When it comes to filthy lucre, how dirty does it have to be before you have the moral responsibility to refuse it?

That is the dilemma facing Oxford University, which has been accused of “moral failure” by Oxford professor, Lawrence Goldman.

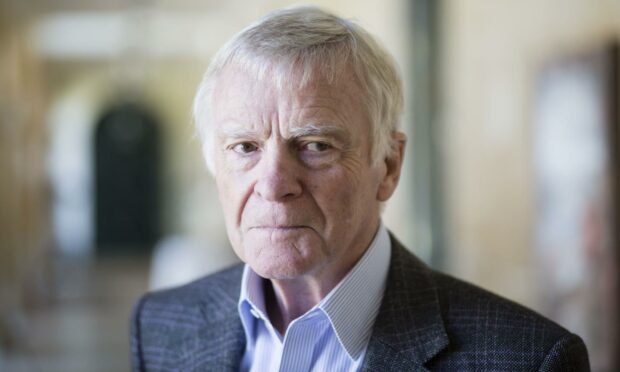

Goldman is protesting that the university accepted £6.3 million from a charitable trust established by Max Mosley, whose fortune was partly founded on the wealth of his father, Sir Oswald Mosley, the notorious leader of the British Union of Fascists.

How do you launder that kind of money to make it smell sweeter? I’d say that the donor dying is a start.

Oswald Mosley died in 1980; Max Mosley in May this year. Like his father, Max Mosley had a less than salubrious past in so many ways, but one of the good things he did in his life was use some of his wealth to establish a charitable trust.

He was motivated by personal tragedy: the loss of his son, Alexander, who attended Oxford and died from a drug overdose. It’s an event that would break most parents, and in suffering there is transformation.

Mosley was privileged to have millions to make Alexander’s memory live on – and therein lies an important point. It is Alexander Mosley’s name that is associated with the biophysics professorship established by the trust. Not Oswald Mosley. Not Max Mosley. Are we really saying you are your family name?

How long does money stay tainted?

The notion that a family passes on its sins to those who weren’t around when they were committed came up this week in another context: a story about the stepdaughter of an IRA sympathiser being cast as Lady Mountbatten in a new series of The Crown.

Apparently, it was “insensitive” to cast Natascha McElhone. But what’s it got to do with her what her stepfather believes? Why should it disadvantage her as an actress? We’re not even talking genes here, just connections.

Morally challenging questions usually have two sides that would be easy to support. That’s what makes them challenging.

I have sympathy with Professor Goldman, who had family murdered by the Nazis, especially when a poll this week showed half of Britons do not know that six million people died in the holocaust. But should the past override the ability to do good when everyone connected to tainted money has shuffled off this mortal coil?

Five million pounds will be spent building student accommodation. It will not have the Mosley name attached. Instead, students will choose a name.

Why not use this money to benefit all the causes that fascism opposed? Bursaries for Jewish students. Grants for the underprivileged and for ethnic minorities.

“Its moral compass is just not working anymore,” Goldman said of the university. Well, that’s been true for generations when it comes to elitism.

Oxford, which has consistently been named the number one university in the UK, and has recently been awarded the number two spot among world universities, likes to boast that its state school entrants now make up 69% of its intake. That means 31% are still privately educated – despite only 6% of the population going to private school. Go figure, as the Americans would say.

Use dubious funds for a good cause

Like seized Jewish art treasures rightfully restored, this money should be taken back for good causes.

If the money from the Mosleys’ charitable trust was to publicise fascism, or was derived from ongoing wrongdoing, I would protest. It is not

Use it to tear down the elite structures that fascism upheld and open up Oxford. Use it to promote the groups they oppressed. Use it to make Oxford university accessible to the disadvantaged and the dispossessed – those without wealthy families to support them the way Alexander Mosley’s did. Poor little rich boy. There is nothing to fear any more from him or his ancestors.

The desire to use money currently for good causes outweighs its dubious past.

In George Bernard Shaw’s play, Major Barbara, a young idealistic Salvation Army volunteer is morally challenged when her estranged father, who owns a munitions factory, wants to donate money. Shaw’s view was that poverty trumped everything else.

“In your Salvation shelter I saw poverty, misery, cold and hunger,” Barbara’s father tells her. “You gave them bread and treacle and dreams of heaven. I give from 30 shillings a week to 12,000 a year.”

Barbara’s father continued to make his money from weapons, which perhaps makes his donation more morally questionable. But that isn’t the case at Oxford.

The famous Mosleys are gone. If the money from their charitable trust was to publicise fascism, or was derived from ongoing wrongdoing, I would protest. It is not. And it seems to me that the only way to properly launder the dirty money of the dead is to use it for the good causes of the living.

Catherine Deveney is an award-winning investigative journalist, novelist and television presenter