There are many wonderful tennis matches for which Rafael Nadal will ultimately be remembered, but let’s concentrate on just two.

The first is the 2008 Wimbledon final, generally regarded as the greatest of all time. Nadal was, as so often in his career, the less-favoured competitor. His opponent, Roger Federer, was at his majestic height, and had beaten Nadal in the previous two centre court finals. But, over five hours, the Spaniard’s physical and psychological refusal to accept defeat finally wore the brilliant Swiss player down, even if at times it seemed like the match might simply continue forever. He won three sets to two. He was 22.

The second is Sunday’s extraordinary final of the Australian Open where, having gone down two sets to love, Nadal dug as deep as any sports star ever has to somehow claw his way back to win. It took five hours and 24 minutes of relentless, white-knuckle effort for him to turn the tide against Russia’s more-fancied Daniil Medvedev. Medvedev is 25, in the prime of his career. Nadal is 35, the kind of age where your bones and muscles have begun mercilessly paying you back for decades of strain and abuse.

A lot can be learned in 14 years

It pays to compare photos from the two eras. In the first, Covid had never been heard of and the tournament hadn’t been overshadowed by Novak Djokovic’s refusal to get vaccinated. Andy Roddick and Lleyton Hewitt were still playing, perhaps not yet realising they’d been left behind by a new age of genius. In the latter, there is general amazement that Nadal and Federer are still somehow able to strap their beleaguered bodies into place and limp onto a court, never mind still be winning.

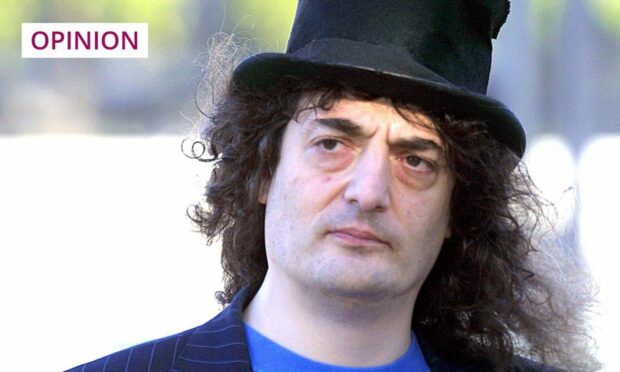

You can see the difference in Nadal, too. At Wimbledon he’s very much the tennis hunk – the surfer’s long hair, the smooth, bronzed Mallorcan skin, the sleeveless vest to display those iconic, brand-enhancing arms, knee-length shorts suggesting he’s left his skateboard at courtside. At Melbourne Park, anything that might nod to fashion has been cast aside. The hair is neatly chopped, the shorts come to conservative mid-thigh, and he is wearing a plain purple top (with sleeves). The skin is tauter and shows signs of sun damage.

Are the true greats ever greater than they are towards the end? When their career is approaching heat death and they are often running on muscle memory?

The difference between a young man and (in sporting terms) and an old one. By now, all that matters to Nadal is victory. The drive burns as brightly as ever, but the fripperies have been discarded. The money is already made, as is the legend. Efficiency is all. Energy must not be wasted. The record for the most ever grand slams by a male tennis player is there for the taking. And, at the back of it all, there is awareness that the final, burning horizon is now close.

Are the true greats ever greater than they are towards the end? When their career is approaching heat death and they are often running on muscle memory, experience, a raging against the dying of the light that is accompanied by an indefinable grace?

We and what we do are time-limited

One of the books I’m most looking forward to this year is the latest from Geoff Dyer, one of the most iconoclastic and interesting writers of our times. In The Last Days of Roger Federer: And Other Endings, Dyer examines the last works of writers, painters, sports stars, philosophers and musicians. He explores Bob Dylan’s reinventions of old songs, Turner’s paintings of abstracted light, John Coltrane’s cosmic melodies, Björn Borg’s defeats, Beethoven’s final quartets. He “considers the intensifications and modifications of experience that come when an ending is within sight,” says Canongate, his publisher.

This is a perfect work for me. I’ve always been fascinated by the late periods of the best artists – what emerges when they’ve bust through the other side of youthful, hormonal fury, when they know one piano note can be better than 10, or a simple sentence hold more power than a florid paragraph, when an unexpected line shot can leave a 20-something prodigy on his backside.

I, like Dyer it seems, am always brought back to Beethoven and those last quartets; works of divine beauty and mystery, parts of them still impenetrable, awaiting the insights of future ages. As with Nadal, the garnishing is gone, replaced by a deeper connection to the unseeable sublime.

We all have our own version of this as we age and put away childish things. We recognise that we and what we do are time-limited, and that any imprint we might leave on the world’s surface will require the weight of authenticity if it is to outlast us. Only connect, the poet said, and in time we come to learn he was right.

Chris Deerin is a leading journalist and commentator who heads independent, non-party think tank, Reform Scotland