gathers Easter eggs.

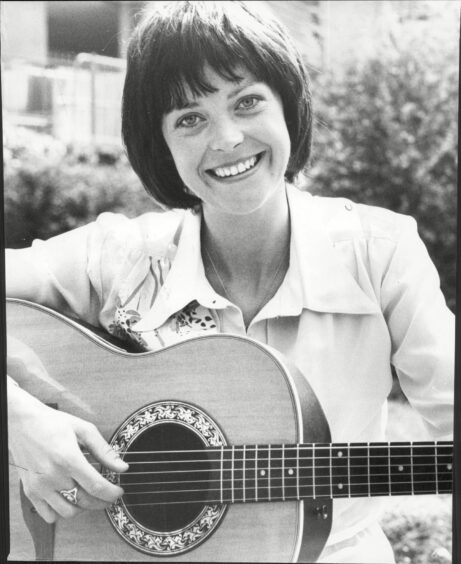

Here is Sean Connery, here Isla St Clair from the Generation Game, here the swimmer David Wilkie. An eclectic basket of success which proved our self worth.

We don’t do this any more.

The hugely successful TV programme, Succession, launches for a third season with Dundonian Brian Cox in the lead, while Cameron Norrie, the son of Scottish expats, wins at Indian Wells, but we are calmer about our success, thankfully. Not so chippy.

From the 1970s to now, we have gained in confidence.

It is an illusive concept, confidence. It underpins the global economy and social order, with no central agency or legal definition to control it. It is a huge factor in life – the confident child thrives, becomes the risk-taking adult; carries doubt as as an intellectual aid, not a crippling burden.

Scots have an ambiguous relationship with confidence.

It came up in the independence referendum, its lack being cited by nationalists as a reason for being a “feartie”.

Thankfully, you rarely hear this line of argument seven years later, because it is patronising and simplistic. It seems more likely that no voters were confident in their assessment that the big holes in the yes argument meant dragons lived in the terra incognito of independence.

Confidence gap has deep roots

A decade before 2014, Carol Craig argued that Scots lacked confidence and the greatest reason for this was nationalist rhetoric saying Westminster does us down.

You can go further back. Alasdair Gray wrote a lovely short story about a Scot coming unstuck in London, hitting a cultural nerve on the balance between confidence and cockiness.

That taps into the centuries-old tension between confidence in God or the self, as described by the Ettrick Shepherd.

The confidence issue describes Scottish antipathy to our southern neighbours. It’s not the English we dislike, but the presumptuous ones, whether public school twit or direct northerner. Which is, of course, not special to the Scots.

Yet the English, like the rest of the world, have the cultural trope of the rude Scot, certain in his or her capabilities and dismissive of discussion.

Confidence as a class issue

A new discussion about confidence in Scotland is overdue, chiefly because it remains a class issue more than an identity one.

Give me an educated, middle class Scot and I’ll give you a global standard in confidence. Assured of national identity, unflinching in the face of authority.

The less educated, less well-off are more likely to find doubt a burden, authority a threat

The well-off have gained in confidence. No longer the defensive mindset, if that was ever true, of a few decades ago but comfortable in their skin as the equal of anyone. Here, the once infamous Scottish cringe is on the decline.

For predictable and preventable reasons, the less educated, less well-off are more likely to find doubt a burden, authority a threat.

Anyone can cook up 90-minute confidence, but we still season that with foreboding. No good will come of hope.

Waiting game does not further the cause

The SNP’s Ian Blackford calls for a “new focus” on what independence can do for Scotland, while colleague Angus Robertson says it’s just a demographic waiting game before old unionists die and young nationalists win freedom.

Both betray a sense of how the purpose of independence has got lost.

It seems alarming that, after 14 years of government, the SNP is still vague on what independence is for, and quite scary that it might have become an event which happens because time passes. It does not help the endemic problems of poverty and lives blunted by disadvantage to simply wait for a day when the legal status of the government changes.

As a nationalist, I think it’s fair to say that devolution and nationalist political dominance has shifted the confidence dial, but not addressed its root causes. We haven’t fundamentally changed the quality of Scotland from its pre-devolution days.

We no longer pan for golden Scots, but we have done little to improve the lot of the ordinary citizen. It would be a more noble cause if independence was code for the betterment of Scotland today, tomorrow and at all times.

We must create the conditions for confidence

That support for the nation was won by helping the nation.

Our great well of doubt, our crippling lack of confidence, stems from straightforward economic factors.

We have too many socially excluded people, because too many households are poor. We can address this by redirecting money from universal, middle class-benefiting services towards targeted, pro-working class provision. We can do this now.

Thinking our poor will magically become confident through changes to the constitution is weak, and a political cop out

It would require the polar axis of the independence movement switching from the assertion that independence will bring confidence to the practical policies which will build confidence now, and will lead to a confident nation.

Confidence is a cornerstone of the happy life and the good society. Thinking our poor will magically become confident through changes to the constitution is weak, and a political cop out.

If nationalism is about the betterment of the nation, then the task of building confidence comes first, and last. Everything else is merely a side effect.