Birds of a feather flock together.

Commonly meaning that like hangs out with like – mods with mods (remember them?), rockers with rockers, Dons supporters with Dons supporters, and so on.

I believe social media refer to people living in cocooned silos when it comes to the echo chamber of the internet, where folk follow and read only those they agree with, so that any different, diverse point of view is never heard or considered.

But there are feathers and feathers. When I look out the window, I see almost a whole universe of birds in my garden. Robins and wrens and goldfinches and greenfinches and sparrows and blackbirds and blue tits and collared doves and siskins and bullfinches and chaffinches. And the occasional seagull.

They are all feathered birds, of course, but as different from one another as Brechin City’s stadium is from the Bernabéu, even though football happens at both.

A nation which made became a nation which consumes

I wasn’t really going to write about birds at all, but about industrial estates, so I’d better explain myself. I find myself hanging about industrial estates far too often, trying to get my car fixed at a garage, so while the magician mechanic investigates the existential meaning of the engine, I go for a wander. And I like what I see.

A blacksmith working in one shed and a sandwich maker in the next. A welder flying sparks in one hut and a fish processing unit in the next. Like a robin pecking at the seed in one of my garden feeders and a sparrow in the other one. And, when I walk through these industrial estates, I become convinced that the very heart of the working world beats there.

Not in the great factories which drove the Industrial Revolution, but in the smaller units which keep the show on the road. Our economy, of course, needs the great drivers of jobs and wealth and industry – the oil rigs decorating the North Sea (in the meantime anyway!), the distilleries peppering our glens, the wind turbines adorning our hills and seas, the factories that still manufacture products, ranging from the massive John Wood Group to smaller but hugely important makers, such as the battery making Denchi Group in Thurso.

The world became a village, and things could be bought cheaper from China than they could be made here

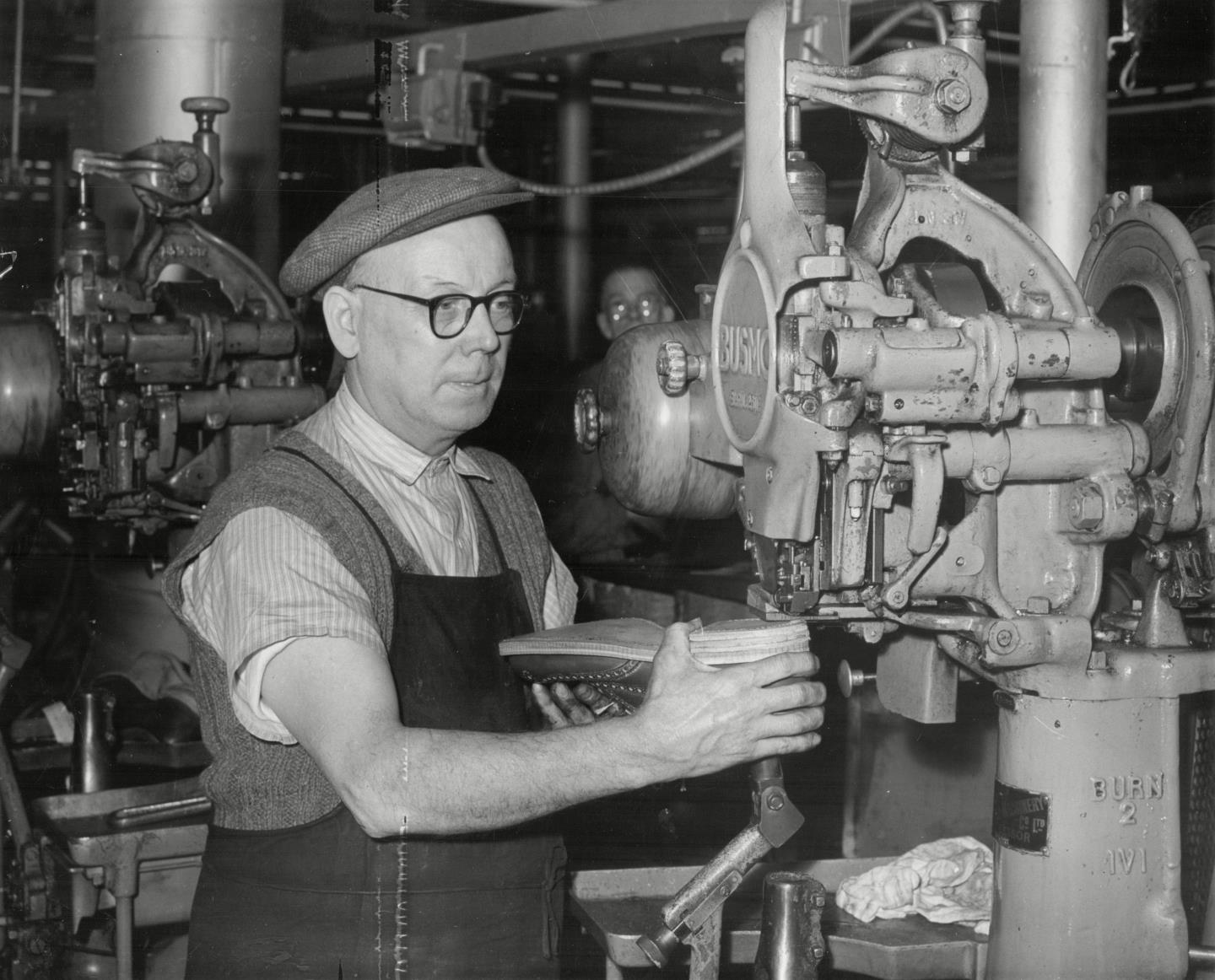

The loss of our world-renowned manufacturing base in Scotland over the past 40 years or so has been cataclysmic. No wonder the Proclaimers sang “Bathgate no more, Linwood no more, Methil no more, Irvine no more…”

At its height in the 1960s, Singer in Clydebank employed over 12,000. In the late 1970s, over 3,000 worked at the Kishorn fabrication yard in Wester Ross, and another thousand at the Invergordon smelter. Hundreds of thousands of jobs have disappeared as we made the sorry transfer from being a nation that made things to a nation that merely consumes them. Like gulls hovering over cold chips.

Tradespeople and artists are birds of a feather

We understand why – the world became a village, and things could be bought cheaper from China than they could be made here, thanks (mostly) to lower wages over there and fewer health and safety requirements. But that’s only part of the story: we have failed ourselves. Failed to retrain our young people, failed to fuel technical education, failed to support risk-taking and venture-taking, and failed to take proper advantage of the natural resources of wind and waves and land that we have. Failed to be adventurous and creative.

But I have a dream. That one day art and craft will work hand in hand again. For art is craft and craft is art. At the moment, when I walk through an industrial site I see garages and blacksmiths and joiners and stonemasons and fish merchants and sandwich makers working next door to each other, while in another, separate part of town, artists (if they’re extremely lucky) have their own little workshops and galleries.

They should be working side by side, learning from and strengthening each other. I want to see business parks and industrial estates designed and marketed (with low rents for poor artists) so that, while your car is getting fixed, you can go to the shed next door to watch a luthier at work or see a piper making reeds or an accordionist play her latest tune. I’d definitely buy a CD while waiting for that carburettor to be fixed.

I’m a writer, not a welder, though it’s basically the same trade: taking broken things and repairing them, fusing a world together. We could be like the geese, flying together in a perfect, sustainable V formation, flying south for the winter fields, north for the summer pastures.

Angus Peter Campbell is an award-winning writer and actor from Uist