Both in Westminster and in Holyrood, these are frustrating times for opposition politicians who find themselves confronting governments possessed of an unprecedented capacity to ride out difficulties of a sort once reckoned to signal the imminent ejection from office of any set of ministers presiding over them.

Recent history offers a plethora of examples of administrations laid low by economic and other troubles they were thought – fairly or unfairly – to have mishandled.

The 2010 fall of Gordon Brown’s Labour government was wrapped up with its supposed inability to control public spending in the wake of the worldwide financial crisis of a couple of years earlier.

John Major’s Conservatives were ejected from office in 1997, not least because of their failure to recover from the reputational damage inflicted on them by the UK’s enforced departure from the European Union’s Exchange Rate Mechanism – a departure preceded by interest rates (today not much above zero) rising, at one point, to a dizzying 15%.

The 1979 ejection from office of Jim Callaghan’s Labour government was inextricably bound up with the Callaghan team’s botched response to the immediately preceding “winter of discontent”, when public sector strikes led to rubbish piling up in the streets and, or so it was said, to the dead being left unburied.

Now there’s talk to the effect that a new winter of discontent might be just around the corner, resulting, this time, from soaring energy prices, empty supermarket shelves, labour shortages, rising inflation, benefit cuts, ever-longer NHS waiting times, the continuing pandemic and the many other crises highlighted nightly on television news.

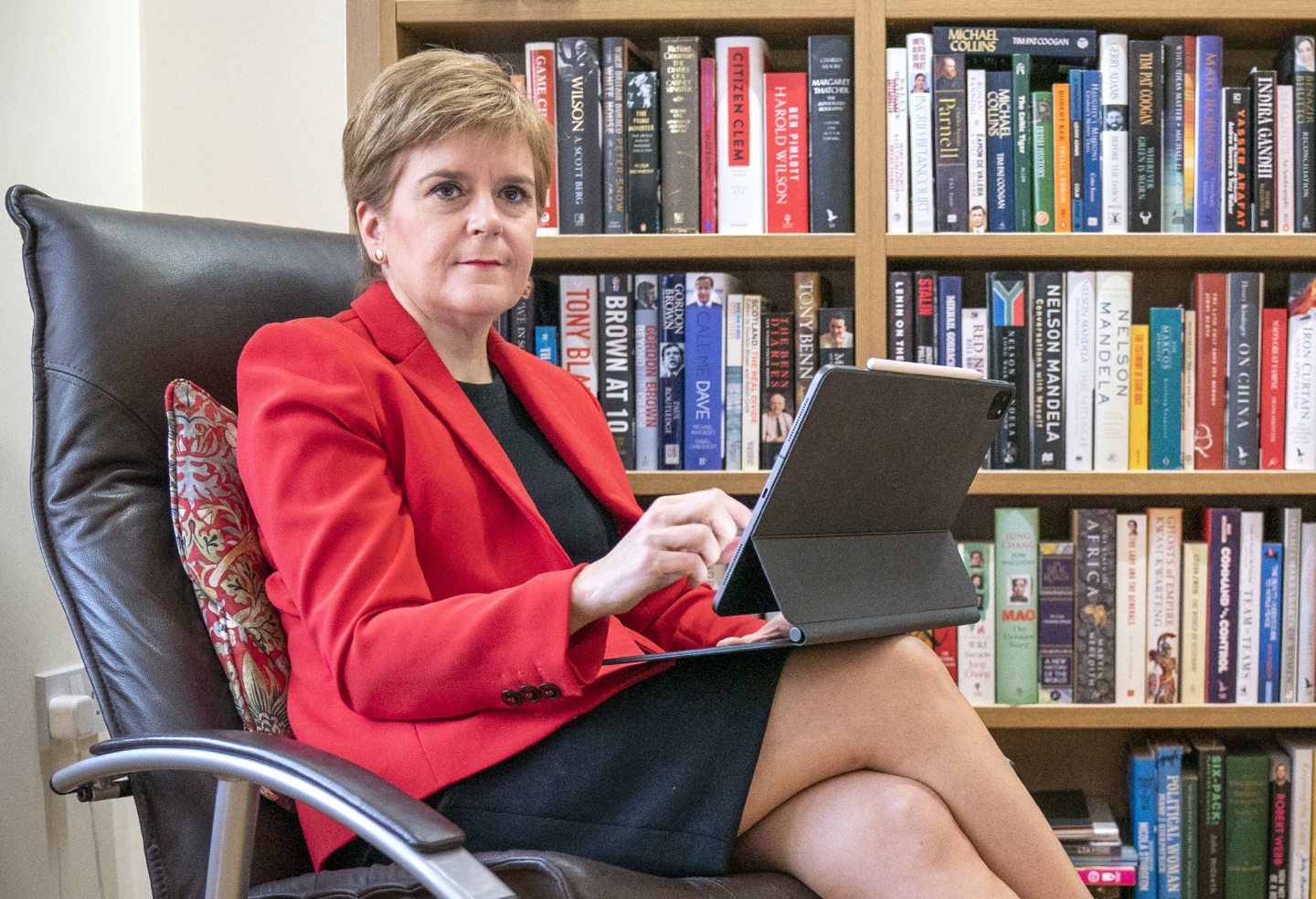

Boris Johnson and Nicola Sturgeon’s popularity isn’t waning

Experience suggests that, in response to the growing sense of a country in disarray, support for Boris Johnson’s Tories ought to be in freefall. But it isn’t. Mr Johnson remains as chipper as ever while opposition leader Keir Starmer finds it hard to gain a hearing, let alone win the widespread public backing he’ll need if he’s ever to win an election.

The way people vote has less and less to do with a government’s competence or lack of it; more and more to do with what that government is thought to stand for

North of the border, meanwhile, the SNP government, in office at Holyrood since 2007, seems equally immune to charges of failure, whether that failure has to do with getting a grip on Scotland’s drug death toll or the wholly scandalous inadequacy of Hebridean ferry services.

Why is this? Why are neither the SNP administration in Edinburgh nor its Conservative counterpart in London being more seriously menaced – scarcely being menaced at all – by opposition parties who don’t need to look far for evidence of ministerial shortcomings?

One part of the answer, surely, is the extent to which electoral politics in the UK have become bound up – in ways that, outside Northern Ireland, they’ve not been before – with issues of national identity. The way people vote has less and less to do with a government’s competence or lack of it; more and more to do with what that government is thought to stand for.

And what Boris Johnson’s government stands for is clear enough. As Mr Johnson never ceases to remind us, his is the team that “got Brexit done”, that took the UK out the EU, that restored British sovereignty and “took back control” of the country’s borders – thus stopping, or drastically curtailing, immigration into the UK from the rest of Europe while simultaneously fostering the emergence of an allegedly unbound “Global Britain“.

Will any future failures stick?

In England in particular, and among England’s anti-EU majority even more so, this results (or has resulted so far, anyway) in the Conservative Party being seen as the embodiment, in some sense, of the resurgent national feeling – the English nationalism, if you like – that lay behind the 2016 Brexit vote and went on to deliver to the Tories the so-called “red wall” constituencies lost by Labour in 2019.

And what’s true of England is equally true of Scotland – with the key difference that our nationalist upsurge is directed not at getting Britain out of Europe, but getting Scotland out of the UK.

So, just as England’s pro-Brexit voters are prepared, for the moment at least, to go on throwing their weight behind Brexit’s Tory deliverers, so the half of the Scottish electorate who favour independence are in no way inclined to abandon Nicola Sturgeon’s SNP.

This may change. Older patterns may assert themselves. Opposition claims – well-founded claims, in many instances – of governmental bungling and mismanagement may become once more the vote-winning charges they were in the past. But opposition efforts notwithstanding, there’s so far precious little sign of this.

Jim Hunter is a historian, award-winning author and Emeritus Professor of History at the University of the Highlands and Islands