When I was a law student, back in the last century, I spent a summer working in a solicitors’ office in Inverness.

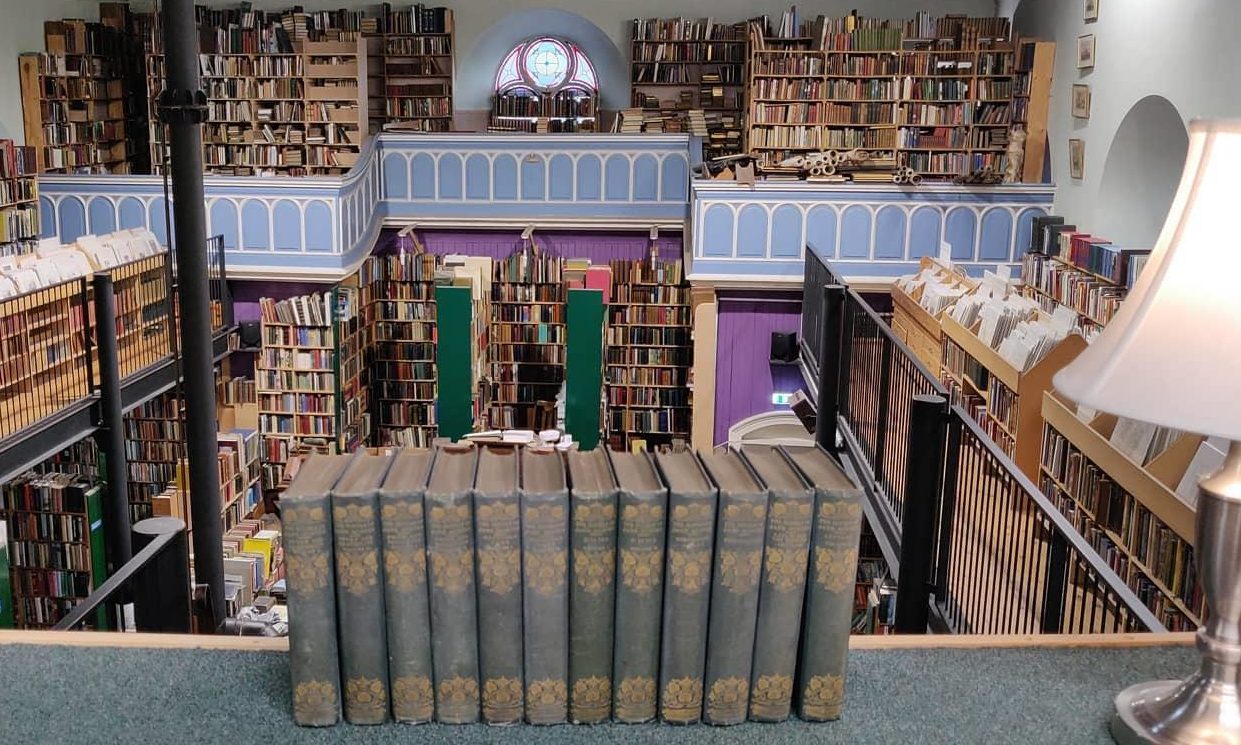

Each Thursday, which was pay day, I’d browse in Melven’s Bookshop and purchase a Penguin Classic paperback.

I wrote my name and the date on the inside cover and enjoyed watching my fledgling collection grow. The books are with me now – Charles Dickens (never really got him), Anne and Charlotte Brontë, Rudyard Kipling, EM Forster, Henry James, Oscar Wilde, Thomas Hardy, George Eliot, Jane Austen and others. There’s even Virgil’s Aeneid and Homer’s Iliad which, who knows, I may even open one day. But I read and enjoyed almost all of them.

Maybe it sounds pretentious but, thinking back, I feel nothing but affection for that earnest young woman who only wanted to read good books. To be honest, she’s still here.

Books offered a respite from grim reality

The book-buying habit continued over the decades. All sorts of stuff: heavyweight, lightweight, worthy, funny, baffling, terrible, terrifying – just like life itself, really. Now I have an upstairs room which is wall-to-wall fiction. In my head I call it the library, though it’s really just the spare bedroom.

Now, fast forward to the pandemic where, as for many of us, my world became small and domestic and hasn’t really recovered. Prior to Covid, my book-buying habit had slowed thanks to the addictive, bite-sized charms of the internet. But, in the stillness of lockdown, I felt the urge to revisit my old paperback friends.

Perhaps it had something to do with spending so much time cooped up within the same four walls as them but, also, once I began reading again, I discovered that books were the only things which offered a genuine respite from grim news across the world.

Films and telly are great, but there’s nothing like the gripping escapism of getting stuck into a Really Good Book. Lamplit late nights, then that longing to pick up the story again first thing next morning. And, of course, the slowing down as the end nears because it feels too soon to say goodbye.

Revisiting Auntie Jane

My impulse was to re-read my favourites first, so I reached for Thomas Hardy. I used to love his strong, feisty heroines and the earthy richness of their trials and misfortunes. But as I reached for him, I hesitated. I couldn’t bear to relive the terrible happenings visited upon his characters.

Remembering the note left by Little Father Time in Jude the Obscure, after he killed himself and his siblings: “Done because we are too menny”, I was assailed by pangs of dread at the very idea of going through all that again. And poor Tess Durbeyfield, calmly asking: “Have they come for me?” on the day of her execution. Nope, nope, nope. I couldn’t do it.

I was thrilled when I discovered that my husband counts none other than Jane Austen herself in his family tree, on his mum’s side

It’s one thing to be touched by a book but quite another to be wounded by it. Perhaps, in lockdown, I’ve gone soft.

Craving a less turbulent flight from reality, I settled on Jane Austen, retreating into worlds of bonnets, parsonages and relentless pursuits of suitable husbands.

Oh! Speaking of suitable husbands, I was thrilled when I discovered that mine counts none other than Jane Austen herself in his family tree, on his mum’s side. Not directly, as Austen died unmarried and childless, but she’s there nonetheless: his many-times-over great aunt.

As claims to fame go, it’s pretty tenuous, but here I am, milking it anyway. Auntie Jane would not have approved such indelicacy.

Retreating into the past to prepare for the future

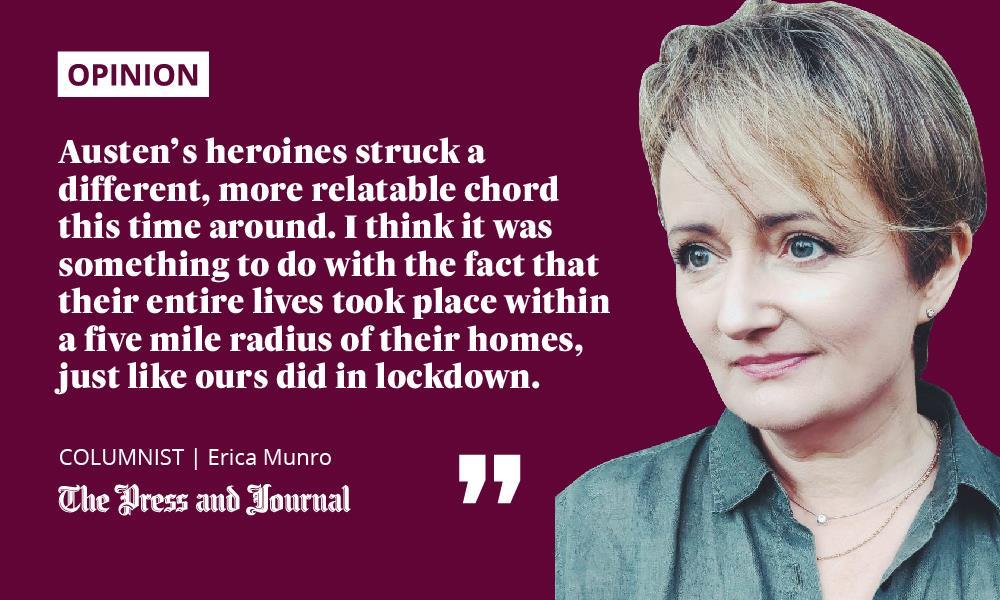

But, I digress. Austen’s heroines struck a different, more relatable chord this time around. I think it was something to do with the fact that their entire lives took place within a five mile radius of their homes, just like ours did in lockdown. Emma Woodhouse meddled in matchmaking because she wanted her friend to be happy.

Lizzie Bennet put up with all that nonsense from her family because she loved them and wanted them to be safe. Fanny Price was an insufferable killjoy, but at least she was thoughtful and remembered her manners. And so on.

They were privileged, but in the midst of that, they had few worldly distractions and meant well. They were untravelled, as were we, but they made the best of it. They called on their neighbours. They worried about offending their friends.

With COP26 ongoing and the climate emergency finally being acknowledged, I question why I retreated into the past, when all the talk is of the future. But, maybe, somewhere in Auntie Jane’s world, there’s a whisper of guidance.

Erica Munro is a novelist, playwright, screenwriter and freelance editor